Episode 1 Transcript

Josh: I’m Joshua Doležal, and this is Catchment, the podcast for The Recovering Academic Substack series. My guest today is Dr. Kelly J. Baker.

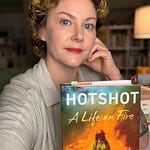

Kelly is the author of Grace Period, a memoir about leaving academe, and many other books including Sexism Ed: Essays on Gender and Labor in Academia, The Zombies Are Coming: The Realities of the Zombie Apocalypse in American Culture, and Final Girl, a collection of essays on grief, trauma, and mental illness. She also recently co-edited a book about post-academic life called Succeeding Outside of the Academy: Career Paths beyond the Humanities, Social Sciences, and STEM.

I found Kelly’s memoir shortly after I left academe, and so much of what she wrote about identity, sacrifice, and the pain of leaving a calling resonated with my own struggles. Whether you’re an ex-pat academic like us, still trying to keep your academic career afloat, or just a person who knows what it means to grieve and to heal, I know Kelly’s story will resonate with you.

This is the first episode of Catchment. I’ll release a new interview once a month, and while today’s podcast is free, the rest will be available only to paying subscribers. Your support allows me to offer my guests a modest stipend. It also gives you access to the full archive of essays and to private discussion threads on Fridays. You can upgrade your subscription at joshuadolezal dot substack dot com, slash subscribe, or just click on the button in the podcast transcript. If you can’t afford a paid subscription but want to stay engaged with this community, you can email me at dolezaljosh@gmail.com, and I’ll gift you access for a year, no questions asked.

Now, back to my conversation with Kelly Baker.

Josh: You were just saying that it took you 60,000 words to be OK after leaving academe and I don't know that I’ve reached that limit. I've written more than that I think over the past year on this newsletter. But thanks so much for joining me.

Kelly: Yeah, thanks for having me and it was probably over 60,000 to be honest with a lot of words and then a lot of words later too to kind of work my way through it since I feel like that recovering is a process. You're never quite done with it. I left academia in 2013 and there are still issues that I'm working out from then you know that pop up from time to time that are kind of surprising because so much of your identity is bound up in the Academy and I think that unraveling is really hard and a time consuming process.

Josh: So that was going to be my question: are you actually OK? Is there hope? It's been exactly a year for me. I don't know that I feel close to really being over that transition.

Kelly: I feel like that first year was really raw for me, really emotional. It took me a while to realize that what I was doing pretty actively was grieving and that I was really wounded and that I was trying to work through both of those without realizing that I was working through both of those and without identifying them. I was kind of flailing and couldn't kind of move past either of them without knowing what I was going through, so I was really a mess that first year. I was just trying to kind of figure out what does it mean if I'm not an academic anymore. What does it mean that I'm no longer going to try for this tenure track job that I've trained all these years for and that everybody that I was around thought that that's what I was supposed to be. And that was the only option. So what happens if that's not the option anymore and what do I have left? It was just really really messy and I just kind of felt like a free floating disaster. And I also had a brand new baby which didn't help any either, where I was trying to work out that identity and then work out the identity of having two kids instead of one and trying to manage that as well. So that first year I just don't know that there was anything near OK. I think there were just slivers and moments of OK that were not anywhere near where I am now. And I'm looking at like almost a decade now, and there's still these profound moments where I am like gosh I wish I was in a classroom. And then I really still grieve and mourn that identity in a way that I don't some of the others you know that are a part of what we call being an academic. But I feel like a couple years out I got to a point where there were other things I was doing that I was interested in and I was using the skill set that I had as an academic to do those things. So it didn't feel so much like I was abandoning that identity as much as I was refashioning it to use it for things that I wanted to do. And I think that reframing really helped me a lot actually to say I'm not giving this up. It's the stuff that I like about it —I'm holding on to that, I'm using that. And that I think eased some of the transition. So it wasn't so much I have to sever all ties, there are pieces of this that I can kind of carry on with me and really still enjoy. And then I can actually get rid of some of that stuff that I don't, and you don't have to hold on to it.

Josh: I want to kind of rewind… We're kind of starting at the end in typical postmodern nonlinear fashion. But you know back to the beginning because you said so much of academia is identity, and I wonder where you see that identity beginning. Why did you become an academic? What were the earliest sources of that and then eventually maybe we'll get to why religious studies.

Kelly: So I had this idea when I started college that I wanted to be a professor because I kind of knew I wanted to be a teacher but I wasn't sure I wanted to be a teacher of elementary school kids and I definitely didn't want to be a teacher of middle school. As someone that now lives with a middle schooler, legit decision. But I got in the college classroom and these professors they were amazing in these content areas they were in charge of and they knew all these things and they put together these narratives for us. Particularly in history and then American studies, which is what I got my undergraduate in, and then later in religious studies classes. Where they're talking about all this stuff that's so fascinating that I had no idea existed in the world. Or I had an inkling that it existed and these were people that dedicated their lives to it and they got to teach people about this stuff that seemed so cool every semester. So what I should say is that clearly I had this remarkably romanticized version of what a professor was. I just had this idea that being a professor was about teaching. And what I wanted to do was teach and be a part of this. Later as I got into a PhD program I realized that I was at a research one PhD program where it was more about research. Teaching was a thing that you did but often was an afterthought. It was still the thing that I loved. Don't get me wrong, I loved the research and the writing, too, just in different ways. I particularly like the writing piece of this and you know that's helped me as my career has progressed beyond the Academy. But getting into a PhD program is really different. Some of the shininess wore off when I realized that what you were doing is not kind of what I imagined professors were doing. So what I'll say is that there was some disenchantment right before I left the Academy. So I didn't leave the Academy with this kind of romantic ideal that I started with. Some of the shininess had worn off and worn off and worn off to the point where I was like I'm not sure I can do this anymore because this is not at all what I was imagining it was gonna be.

Josh: That's part of the trauma of the transition, isn't it? The trauma of the transition is losing what really begins as a kind of idealism about yourself and your identity and who you can be in the world.

Kelly: One of the things that I thought about a lot in that transition is that the way you imagine our lives are going to be, it completely ignores how wildly chaotic life is and that it hardly ever works in the ways that we want it to for lots of reasons.

Josh: We started your story in college, and I'm wondering…were you a first generation student? Did you have any sort of role models that you were following? Did you have a religious background that predisposed you to that particular kind of research?

Kelly: I was a First Gen student, so for me college professor was one of those things where I was like you just go through college and then you get a PhD right like that's the thing you do without any understanding of what the apparatus of that was. Because I had colleagues in Graduate School whose parents were professors so they kind of understood how to maneuver about in a way where everything was kind of culture shock to me, where I just didn't even know how to manage Graduate School and had to learn pretty quickly how to figure that out. I didn't come from a particularly religious background. We were sort of that kind of culturally Christian that exists in the South, where you bless food and you might go to church, and I had church going relatives that were more churchy, you know depending on where they went. My mom grew up religious in a particularly conservative religious background and so was a little bit more skeptical towards it and then as I ended high school went back to an adjacent Christian Church to what she'd grown up with and so that was kind of a surprise to me and something that I kind of had to manage. And it was part of what I was intrigued by: oh why is someone interested in this, what draws someone to this, what's going on here and and how do I figure it out. I think that figuring it out piece is how I ended up in religious studies. I was like oh this is really fascinating. And as I tell people all the time I don't like have a horse in a race. A lot of times folks are coming from confessional backgrounds or are looking at their own traditions, and for me it's like no I'm just fascinated by humans and what humans do. And for me religion is one of those things that humans do that is ultimately fascinating and the more you dig in the more fascinating it gets. And in a lot of ways it's so unpredictable that I just…like this is how I ended up studying people that are like the zombie apocalypse could be real, and I'm like tell me more. Like let's go, you know. And then other paths to think about how white supremacists are involved in Christianity and how these work together. So that is one of those things where questions lead to more questions for me and religious studies really just allowed me to do that in a way that I probably could have done in other fields too but there was just something that drew me in there.

Josh: So you did all the things right. You got the book contract and were out there doing what you're supposed to do for job applications and interviews. And what happened?

Kelly: I had the good fortune to graduate in 2008 when the labor market and the humanities really kind of collapsed. Before I finished my PhD, those first couple of years, I had interviews. I was really good at coming in second. I felt like I was particularly talented at that. But then the market dropped out and so you know it's one of those things where people are like there are no jobs and in my particular sub-discipline, which is American religious history, we had years where there were literally zero jobs. There was nothing to be had or there were one or two but then the sub-specialization within the specialization was not something that matched what I did. And you know to be fair to search committees, I worked on white Christian nationalism before that was a thing and sort of popular like it is now so that in 2008 through 2011, it was a head scratcher. Why would you work on this? Whereas now I think people mostly get it. I just applied and got interviews and it just didn't go anywhere. There's a couple things going on there. One, I was pretty upfront about the fact that I was married and there were some interesting gender dynamic things going on there. I've written about this some, about how search committees reacted to that – not well. Part of this was I made a decision that I was unwilling to leave my then toddler child and my husband to go to a visiting position for a year. Maybe that would have helped me, who knows. But I ended up in lecturer positions, these contingent renewal semester or once a year kind of positions. I was married to another academic, which also complicated the story.

Josh: Was that part of why search committees reacted, because there were spousal hire issues?