A lost son comes home

Searching for ancestors and finding chosen family in Moravia

Earlier this spring, when I knew I’d be participating in Prague Summer, I began researching my family roots in Moravia, expecting that I’d make a pilgrimage to those ancestral places. I wanted to share more of our family story with my children than my elders had been able to share with me. Assembling a family tree has also become a ritual explicitly tied to my transition away from academe, a conscious attempt to replace old anchors of identity with more durable cornerstones.

With the help of Mary Sramek Levesque and Richard D’Amelio, I was able to uncover the story of Maria Obrdlíková, one of my ancestral mothers, and Karel Josef Doležal, the first of my Czech ancestors to immigrate. The only thing left was to go to those places myself, hear the language, smell the earth, touch the walls of the houses where the people who made me had been born.

I first visited Prague in 2007. I didn’t know anything about family origins then. I’d heard rumors that our family was based somewhere near Pilsen and that they had been potato farmers (which supposedly accounted for my large, thick hands). I wandered around Prague, took a train to Pilsen, and backpacked around Vimperk, a scenic area near the German border that is more than a hundred miles west of my family’s real place of origin in Moravia. A great deal of that trip was pure fiction. I’d done no due diligence to educate myself, and so I was free to see what I wished to see.

But the trip this summer would be different. I knew of at least four ancestral villages where I expected to find burial sites, and with the help of this 1835 map and the Moravian State Archives in Brno, I could say with certainty that my ancestor František Doležal had been born in House #1 in Sokolí in 1814. And that his eldest son, Karel, had been born in House #17 in 1859. Sokolí is a tiny place, and the house numbers have not changed in all these years. I found a tour guide in Brno who contacted the current owner of House #1. He was eager to meet me and could introduce me to the owner of House #17.

What was I really looking for? There are a dozen different ways to define family. A popular option now is claiming a chosen family: not blood relatives necessarily, but people that provide support and belonging. As Jan Peppler writes, “I’m done comparing my friends to family. My friends are my family. My family is large.” Patricia Hampl felt that way when she came to Prague in 1975 to seek her family roots. Hampl decided on a whim to step out of a queue at a travel agency, where she’d been planning to get directions to an ancestral village in Bohemia. Instead, she searched for belonging in the history and artistic heritage of the Czech Republic. As I wrote two weeks ago, I quarreled with Hampl as I read her memoir, because I felt that tracking a bloodline was still important, and that doing so did not need to exclude the national story. Hampl explored her Bohemian roots later (these things matter more when you’re older), and her lovely memoir The Florist’s Daughter traces ancestry within the larger historical currents of her youth.

I care about bloodlines because so much of American history has been defined by erasure. Immigrants are encouraged to abandon their cultural anchors, learn English, serve in the military, take out a mortgage, and pledge allegiance to the flag. Kao Kalia Yang and many other writers with histories of forced emigration write against this violence to family heritage. The explicit purpose of the Native American Holocaust was erasure, including the cultural genocide in mandatory boarding schools, where the philosophy was “Kill the Indian, and save the man.” The books and movies and television programs, from Toni Morrison’s Song of Solomon to Stephen Satterfield’s High on the Hog, that seek to reclaim what slavery and racism have tried to erase, are too numerous to name.

My ancestors were never torn from their mother’s arms, forced to abandon their language, or gunned down by the U.S. Cavalry in their very homes. They were shamed for being “Bo-hunks,” an epithet that my grandfather said would always make him fighting mad. Even writers like Willa Cather, a friend to Czechs, trucked in denigrating stereotypes about Bohemians as drunk, irrational, and sexually promiscuous, as my former student, K.E. Daft, reveals in this incredible essay.

But mostly my family decided to assimilate. Either the first generation deliberately withheld its heritage from the second generation, or the second generation dropped the ball. My father, uncle, and aunt grew up eating their Czech grandmother’s cooking, but learned next to nothing about her family. This silence defined Hampl’s relationship with her grandmother, as well. There were other priorities: surviving the Great Depression, for instance, and feeding large families. My ancestor Karel may have wanted to forget much of his life in Moravia. He was eight years old when his mother died, eleven when he lost his father, and twelve when his sister Maria died. The American Dream came true for Karel in Nebraska, and that was the story he wanted to pass on. I can’t blame him.

But I wanted the whole truth, as much of it as I could uncover. I wanted something real, a pillar rising from the fog of history that I could grasp and say, “Here I am. Here is where my family’s story begins.”

I met my guide, Helena, early one morning and set off for Zakřany (Zahk-shawn-ee), a village where many forebears of Karel Doležal’s wife, Mary Matulková, had been born and, presumably, buried. It was a beautiful day, sunny but cool, and I saw wild poppies blooming red in the fields. We met a helpful woman in the cemetery and showed her our printouts of family names: Matulka, Hradecky, Prochazka, Posádková. There were headstones with some of those names, but none of them matched my family tree. The woman wrung her hands. “What a shame,” she told Helena, “That he has come all this way and cannot find anyone.”

I admired the memorials. They were like little shrines with photographs of the departed, fresh flowers, and gravel, like you see in French gardens. Many headstones were etched in gold, much fancier than anything I’d seen in country graveyards back home. But the dates were strangely recent.

Helena told me, as we drove toward the city center, that Czech grave plots are leased. If a family fails to pay the lease for a period of years, usually a decade, then the headstones and coffin are removed and the plot is leased to another family. The bones stay where they are and new burials happen on top of the old. I’d heard of a similar practice in New Orleans. But I was a little shocked to think that my ancestors were likely buried inches from where I’d just been walking. Even if I could verify the place of their interment in the archives, there was no way to know which plot, exactly, held them. And thus no way to truly pay my respects.

We had no better luck in the registry at the municipal office. The file cabinets went back only to the early 1900s, and the big registries, handwritten in German, were no different from the digitized records I’d already been probing with genealogists. Everyone said the records must be there, that Czech records were excellent. But they were nowhere to be found. So we pressed on.

The road into Sokolí runs beneath a canopy of mature beeches, oaks, and pines. Lunch was waiting for us at House #1. Jan, as I’ll call the man living there, was a bachelor, and he had invited his sister and brother-in-law from Třebíč to meet me.

I knew the house from aerial photos online, but I was not prepared for how large it was. The north wall stretched at least two hundred feet. It was a pretty house, painted cream, with a thick bush of tea roses near one corner.

Jan met us at the gate and invited us in through the backyard, where half a dozen chickens roamed. There were grapes growing over the interior walls, several walnut trees laden with fruit, pigeon houses up along the roof, and raspberry canes. I could now see that much of the north wall was something more like a barn, with several stalls originally meant for cows that were now repurposed for storage.

The door opened into the kitchen, where Jan’s sister, Anna, was preparing a feast. The smell of potatoes, pork, and gingerbread wrapped me like a blanket. Jan invited us into the living room, where he had set up a dining table, and poured us all a glass of becherovka, a liqueur made of 20 herbs and spices. We raised our glasses and said “Na zdraví!” and drank.

The meal was the best I’ve had during my visit. Beef bouillon with liver dumplings to start, then pork schnitzel, a creamy potato salad with grated carrots, boiled potatoes with butter, and a refreshing cucumber salad. Anna kept urging me to have more, please to have more, and I did my best. Then we shared gingerbread cake drizzled with chocolate, Jan’s own honey, and a glass of slivovice, a homemade plum brandy that burned going down, like moonshine.

We chatted, a little awkwardly, with Helena translating. Everyone but Helena was old enough to be my grandparent, and we were all strangers, bound only by this house. But as I took another sip of slivovice and felt it light me up straight to my core, Jan shared a glimpse into why he might have been interested in meeting me.

In the early 1990s, he said, after the Velvet Revolution, two men from Nebraska had returned to this very house. Jan was sitting with them at the kitchen table when one of them began to cry. The man pointed to three marks in the wood that he had carved with a penknife as a boy. Jan led me back into the kitchen and peeled back the oilcloth, and sure enough, there they were, those three little gashes from a mischievous boy. Jan’s grandfather had purchased the house from the Doležals in the 1880s, around the time that everyone seemed to be leaving for Nebraska, and it had been in his family ever since.

I wondered about the story. It was unlikely that anyone who was a child in the 1880s would still be alive or healthy enough for international travel in the 1990s. Did I misunderstand the year that Jan’s family had purchased the home? Could Jan have misunderstood who had made the marks on the table (maybe a father told this story to his son, who was one of the Nebraska men who returned to see for himself)?

But it was a pretty tale, and the table was old, and I embraced it as one of those anchors I had been looking for: a place where my family had lived, where meals were shared along with births and deaths, a place that had now remained in Jan’s family for three generations. It would have been a place where my Karel might have gone to play with the cousins that he followed to Nebraska. A place that would have seen its share of stern language and whippings, but also a place where my family knew love. A place where Jan and Anna were showing me, with their stories and becherovka and slivovice and soul-replenishing food, that I was welcome as their chosen family.

They could have met me at the gate or not answered the knock at all. But they let me in.

After two hours, maybe three, it was time to go. There was some confusion about which House #17 we meant, so I pulled out the map on my phone and pointed to the place. Jan raised his finger and nodded. He knew just where it was.

House #17 sits across the Jihlava River on a sizable acreage that is now an equestrian farm. Like House #1, it is built in an L shape, easily identifiable on the 1835 map and satellite imagery now. The plaster walls are painted white, a pretty contrast with the red tile roof.

This was the place where Maria Obdrlíková came to live when she first married František Nováček, the place where she gave birth to four children, where her son Johann died when he was two years old. Then Maria lost her husband and married his cousin, František Doležal, with whom she had three more children. Karel was born in House #17, and both of his parents and his sister Maria died there.

I knew from old maps that the Nováčeks and Doležals owned something like a third of the farmland around Sokolí, so I did not imagine that anyone ever starved in that house. Every hand would have been needed, but it felt like a place of abundance. The backyard was lined with apple trees, gooseberry bushes, and flowers. Standing beneath one of the apple trees and looking back across the river, where timber rose along the hilltop, I could almost imagine that I was back in my parents’ orchard in Montana.

House #17 knew some happy days. František Nováček, the eldest of Maria’s sons, inherited the place after all of his elders died. Around that time he married a woman named Rosalie. Census records show that they were successful. František II began with three cows, somewhere around 1880, and by 1890 he had more than doubled his livestock with eight cows. Not bad, František. By the 1910 census, his son (František III), had taken over as head of household, and his mother, Rosalie, was still living there.

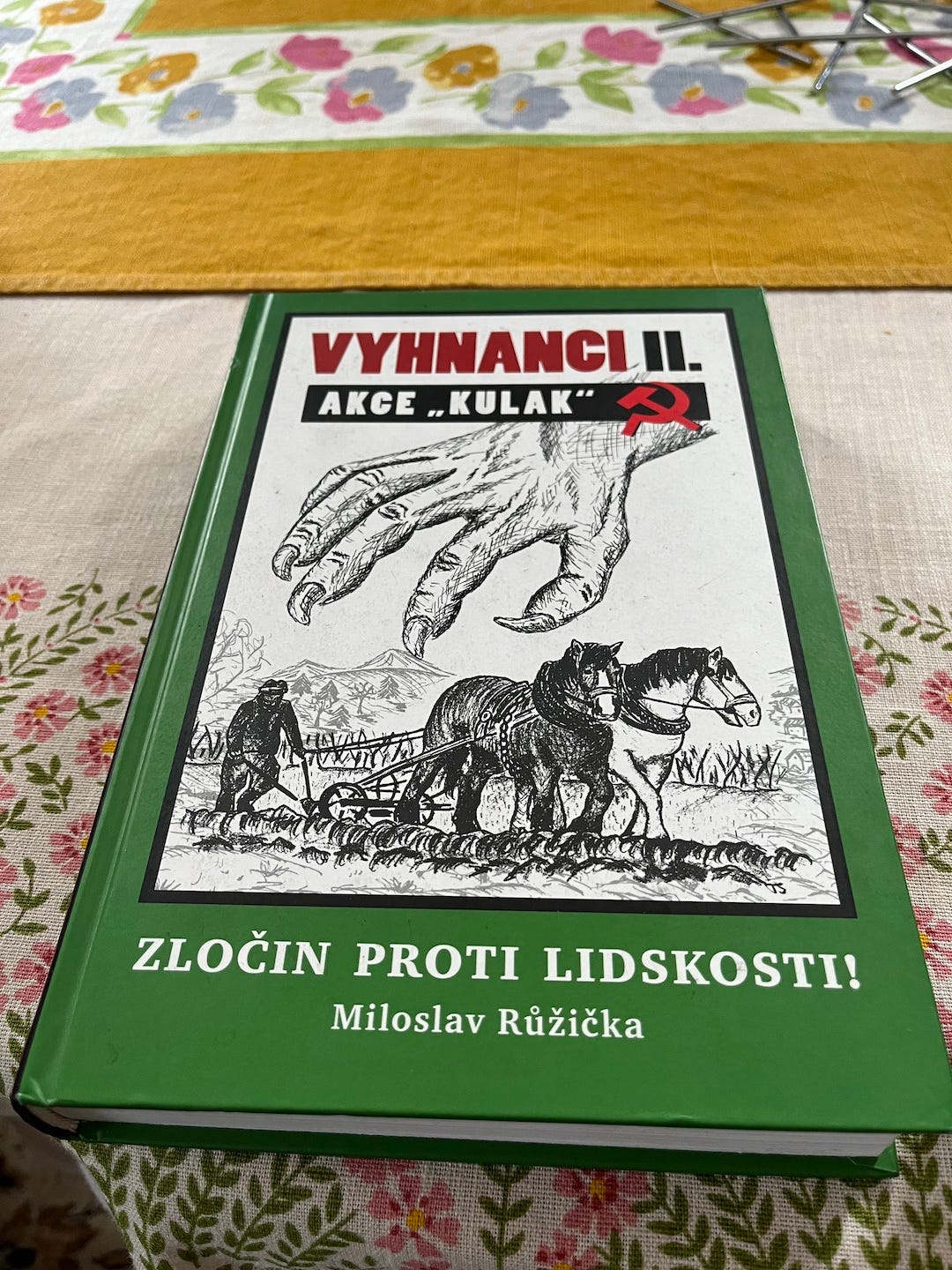

But the farm fell on hard times under Communist rule. The Nováčeks refused to join the communist co-op farms. As a result, the Soviets required them to record artificially high crop yields, and when the Nováčeks fell short, levied steep fines. Eventually this caused the family to abandon the farm, essentially ceding it to the state for decades, before the land was restituted to their descendants after the Velvet Revolution. Fortunately, the house was still standing, and the current owner, a lifelong horseman, purchased it from a Nováček that I have not been able to identify.

House #17 is now once again a happy place. The Jihlava murmurs along the fields. The wind sighs among the beeches and apple trees. It is a pleasure to know that the house and its acres have fallen into good hands.

On our way back across the river, we discovered that the Sokolí cemetery sits maybe fifty yards from one of the horse fields. This was the final piece, I thought. The other villages were no more than rolls of the dice, but I knew for a fact that Karel’s parents had died in Sokolí. For more than a week I had seen the memorials that other families had made for their loved ones. I am a typically stoic man, but if anything could bring me to tears it would be standing before those names, František Doležal and Maria Doležalová, running my fingers over the dates, knowing that I came from them. That I could tell my three children the same.

More than a house, which can pass through many hands, a grave is an objective fact. A final resting place. A pebble of truth in a world crazy with lies.

I should have known better. Of course there were no names. Nearly everyone who could have paid the lease on the plots had moved to Nebraska in 1877 or soon after. House #1 left the family shortly after that. Even if Karel had tried to send money home for a time to keep the headstones intact, he was 18 when he left and 81 when he died. He might well have wanted to let those old chapters fade. The Nováčeks were still around for a time, but they had moved on before restitution in the early 1990s, when they sold the place to the current owner. More than twenty years have passed between now and then. Of course the plots had been leased to others.

It was a tiny graveyard, rimmed by a neat stone fence and lined with arbor vitae, lindens, and birch. A beautiful place. I stood there quietly, certain that one of my fathers and one of my mothers lay somewhere nearby. But without the names on a stone, it was hard not to feel that they, too, had been erased.

We all fade in the end. Before I was married or had children, I was certain that I wanted my ashes spread over the crags in the Selway-Bitterroot Wilderness in Idaho and at least a few emptied into the Selway River, my son’s namesake. But now I understand the value of family graves. They, too, are homes. And this was one home that immigration had taken away.

I wasn’t angry at anyone. It was better that other families had a chance to honor their loved ones in a place that everyone else in my family had abandoned long ago. But I could not help thinking of František and Maria lying there forgotten (not them, I know, I know, but still). It made me sad. I thought of all the reasons that Karel had for leaving Sokolí, how glad I would have been to flee the village if I had been him, and I wondered if maybe feeling that way was the point. Sadness cannot be etched into granite. You can’t run your finger over emotion the way you can touch engraved names and dates. But feeling sorrow in that place might have been the closest I could get to the truth of what it was to live there, the truth of what Sokolí came to mean for my people, the Doležals and the Obrdlíks and the Nováčeks.

I carried that feeling with me back to Brno, back to Prague. I will always carry it alongside the warmth I felt in House #1, where strangers embraced me like a long-lost son.

This is so rich. The "I know, I know, but still" says it all, in a way.

But I also wonder why that hospitality that we extend to others/strangers depends on the fact that they are "family." That feeling of wanting to claim your kin in that tiny graveyard is a lovely moment in its yearning, but also in its humanity. Our official connections blurred or erased, we can still choose kinship.

Like you, we have no graves of direct ancestors left, but just walking in the same yard of the house where my ancestors lived was more meaningful to me. Beautifully written.