One of my coworkers on a fire crew in Montana used to bury the tiny Tabasco bottles that come in MREs (Meals Ready to Eat). Mike claimed that he was seeding the ground for a future anthropologist who would unearth one of those pinkie-sized bottles and go on to write a thesis, “The Tabasco-Eating Gnomes of North America.”

Stranger things have been published. I would not be surprised if someone without a better idea were one day inspired to explain why there are many more social media postings about syllabus preparation in August, compared to January, even though both months mark the beginning of a new semester.

Not counting my two sabbatical years, this is the first August since 2001 that I won’t be drafting course objectives and policies that none of my students will read. It seems fitting that the Latin word “syllabus” (for “list”) derives from a misreading of the Greek “sittybas” (for “label”). According to Merriam-Webster, the first known use of “syllabus” to describe an outline or summary of a longer document dates to 1656, when Thomas Blount canonized the word in his Glossographia.

Mike has retired from firefighting, but he would be pleased to know that hundreds of thousands of academics are presently bedeviled by a task whose very name derives from a transcriber’s mistake.

August feels more monumental because it is the beginning of the academic year, not merely the fall semester, and because everyone is groaning back to work after two or three months of unstructured freedom, compared to the three short weeks of the winter holiday. I thought, until recently, that summer break was an arcane holdover from the agricultural calendar, when the majority of American children were needed back on the farm. But, as historian Kenneth Gold explains, farm kids typically attended school in summer and winter and took longer breaks during spring planting and fall harvest. Summer break was conceived by education reformers in the late nineteenth century, who advocated for standardizing the school calendar to minimize differences between rural and urban students.

Every few years someone publishes an op-ed arguing that summer vacation is bad for kids. It disproportionately harms low-income students, who suffer academic losses during the long break. Summer break also penalizes single parents and families with less flexible work schedules. But the angst I see on Facebook and Twitter from faculty – and that I once felt myself – suggests that maybe the long summer holiday isn’t good for anyone.

There is a sinister message in the phrase Back to School that applies as equally to professors as to grade-school students. It signifies a uniquely American attitude: the notion that once we make it to summer, we are released from the burden of learning and must be dragged back reluctantly every year. It would not be a stretch to link this escapist mentality to what some call Americanitis, a propensity for overwork that eventually negates itself with malaise and burnout.

It’s not the notion of holiday that is the problem so much as the sense that as Americans we must earn the holiday by exhausting ourselves. Make it to Fall Break, make it to Thanksgiving, make it to Christmas or Hanukkah. Rinse and repeat. Remote work remains popular because people are tired of commutes and long days at the office, where phenomena like “time macho” (I’m going to stay the longest at my desk and shame you for leaving earlier) prevail. But now people take their work everywhere: to the Airbnb, to the lake cabin, to the beach. We either fall into vacations like frat boys soused to the point of death, so far gone that it might take us a week or more to really recover, or we simply forget what it means to leave the laptop behind.

I began this post with the thought that I might write a post-academic syllabus for myself, laying out some objectives for the fall, maybe for the year. But I find myself resisting the notion, because my tendency is always to add one more thing, the way I’d sometimes assign two Hawthorne stories for a fifty-minute period and realize later that I could only meaningfully cover one.

The best syllabi I ever wrote were those that had some long arcs with flexibility built into the middle. Nature Writing began with a quiz, “Where You At?,” which helped students probe their ignorance of the ecological places they called home, and ended with a personal essay or short story that allowed them to actively define a sense of place through narrative. The quiz established the problem of ecological illiteracy, the middle section of the course tried to chip away at it, and the creative writing assignment at the end was meant to transfer ownership of the problem from me, the professor, to the student. Anyone who has read Bill McKibben’s Eaarth or Robin Wall Kimmerer’s Braiding Sweetgrass knows that trying to understand “where we at” is a lifelong endeavor.

Those who advocate for year-round school are arguing for something like that: the notion that we should always be learning something or teaching something, that we should not fall off an educational cliff in May or June and then try to climb back up it in August. But successfully avoiding the boom and bust model for education would also mean redefining how much we ask of ourselves day to day, so that the prospect of school in every season did not seem like a crush of work with no escape. For many academics, Fall Break is just a chance to catch up on grading, and the longer winter holiday comes with committee work attached. Summer is the only time to enjoy a real break: a chance to lie in a hammock or breathe the musk of tomato vines or kill half the day on a long bike ride.

To my shame, I embraced those all-or-nothing terms for most of my academic life. I never saw the sandhill crane migration in Nebraska, because I thought of Nebraska as the place I went to finish my graduate degree. My real life began in mid-May, when I hit the road West and disappeared into the wilderness for three months with my trail crew, and it ended in August, when I had to start thinking about syllabi.

One of the most significant breakthroughs in my life came just a few years after I’d taken a faculty position in Iowa. I learned that I’d been selected for jury duty, and in my rural county that meant a full month’s service. July was the only month that would work, and I was forced to give up my summer rambles for that year. I was not happy about that, but I was determined not to spend the summer feeling sorry for myself, so I bought a road bike and planted my first garden. It might have been coincidence that my future wife moved to Des Moines that very summer, and that I was able to scoop her up before anyone else could. But I suspect that there was also something about my mindset — the choice to mindfully inhabit my home place after fate had taken my escape route away — that made me more open to relationship, and ultimately to starting a family.

My outlook in graduate school and for many years as a faculty member was a symptom of Americanitis. Work, work, work, and then run away. Live in place for a while, and then move on. Make it to the holiday, make it to sabbatical, make it to retirement.

I suppose if I have an objective for the year, it might be to work a little and rest a little every day, and to take an occasional holiday. By this I mean something very different from what kids these days call “grinding,” even though I can do that with the best of them. I plan to keep pitching my novel to agents, mulling a design for my memoir-in-progress, and continuing the conversation with you, dear reader, every Tuesday. But I also want to be available to my wife and children, to find a stride for work life that does not leave me searching for the booziest beer at dinnertime. In the words of Gary Snyder, I’d like to learn how to reinhabit my own life.

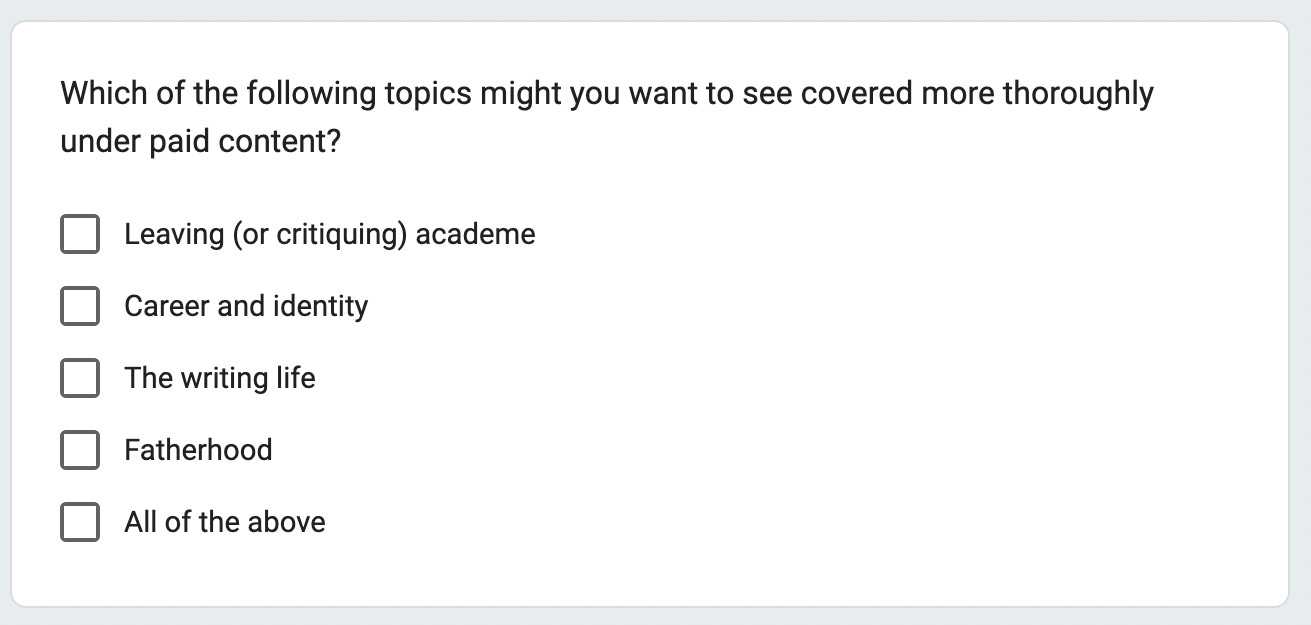

Thanks to your support, I am now approaching the point at which it might make sense to add paid content to The Recovering Academic. Over the next few months, as I plan the future of this series, I’d be grateful for your feedback on topics that you’d like to see covered more deeply or new features that you’d like to see added. If you’d like to make suggestions, please complete this Google Form. Or you can always send me a note at dolezaljosh@gmail.com.

Not your topic, but now I find myself very curious to know why American students aren't reading the syllabus.