Can a novelist be an intuitive neuroscientist?

A thought experiment about Willa Cather and neurotheology

Last week I joined many friends at the International Cather Seminar in New York City. You might wonder why a recovering academic would want to attend an academic conference. Isn’t that a little like falling off the wagon?

It’s certainly true that listening to three panelists read their research aloud with no visual aids is sometimes stultifying. But it’s the fellowship afterward — in the lobby, over meals — that really binds a scholarly community together. Cather Studies is small enough to feel like a family, and I’ve been part of these gatherings since 1997, my first year in graduate school. So it was fortifying to renew those ties. And it was fun to give a presentation of my own, which I’ll share with you today.

As you know from our earlier conversations on epiphany in The Song of the Lark and Lucy Gayheart, Willa Cather understood how the body drives the creative mind better than the scientists of her time did. In fact, I think neuroscientists should mine Cather’s novels for research ideas. She is so good at capturing her characters’ inner lives that her books contain dozens of testable hypotheses about creativity, imagination, and memory. I’ll even be so bold as to say that Cather’s novel Death Comes for the Archbishop (first published in 1927) offers a representation of how the body influences spirituality that is still cutting-edge today.

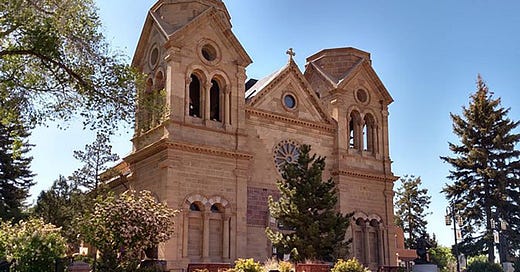

Death Comes for the Archbishop follows two French priests — Father Latour and Father Vaillant — on a mission to New Mexico shortly after its annexation by the U.S. in 1848. There are some dramatic moments, such as the priests’ narrow escape from a murderous frontiersman, but images drive the story more than plot. Latour becomes an archbishop and achieves his goal of building a cathedral in Santa Fe before he dies. In fact, Cather modeled his project on the Cathedral Basilica pictured above. But you don’t need to be a history buff to love Death Comes for the Archbishop. The richness of the novel comes from Latour’s daily meditations, from the slow burn of his inner life.

I’m not sure how other people get research ideas, but for me the process almost always begins with a feeling of strangeness. I’ll be reading along and think Huh, that’s weird. Something about a word or a passage flashes from the page and demands explanation. What is a clinical term like “retina” doing in a desert scene? Why do so many religious moments in Death Comes for the Archbishop seem empty of anything supernatural? And why would Cather describe a priest as sitting “in the middle of his consciousness” during his dying days — shouldn’t a man of the cloth be meditating on heaven in those final hours? To try to answer some of these questions, I turn to the emerging branch of neuroscience known as neurotheology.

Neurotheology, or “spiritual neuroscience,” is a multidisciplinary field most commonly grounded in biology. Some biologists, such as Dean Hamer, maintain that humans have a “God gene” that predisposes them to religious beliefs. But neuroscientists are typically more cautious about claiming that spiritual experiences originate purely in the body. Instead, neuroscience shows that religious concepts and rituals can have a profound impact on the brain regardless of whether any supernatural influence is involved.

Neurotheology helps explain Bishop Latour’s faith in Death Comes for the Archbishop because the priest is so attuned to his body. But really I ought to flip that around. Cather helps us understand neurotheology because she expertly captured the physical triggers for spiritual experiences half a century before fMRI scans came along.

What is neurotheology?

In his new book The Varieties of Spiritual Experience, Andrew Newberg and his coauthor David Yaden measure how meditation, prayer, and other religious practices shape the brain. Religious people might practice religious rituals in hopes of comfort or transport, but even atheists or agnostics who scorn religious practices may experience feelings of wonder or universal love that they define as spiritual. And so Newberg and Yaden try to minimize confusion between “religion” and “spirituality.” For instance, they explain that the word religion has communal origins, deriving from religio (for “ritual”) or religãre (“to bind”). Spiritus is Latin for “breath,” suggesting more private forms of illumination. It’s an imperfect distinction, but thinking of religion as a collective activity and spirituality as a private experience is useful for examining Death Comes for the Archbishop.

Neurotheology does not deny spontaneous forms of epiphany, but it shows that in many other cases the “proximal triggers” for spiritual transport are known. These include but are not limited to personality types, genetics, mindset, religious rituals and rites of passage, near-death experiences and trauma, psychopharmacology (psychedelics), and neurostimulation.1 Cather unfortunately does not show Father Latour and Father Vaillant experimenting with peyote in New Mexico. But she does describe several other known triggers for spiritual experience that fit Newberg’s and Yaden’s categories. I’ll focus on just two of these: near-death experiences and religious rituals.

Near-death experiences and epiphany

People often describe close encounters with death as out-of-body experiences — moving toward a bright light or literally watching themselves on the operating table from above. But a brush with death is also a physical experience. The actor Sharon Stone felt bathed in a “vortex of white light” during a hemorrhagic stroke, but the sensation had a clear physical stimulus. Neurotheology pulls no punches in demonstrating that the body, strained to its breaking point, is capable of producing or contributing to spiritual experiences.

Father Latour finds himself in just such a predicament when we first meet him in Book One of Cather’s novel. He has lost his way in the desert, “somewhere in central New Mexico,” and his desperation manifests as a kind of blindness. He can’t distinguish anything in the “monotonous” landscape. The “conical red hills” seem to repeat themselves infinitely like a “geometrical nightmare.”

We know from this first glimpse of Latour that his religious sensibility is aesthetic. He is “sensitive to the shape of things.” And so his physical and spiritual suffering are magnified by “the blunted pyramid, repeated so many times upon his retina and crowding down upon him in the heat.” What is “retina” doing there, if Cather isn’t signalizing a scientific interest in her character?

Latour is also suffering from thirst: “Since morning he had had a feeling of illness; the taste of fever in his mouth, and alarming seizures of vertigo.” These are clear symptoms of heat stroke that, left untreated under the desert sun, would mean certain death. But just as a hemorrhagic stroke altered Sharon Stone’s consciousness, so Latour’s visual disorientation and dizziness precondition him for a spiritual experience.

The first of these is his discovery of a cruciform tree: a juniper with “two lateral, flat-lying branches, with a little crest of green in the centre, just above the cleavage.” Latour kneels before the tree, praying for half an hour before continuing on. He tries to “[blot] himself out of his own consciousness” by meditating on his agonizing thirst as akin to Christ’s suffering on the cross.

It may be impossible to say whether desiring a spiritual experience has the power to produce more epiphanies, but Newberg and Yaden show that those who identify as “religious” or “spiritual” do predictably report more spiritual encounters than atheists or agnostics do. While it may seem like common sense that we all see what we expect to see in the world around us, it is worth noting that Latour’s physical strain, accompanied by his conscious devotions, all but guarantee that he will interpret his survival as a sign of divine mercy. Thus, when his mare leads him to a hidden stream known by its Mexican inhabitants as Agua Secreta, Latour cannot see it as anything but miraculous.

Religious rituals and epiphany

Just as desiring a spiritual breakthrough may predispose someone to interpret their experience in that way, so do religious rituals observed with others in a setting expressly built for that purpose, such as a sanctuary, seem to increase the likelihood of spiritual experiences. Whether a ceremony involves just two people or a crowd, there is power in consciously sharing a ritual with others. I’ve often felt this uplift while running in a crowd. Not only can I run much faster on race day than I can while training alone, there’s a joy in the group effort that buoys me. Newberg and Yaden describe this phenomenon in religious contexts as “synchrony.” As someone raised in the Pentecostal Church, I can attest that it’s far more likely to see people speaking in tongues or being “slain in the spirit” in a crowded tent meeting than it is if they are walking alone in a meadow.

Perhaps the clearest example of spiritual synchrony is Father Latour’s encounter with Sada, a Mexican woman enslaved by an American family. Latour has fallen into a malaise as the Christmas season approaches. His devotions feel hollow, and he sees his mission as a failure. He is in desperate need of spiritual renewal. Lying in bed one night, Latour reflects that “[h]is great diocese was still a heathen country. The Indians traveled their old road of fear and darkness, battling with evil omens and ancient shadows. The Mexicans were children who played with their religion.” Unable to sleep, Latour dresses and walks to the church to pray. He discovers Sada crouching in the doorway of the sacristy and realizes that she has risked the wrath of her oppressors by slipping out to the church to pray.

Latour invites Sada into the sanctuary, and they pray together by candlelight before the Holy Mother. The scene has all the hallmarks of synchrony: two people gathering in hopes of a spiritual experience in a place expressly devoted to that purpose.

Indeed, Sada’s spiritual ecstasy lifts Latour from his despair:

“He was able to feel, kneeling beside her, the preciousness of the things of the altar to her who was without possessions; the tapers, the image of the Virgin, the figures of the saints, the Cross that took away indignity from suffering and made pain and poverty a means of fellowship with Christ… Only a Woman, divine, could know all that a woman can suffer.”

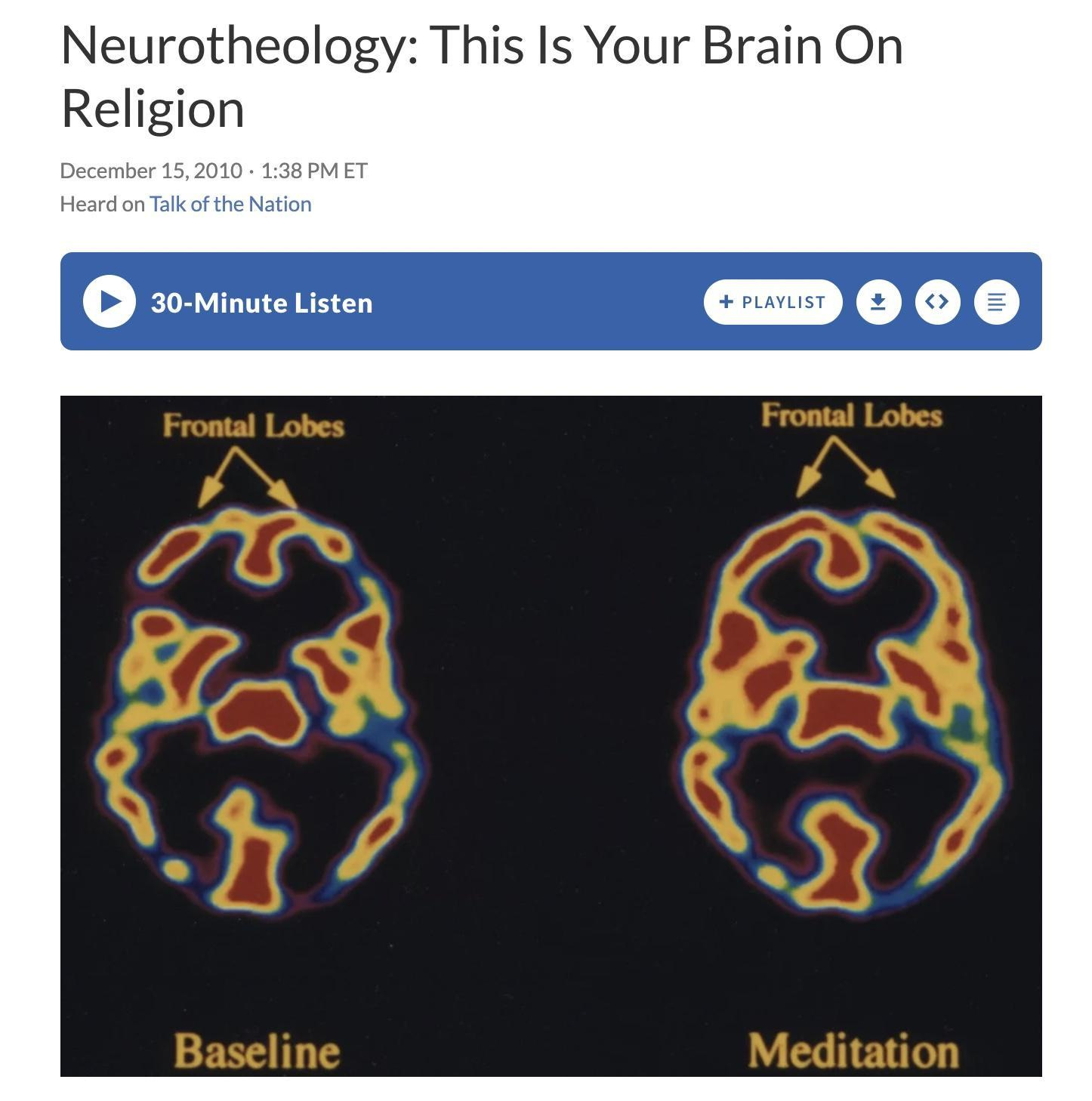

The kind of spiritual transformation that Cather describes in Latour would be visible in his brain if he were a real person; Newberg and Yaden measure spiritual experiences like this with fMRI. It doesn’t matter, for the purposes of neurotheology, whether Latour’s epiphany is conjured purely from the ritual or sparked by the Holy Spirit. If he were a real person rather than a character, the change in his brain activity would be the same either way.

As an atheist myself, I have often been struck by how cerebral Latour’s spiritual experiences are. That is, even when he seems to feel genuine emotion, the feeling stems from an idea, often a nuanced and subtle one. There are no sudden transformations for Father Latour; his inner life is a slow burn. I’ve often wondered: does Bishop Latour really believe in God, or does he simply find more beauty in the ceremonies and artifacts of the church than in anything else? Is his practice of Catholicism truly distinguishable from Cather’s practice of art?

Latour’s spiritual experience with Sada could be seen as purely aesthetic, merely substituting faith for poetry or visual art.2 It’s the conceptual meaning of Sada’s devotion that moves the Bishop. This is one of many scenes in the novel that are drawn as much from a character’s interior as from their surroundings:

“The beautiful concept of Mary pierced the priest's heart like a sword. ‘O Sacred Heart of Mary!’ Sada murmured by his side, and he felt how that name was food and raiment, friend and mother to her. He received the miracle in her heart into his own, saw through her eyes, knew that his poverty was as bleak as hers. When the Kingdom of Heaven had first come into the world, into a cruel world of torture and slaves and masters, He who brought it had said, ‘And whosoever is least among you, the same shall be first in the Kingdom of Heaven.’ This church was Sada's house, and he was a servant in it.”

One might say that Latour’s inspiration is an imaginative construct. Cather simulates, in his character, the very habit that she described in herself as a young woman, when she would visit her immigrant neighbors and feel like she had “actually got inside another person’s skin.” Indeed, it is the very elusiveness of Cather’s spirituality — the fact that Death Comes for the Archbishop can support both literal and figurative interpretations of epiphany — that invites a comparison to neurotheology.

I can see no quarrel between Newberg’s and Yaden’s research and Cather’s definition of miracles in one of Latour’s unforgettable lines:

“Where there is great love there are always miracles. One might almost say that an apparition is human vision corrected by divine love. ... The Miracles of the Church seem to me to rest not so much upon faces or voices or healing power coming suddenly near to us from afar off, but upon our perceptions being made finer, so that for a moment our eyes can see and our ears can hear what is there about us always.”

One of the wonders of neuroscience is that it can map the exact location of our spiritual moments, and if any one of us were to experience the kind of illumination that Latour describes while undergoing an fMRI scan, it would not matter whether we were Christians or biologists or poets: that heightened awareness would light up the same part of our brains.

The mere fact that spiritual sensations — such as a sense of divine presence — may be induced by electrical stimulation of the brain or a good magic mushroom makes me wonder why Newberg and Yaden are so careful to avoid ruling out supernatural influences, except as a strategy for protecting their funding in a politically volatile time. But perhaps their humility on this count is, in fact, a measure of their scientific integrity.

Indeed, this scene never sat well with my students. Latour prays with Sada and then lets her slip back into the night, back into enslavement. Why doesn’t he help her run away from her oppressors for good? He is a bad priest by today’s activist standards. I’ll admit that there is something unsavory about Latour drawing spiritual fulfillment from a woman that he seems to perceive in purely symbolic terms. But there are other examples in the novel where he advocates for the defenseless, so Latour’s character contains multitudes.

I love when you write about Cather! What a wonderful post. I love that you're still attending to the ritual congregations of your former academic affiliation. :) There is transcendence to be found there! Death Comes for the Archbishop is such an incredible novel -- it's always seemed to me like a magic trick, that she wrote this novel that really has no plot, yet it draws you in so completely -- like life, like your own life, but not your own life. I think Cather's empathy for lower classes of people, especially women, had distinct limits. In "Old Mrs. Harris" there's a foot-washing scene where Mandy the "bound girl" (a slave the family brought with them from the deep south) washes Mrs. Harris's feet and Mrs. Harris gains comfort and has her dignity reinforced by the ritual of care, but the story as a whole is unconcerned to a fault with Mandy's mind, life, fate, future, etc. -- in a story about generations of women, we get more insight into the bothers' and husbands' lives and minds than we do into Mandy's. She was an astonishing artist. She was an analyst of magnificent insight who better-understood the life and mind of the creative than just about anyone. She is one of my absolute favorite writers. But yeah she had some sad (and very human) limits.

Fascinating article! Reading about neurotheology, I was reminded of Meghan O'Gieblyn's excellent book "God, Human, Animal, Machine" which goes even further: connecting not only religion and neuroscience research on cognition but also the long and strange saga of computer science and artificial intelligence. I did not realize how many of the metaphors and linguistic flairs used in computing trace from really out there Christian eschatology

PS: "It’s certainly true that listening to three panelists read their research aloud with no visual aids is sometimes stultifying." - I thought academic Death By PowerPoint was bad, listening to people read their work without an accompanying presentation sounds like a new circle of Hell was unlocked X_X