Episode 4 Transcript

Joshua Doležal

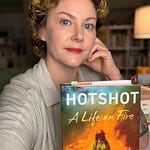

I’m Joshua Doležal, and this is Catchment, the podcast for The Recovering Academic Substack series. My guest today is Dr. Liz Haswell.

Liz is the first scientist that I’ve interviewed, and she is also the first guest on this program who is preparing, right now, to leave academe. After she turns in grades for the spring semester, Liz will cross that Rubicon. We spoke about everything that led up to that hard decision, as well as what she hopes to find on the other side. Like many of us who have shed our academic robes and the titles that went with them, Liz is hoping to rediscover herself.

Liz Haswell

I would really like to untangle what parts of my personality and my experience this far in my life are parts of me and what are parts that I took on because they helped me be successful, because they made things easier in this big complex that we call academia.

Joshua Doležal

Liz Haswell is Professor of Biology and Howard Hughes Medical Institute-Simons Faculty Scholar at Washington University in St. Louis. She co-hosts a podcast called The Taproot and later today will be launching her own Substack — Unprofessoring — a newsletter about consciously uncoupling from the ivory tower. When I first read her faculty profile and CV at Wash U, I was shocked that she was planning to resign tenure, seemingly at the top of her game. Liz has her own lab, works in STEM — which seems to be getting all the funding and promotion these days — and has been publishing and winning awards at an impressive rate. All of those things will soon shift into the past tense. Why would she give it all up?

This is the fourth episode of Catchment. Today, in addition to the full episode for paying subscribers, I’m sharing a free sample of my conversation with Liz. To hear the full interview, you can upgrade your subscription at Joshuauadolezal dot substack dot com, slash subscribe. Or just click on the subscribe button in the podcast transcript. Your support allows me to pay my podcast guests a modest stipend. It also gives you access to my full archive and subscriber-only content, like stories for The Chronicle, private discussion threads on Fridays, and literary work that I share throughout the year. I look forward to welcoming you to The Recovering Academic community.

Now back to my conversation with Liz Haswell.

Joshua Doležal

Maybe we can go back to the beginning a little bit and think about why you became an academic, if you had any mentors or family influences or you know when did that story begin for you?

Elizabeth Haswell

Right, actually it began pretty abruptly, so I do come from an academic family like so many of us do. My dad is an English professor. He was an English composition professor at Washington State University for a long time and then moved to Texas A & M Corpus Christi. He's now retired and my mother was a Spanish instructor, so I had these, you know, I grew up in Pullman, WA, which is a small college town, and half of my classmates were the kids of academics and half were the kids of farmers. It was a pretty cool place to grow up actually. But in my early teens I was pretty convinced that I was not smart. I mean, I have diary entries that are just pages of…I'm not into school. I'm not smart. I'm not academic. And my parents want me to be this way, but I'm just not into it. I just want to be an interior decorator. I mean I was really insistent that what my family did was not for me. And then I took Biology my second year of high school. I mean, it was like almost instantaneous that I was like, oh, actually this is what I want to do. And I have this such a vivid memory of having done all the reading because I was a very good student, even though I was saying I wasn’t. Having read about all the different parts of the plant leaf. So if you look at a cross section of a plant leaf there are all these different types of cells in there and they’re organized in this very stereotypic way, and that, you know, reflects their function within the leaf. And so I had read about it and then went into school, and we looked at a slide under the microscope of a cross section of the leaf and it looked exactly like what I'd seen in the textbook. There's something about seeing in real life something I'd read about in a book that just captured me. And so from then on, I mean, I have like drawings. I did, you know, like little cartoons I drew with my friends in high school that all had me drawn as a chemistry professor. And then once I got to, you know, then I worked in a lab. I think the summer after I graduated from college, I worked in a lab and I was, like, completely smitten. And so that was all I ever wanted to do. There was really no question.

Joshua Doležal

So it sounds like a conversion experience.

Elizabeth Haswell

I'm wary of sort of feeding into this myth about scientists and how the successful ones always knew what they wanted to do and never had any doubt. And if you do have a doubt, then you're probably not meant to be a scientist…because that's totally wrong. And it's also totally fine to be a scientist or an academic because it's a job, and this whole, like science as a calling stuff is, I think can be very toxic. So I just wanted to put in a pitch there for this is my story, but it's not a blueprint for anybody else's success.

Joshua Doležal

Well, and as I've written, I mean my Substack began with a post titled “The Calling.” Where I'm questioning this very thing—the singular calling that becomes the one thing you were born to do. And it really does create an existential crisis if, you know you can't do that thing anymore or you know, how do you fill that identity void if that's taken away.

Elizabeth Haswell

Exactly, that's exactly what I'm like struggling with in a big way right now, for sure.

Joshua Doležal

Well, I think we started around the same time. So you I think were four or five years ahead of me. But the main difference was that I went straight into a tenure track after the PhD and you had this limbo of seven years of postdoc. So nearly a decade you were what we think of as contingent, or you're a contingent researcher, I assume, or a teacher for that time.

Elizabeth Haswell

It's all research. So in the life sciences, once you get your Ph.D. you're not ready to run your own research program. Typically there are exceptions to that rule, but for the most part then you head off into these postdoctoral positions where you are meant to be building your independent research program. You know those used to be one or two years, maybe three, but over the last 20 years or so, those positions have become these sort of holding patterns where people accumulate more and more publications and they get more and more experience as they wait for those tenure track landing positions you know. And so I was switching fields, not fields like biology to chemistry, but I had done my undergrad and my PhD work in one area of biology and then moved to plant science as a post doctoral researcher. And so I spent a lot of those early years just like figuring out what I was doing, I didn't know what I was doing and it took me a while to figure that out. And then it took me… I actually did job searches for three years before I found a tenure track position. Yeah, those years kind of sucked. Those latter ones were pretty painful, but.

Joshua Doležal

Well, and some people go through seven or eight years or more of that same cycle. So you know it can be a truly brutal, just soul crushing kind of thing. I mean my first year on the market, I applied… And we call it being on the market, which is so crass, isn't it?

Elizabeth Haswell

It's grody, right?

Joshua Doležal

I mean, it's just an awful way of thinking about it and for us, the Modern Language Association would meet once a year around Christmas time, which is even more humane, for the job interviews and they would rent this giant conference hall and we called it the meat market, you know, because we were just slabs of meat waiting to be, butchered or I don't know, we felt commodified, I guess, was the other way of thinking about it. So I applied to 95 positions before I got a single interview and then it was a wave of, you know, visiting positions in the spring that finally got me to where I landed, but yeah, you just spend so many years feeling like you are an overachiever. You're at the top of your field, you've been distinguished as an undergraduate. You've hit all of the extrinsic markers of success. And then suddenly you're completely invisible. How did you deal with that?

Elizabeth Haswell

It was really hard and it was. I remember feeling like powerful in the sense that I had finally gotten together this research program that I knew would be successful. Like I knew I could do it and I had so many ideas. And I had also, I should say, very prestigious institutions in my CV. I had worked with very famous people. And so I had, for the most part, a very solid CV. But then I applied I think the year I was successful, I applied to seven places. So that's like how many jobs there were for plant biologists in R-1 institutions that year: seven. And so it's all of the same people interviewing like the same five people. Who are you know, coming out of the labs that everybody knows the name of interviewing all those places and then whether you're successful, it's partly in your hands because you know you could do a bad interview or whatever. But some of it is so random and has to do with the nature of the people on the search committee or one thing you might have said to one person that then blackballs you or makes you the one they want to hire, and the sort of randomness of it, I think, was the part that messed with my mind the most where there was just this whole aspect that I couldn't control. And I hated that.

Joshua Doležal

Well, so you had seven years of that and three of them were on the job market and... We were talking earlier about the term hidden curriculum, which is something that physicians use for their training – they have this external curriculum or, the official curriculum, which often includes some sort of gratuitous humanities training or something that's supposed to signal that the patients are first or humanity is really at the core. But the hidden curriculum is the real teaching that happens indirectly through actions, through watching what mentors do, what they prioritize, what they can communicate silently is the most important thing. And that's often not the patient, not humanity. So what was the hidden curriculum of teaching and research for you during those post doctoral years? And I guess we could carry that into your faculty work now, since you're kind of nearing the end of that.

Elizabeth Haswell

Yeah, I mean, there's so much of this out there and I think that's where I had the benefit of coming up in an academic family is that a lot of that information was sort of part of my upbringing. But also you learn it so like as a postdoc, you really ought to. I mean, I'm not saying this as if it's real, but I'm saying these are the lessons I absorbed were… You ought not to express interest in any career other than an academic career, if that's the direction you want to go. So expressing uncertainty is bad. You have to have teaching in the right sort of gray space like you can't say I hate teaching, but you also can't be too serious about it because you really need to be serious about your research. This is for like the R1 type of position. I think that those were lessons I learned pretty well, although the teaching part, I've never really gotten over. Actually, I'm not a great teacher and I don't love it, and that's expressing that has been something that, like I've been told many times, it's like not OK. You really have to say that you like teaching, even if you really don't. And then those are sort of the bigger things. But I feel like I, need to dig more into like what are even more deep lessons that I internalized about even what sorts of hobbies were OK to have? So, like during my postdoc, I got really into and I'm still. I'm like, embarrassed to tell you this, but I'm going to say it. I got really into embroidery. Right. And so. But like why am I embarrassed to say that because that's not the right kind of hobby for a serious scientist, right, serious scientists should have hobbies like rock climbing or marathon running. Reading statistics books and your free time, whatever. So I hid that. I still hide that. Like, I don't think there's very many people who even know how much time I spend, like doing cross stitch. So those kinds of things I pushed down or didn't even let myself be interested in things that I knew… At least nobody said to me like serious scientists don't do cross stitch, but I just bought it.

Joshua Doležal

So is that true also of women scientists? I mean the things that you've described sound like a kind of machismo which I would associate with. Science is a kind of patriarchal structure, but would would you say that women who are in science seem to manifest that kind of ultra marathon or persona or…?

Elizabeth Haswell

I'm not sure. And I certainly couldn't speak for anybody else. And of course I should say I do know people more and more now, especially the young folks coming up who are perfectly comfortable talking about their pottery or their art or whatever they do. Without any of the sort of hang ups that I think I absorbed.