3 Reasons Why You Should Watch Lucky Hank

And why AMC's comedy is better than Netflix's The Chair

First, a little housekeeping: Last month, while writing about Lucy Gayheart, I thought it might be fun to organize a virtual book club for readers of this series. The response to my informal poll was encouraging, so I’d like to save Thursday, August 10, from 7:30-9:00 p.m., EST, for our first gathering. To streamline things, I’ll propose four titles for our first meeting and ask for your preferences here. I’ve been so grateful for your contributions in the comments and in our Friday threads each week, and I’m excited about strengthening our community in this way! Stay tuned for updates and an RSVP invitation as the time approaches.

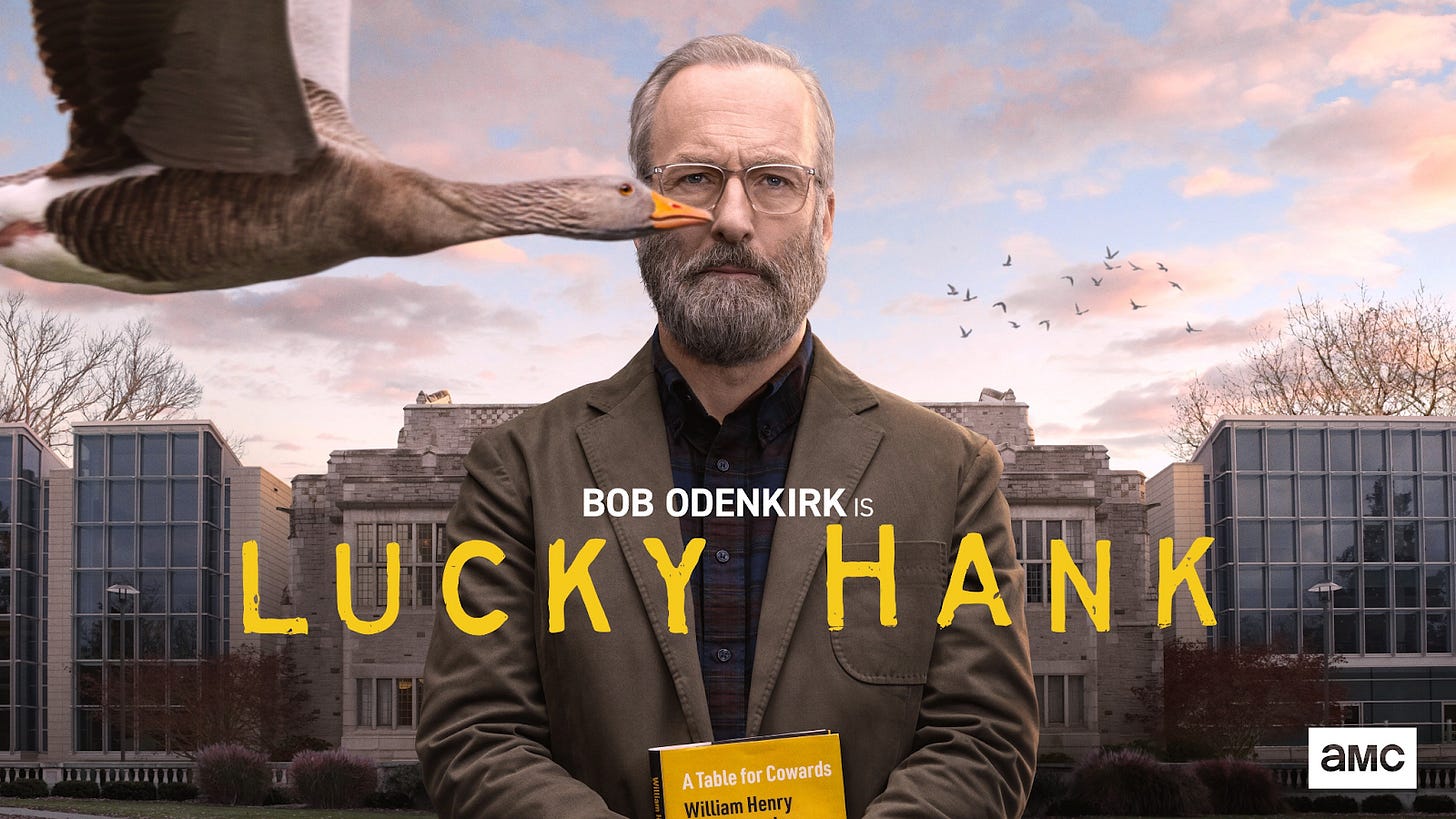

3 Reasons Why You Should Watch Lucky Hank

Several weeks ago, while I was interviewing people for a piece that may or may not end up in The Chronicle, the president of a college in New England recommended that I watch Lucky Hank. The AMC series is an adaptation of Richard Russo’s Straight Man, which parodies faculty at a small college in Pennsylvania. It’s not that Russo doesn’t strike close to the mark — he captures many absurdities that I remember well from my own days at a small liberal arts college. It’s more that Russo reinforces the stereotype of literature professors as overgrown children. You might even say that he endorses the view that humanities programs aren’t worth defending. Anyone who has seen Netflix’s series The Chair will understand what I mean. You laugh along with the story, sometimes morbidly, because you recognize the scene all too well, but at some point the heartburn kicks in, because you know that your discipline is not a joke. It’s like those personal stories that are hilarious when shared within your family or cultural group, but that land a little differently in public.

For instance, I had an experience during my first semester as a visiting assistant professor that was almost too bizarre to be believed. A senior professor whom I’ll call Carl had been nursing a grudge against another senior professor, Bob, for years. Carl approached me with a proposal that he meant to carry to the dean. He would take a part-time position if Bob did the same, thereby creating a full-time tenure-track position for me. I wanted no part of it and doubted that it would come to anything. But at the very next meeting, Carl surprised the rest of the department with copies of the memo. “Bob,” he said, “Aren’t you prepared to make a sacrifice for your friend Josh?” The argument brought the two of them to their feet, and it nearly came to blows. I fled the meeting as soon as I could, agonizing over whether Bob might think that I’d been conspiring with Carl. That really happened, but you can see how telling such a story without including the happiness that I often felt in the classroom could paint a false picture of life on a small campus. Petty grievances abound, to be sure, but that’s not the whole story.

While Lucky Hank takes a condescending view of faculty, it captures the human cost of corporatization in higher ed better than The Chair does. My interview source recommended it primarily because he feels that the ultimate villain — Dickie Pope, the short-lived president of Railton College — accurately reflects the disconnect between many university executives and the educational missions of the institutions that they ostensibly lead. But I quickly discovered that Lucky Hank nails many other truths about academe. There will be a few spoilers in this post, so you might want to save it for later if you prefer a pristine viewing experience. But I’m going to leave a lot out, so you might think of my review as little more than a back-cover blurb — the kind that helps you decide if you want to dig deeper and judge for yourself.

1. The Entitled Classroom

NIL deals have replaced team identity in college athletics with personal branding. Just so, jobs-based curricula have transformed the classroom into a cash register and the professor into a cashier. Here is this “A” that you paid for. Here is this degree. Have a nice day. In an age of gaslighting about disruption and innovation in higher ed, it is refreshing to see such an honest representation of the student-as-customer in Lucky Hank.

The show’s trailer teases an exchange between Hank Devereaux, Jr. (played by Bob Odenkirk) and Bartow Williams-Stevens (played by Jackson Kelly). Bartow’s parents try to grease his admission to Notre Dame with a sizable donation, but when that doesn’t work he ends up at Railton College in Hank’s creative writing workshop. The workshop itself reveals the perils of undergraduate peer review, which can sometimes amount to little more than sharing ignorance. But Hank is more or less content to allow students to congratulate each other on their writing until Bartow presses him for more honest feedback.

A professor would never say what Hank says in that scene, but there is some emotional truth to it. I can’t count the number of times I gave copious feedback on a student draft, only to see the same paper, virtually unchanged, submitted for the final assignment. I’d often make a joke of it, quoting my grandfather, who always said that you can’t steer a parked car. Get some pages behind you, I’d say, write forward without knowing where you’ll end up. Let your writing surprise you. Try to answer a question that remains unresolved. Then realize that those first thoughts are not your best thoughts. The most creative part of the writing process is revision — not brainstorming, not drafting.

It’s possible that students accept formal evaluation more readily in disciplines where competence seems less subjective. But the Maitland Jones story last fall shows that many young people believe a grade ought to reflect effort, not mastery, even in fields like chemistry. In writing classes, it’s really a curious phenomenon. Sure, everyone likes a pat on the back. But why would anyone pay for an educational experience that they think they’ve already mastered? I made no strides as a writer until my mentor taught me the importance of audience. The essay or poem, he said, is like a stranger knocking on the reader’s door. A mature writer doesn’t demand that the reader invite a crazy-haired story with a dirty face into their private life. Such a demand would be pointless anyway. A reader can always just slam the door in your story’s face. I still carry that question in the back of my thoughts while revising. Is this essay or story a good house guest for my ideal reader?

What Bartow really wants is to be told that he’s a genius, that his writing is fully formed. He gets a taste of this when Railton College pays George Saunders $50,000 to give a reading. Saunders visits Hank’s class as a favor and butters Bartow up, which only compounds the damage. The feud between Hank and Bartow simmers throughout the first season of Lucky Hank, and even though it is sometimes a little overblown it rings true to the life of an English professor.

2. The Pathology of Publishing

Lucky Hank leans hard into caricature. For instance, the English Department at Railton College checks most of the DEI boxes — disability, racial diversity, sexuality (including a biracial couple with an open marriage) — and most of these characters are flat. This can be delightful, such as when Billie Quigley, the most senior colleague in the department and a raging alcoholic, refers to Hank as “Spanky.” But profound insights into academe break through the slapstick, particularly in the character of Gracie DuBois (played by Suzanne Cryer).

Gracie is a second-wave feminist and poet possibly modeled after Sharon Olds. One day she shares a story with her class about why she gave her life to poetry. Her father, a military officer, paid no attention to her until she began memorizing poetry and reciting it before dinner. Thereafter, her father invited her to sit next to him at the dinner table in a chair that she later keeps in her office. After hearing this story, one of Gracie’s students says, “That’s really messed up.” It’s a revelation to Gracie, and she later tosses the chair in a dumpster.

But the daddy issues persist when Gracie learns that one of her poems will be published in The Atlantic. She shares the news at Hank’s annual dinner party for the department, and what would otherwise be cause for congratulation (and a little veiled jealousy among her colleagues) turns into a disturbing display of narcissism and/or trauma. Gracie is so overcome with her success that she retires to Hank’s porch and parades back and forth doing pelvic thrusts and chanting, “Gracie! Gracie! Gracie!” Then she braces herself against the railing and hisses, “I did it, Daddy.”

Oh, man. What a scene. But isn’t this the unsavory truth about academe’s broken reward system? The only thing that matters is the next publication, then the one after that. Maybe a MacArthur or a Guggenheim or — for the lucky few — a Pulitzer or National Book Award. No one succeeds at that rat race without at least some internalized version of Gracie! Gracie! Gracie!

I’ve had some luck with the lit mags. But I’ve wondered about the impulse that has, until recently, kept me at the grindstone of perpetual submissions for no compensation other than a stranger’s praise. Comedians are famous for having been damaged somehow, but maybe the same is true of writers. Maybe that kind of relentless drive for public approval can only spring from its absence somewhere during a writer’s formative years. Whatever the case, I’ve never been able to share Gracie’s elation for more than a moment or two without wondering what’s next? I know it’s not the publication-as-status-marker that matters. It’s whether the essay or story satisfies a reader’s hunger, assuages a problem in the world, or offers a gift of beauty to someone while they are hurting. I still care more than I’d like to admit about markers of prestige and the numbers game. But I know by now that madness lies that way. If an acceptance from The Atlantic makes you obsessively chant your own name, you’ve lost the original purpose of the written or spoken word.

3. The Prez as Control Freak

Season One of Lucky Hank turns on the prospect of faculty layoffs. The interim president of Railton College, one Dickie Pope, instructs each department chair to give him a list of names for this purpose. Perversely, this is not because the state legislature has cut funding to the institution or because Railton College is mired in a financial emergency. It’s because Dickie Pope believes the institution needs to be leaner. Therefore, he decides to not even ask legislators for the funding the college would otherwise expect to receive.

The premise of firing tenured faculty with no declaration of financial exigency is absurd. But a satire like Lucky Hank requires more attention to figurative truth than to plausibility, and it’s the perverseness of Dickie Pope’s executive action that rings true, even if it could never be carried out in real life. Jacob Rouse, Dean of Faculty at Railton, confesses at one point that Pope doesn’t even believe in public education. Indeed, Pope’s motivation for forcing the layoffs — one spoiler I’ll avoid for now — becomes clear in the final episode, and it has nothing whatever to do with higher learning.

I don’t expect that most college presidents require their executive secretaries to sharpen all of their pencils to the same length, as Dickie Pope does, or to correct them all if one pencil grows a little shorter than the other, or to discard them when they reach exactly 18 centimeters. But it’s a fine metaphor for micromanagement. As Hank Devereaux says, in a moment of solidarity with Pope’s secretary, “Some days are just about pencils.” I can imagine a great writing prompt using Pope’s character to illustrate the power of nuance over exposition. How do you suggest a character’s obsessive need for control without spelling it out for the reader? How about by showing them leave a room in a huff, mussing up the Venetian blinds on their way out? Using the pencils and the Venetian blinds as a start, brainstorm three other scenes where a character like Dickie Pope would project his need for absolute control onto physical objects…

Most college presidents burnish their personal brands through fundraising, and Pope is no exception. He persuades a local billionaire, who just happens to share a name with the disgraced financier Jeffrey Epstein, to donate $40 million for the construction of a new technical center. In a weak effort to avoid disgraceful connotations, Pope suggests adding a middle initial to the building’s title, as in “The Jeffrey Q. Epstein Technical Careers Center.” It turns out that the “Q” is worth $10 million, because Epstein hates it so much that he renegotiates his donation. I’m not sure I’ve ever encountered such a succinct and precise parody of corporate branding in higher ed.

Now, you might be forgiven for styling me a hypocrite on this front because of all the interviews I’ve been doing about employability and my own aspirations to find a non-academic job. But as Jennifer B. wrote in a discussion thread the other day, you don’t translate a CV into a resume. You write a CV, and you write a resume. The two have almost nothing in common. That’s how I feel about teaching and industry training. Do soft skills from liberal arts teaching have value in industry? Without a doubt. But the why and the how of teaching and training could not be more distinct. The Jeffrey Q. Epstein Technical Careers Center is obscene because it belongs at a corporate headquarters or vocational school, not at a liberal arts campus. Teaching American literature has its own integrity. It does not exist for the purpose of corporate training.

The writers of Lucky Hank seem to agree with me, because who do you think is invited to write and perform an original poem for the Epstein Center’s groundbreaking ceremony? And who do you think accepts the invitation because it makes her feel important? And what does this say about the integrity of art that cozies up to institutional power, or the ability of art to flourish in an environment where even poetry must align with the brand?

Hank Devereaux, Jr. is no hero, and Lucky Hank illuminates many unsavory truths about the state of academe. If you watch the series, you might just as easily be crying as laughing by the end of it. But it reveals something about the lives of faculty that few film productions have managed to capture. Professors aren’t saints. They aren’t martyrs. They carry the same buried wounds, petty grudges, and validation needs that everyone else does, and if they sometimes seem intransigent or mired in a turf-bound mentality, it might be because they feel powerless. Might this not be one of the reasons behind Gracie’s craving for the next big publication? The illusion that she can shake that fresh copy of The Atlantic in the face of an institution that long ago stopped caring about what she actually does?

Well-done, good sir.