Sometimes while talking to former academics who have reinvented themselves as businesspeople, I feel like I’m looking at an M.C. Escher sketch. Everything in it makes sense until it doesn’t. And then those contradictions are all I can see.

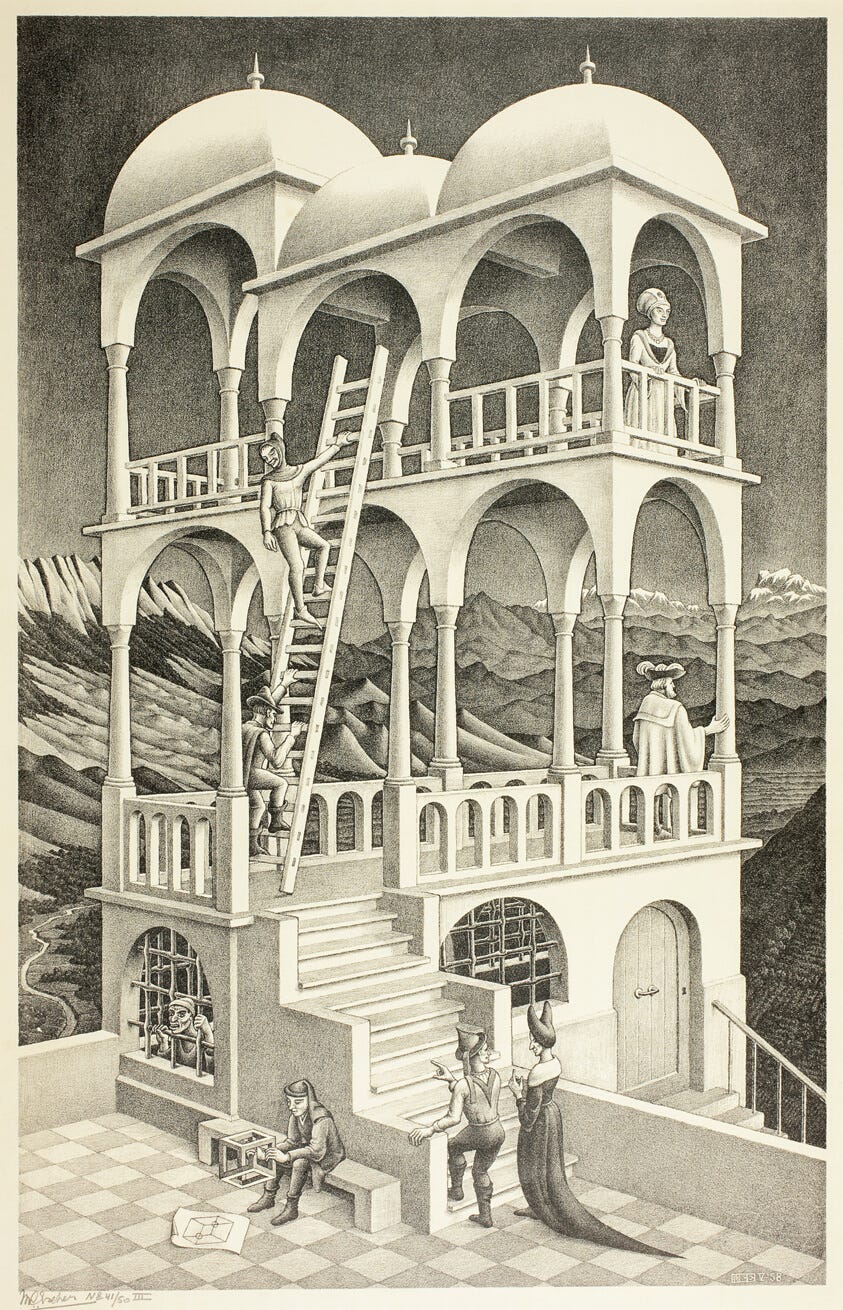

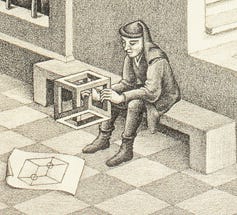

“Belvedere” captures the effect well, because it juxtaposes several people who seem content in their wonky world with a man who has constructed an impossible structure based on a Necker cube — and who seems to be the only one flummoxed by the result. There are still plenty of days when I feel like the man on that bench.

One thing I admire about

is that he owns these tensions in his path from academe to entrepreneurship. There is a refreshing honesty in his admission that, look, this isn’t the world he’d prefer to inhabit, but if it’s the only one available, he’ll find a way to survive within it. He’ll “feed the beast of growth” as a consultant, but also write a self-published book that indicts the very system that he’s learned to exploit.I asked, at the outset of our conversation, for your thoughts on how James reconciles these two strains of his work and intellectual life. Now that you’ve had a few days to digest the interview, what do you think?

I’ve been thinking about James’s story alongside Cather’s The Professor’s House, particularly Godfrey St. Peter’s recognition that making peace with modernity will require him to “live without delight.” The Professor sees the life he built for himself as a scholar, where his work was driven by pleasure and friendship, being replaced by transactional relationships and material culture. He falls into a malaise and very nearly asphyxiates himself (by accident?) with the gas stove that he uses to heat his cramped study. After his housekeeper rescues him, St. Peter tries to puzzle out his future.

All the afternoon he had sat there at the table…thinking over his life, trying to see where had made his mistake. Perhaps the mistake was merely in an attitude of mind. He had never learned to live without delight. And he would have to learn to, just as, in a Prohibition country, he supposed he would have to learn to live without sherry. Theoretically he knew that life is possible, may be even pleasant, without joy, without passionate griefs. But it had never occurred to him that he might have to live like that.

It’s possible that Cather overstates the case, that her own resistance to modernity was at times overwrought, but I can’t shake her notion that the world “broke in two” after WWI, and that she belonged to the “former half.” In fact, I am struck by how the paradigm shifts in our time seem to echo the ruptures of the early twentieth century.

Near the end of A Farewell to Arms, Ernest Hemingway writes:

The world breaks every one and afterward many are strong at the broken places. But those that will not break it kills. It kills the very good and the very gentle and the very brave impartially. If you are none of these you can be sure it will kill you too but there will be no special hurry.

James seems like one of those who has become strong at his own broken places. His last-ditch adaptation to capitalism has many affinities with the adjustments that modernity once required. Yet I also hear, in James’s forthcoming book, a desire for reviving some of what has been sacrificed to American individualism. In that way, he might also resemble Cather, who was as much a “recovering Romantic” as she was a modernist.

Cather never accepted the binary choice that Godfrey St. Peter saw for himself. She wrote her way out of that malaise. But for a time Cather struggled with the paradox of modernity, like Escher’s man with his impossible cube. Her answer to alienation was aesthetics — what Mark Doty calls “a religion of images.” And even though Cather was perhaps more of a New Yorker by the end of her life than she was a Nebraskan, she never was a pure individualist. Even her last novels are defined by the kinship that shaped her in an immigrant community. My mentor, Susan Rosowski, saw this as Cather’s “kinship ethic,” and it is a sensibility that pervades the Cather community.

Which brings me to another of James’s points. Did you agree with his premise that we need to forge bonds of “reciprocal obligation” with our neighbors to escape individualism? Is there a different term that you might use to capture the same principle? Is it possible to do that in the increasingly virtual spaces we inhabit, like LinkedIn and Zoom?

Subscribe to The Recovering Academic

Unlock more essays, interviews, and craft resources.

I think community is there for the taking, and while zoom is not as communal as in person, it's a big leap from commenting on Substack, which in turn is a big leap from the most pervasive social media sites.

I've zoomed with a few Substack writers in the UK who, absent the technology, I'd never have gotten to know. And we'll probably go to London this year, one of the drivers being the opportunity to meet whoever's around in real life. I realize that it's a privilege to pick up and make that trip, but it's an example of seeking out community.

I confess, Josh, I’m a bit overwhelmed by the enormity of the issues you raise here, both in the question about Hemingway that called me here and the one about community. One could write so much. Here, some partial, related responses.

First, I have to say I think Hemingway’s formulation, as gripping as it is, grips in the wrong place. We don’t get strong in the broken places. We get strong around them. The broken places heal but remain vulnerable.

I think another way of conceiving the adaptation to the world that is partly under discussion here is how we live with disappointment. The world, our lives, don’t deliver to us exactly what we hoped for, professionally, relationally, romantically, in community, in the prevailing culture and values – how do we live with that? How do we accommodate it? How do we create value in our lives – and we do have to create it ourselves – so that life feels worth living and a source of some fulfillment to us. Short of the tragic, that’s the hard work of living.

The creation part is essential. For every person who lamented the fragmented world of modernity and the loss of what they imagined a passing coherent spiritual and cultural world view, there was someone rushing headlong with enthusiasm into the revolutionary newness of that same modernity. I’m currently rereading Frank Kermode’s The Sense of an Ending in working on an essay I’ll publish next week. He writes about how that sense derives from our need to see and arrange order out of the disorderly flux of the world. But even that perception of disorderly flux, no less than the organizing narrative and theoretical arrangements and explanations we think to extract from it – some will argue – is time bound and standpoint determined. I venture to say that your relation to the idea, and need, for community differs from mine in ways we might stereotypically anticipate based on the different places we were raised in. My relation to a community of place (to condense complex experience and feelings into a simple formula) are shaped as much by Winesburg, Ohio as Grover's Corners, New Hampshire.