I’ve been watching colleagues post their back-to-school updates for a few weeks now, some holding signs showing how many years they have been teaching (over 40 years, in some cases), others wearing spiffy first-day outfits, some posing with their kids, as I once did, when we were all heading out together to our classrooms. There has also been plenty of venting about syllabi, fussing with course software, and enduring those soul-draining “workshops” where an administrator reads for a few hours from a PowerPoint that could just as easily have been an email attachment. Feeling all this is like a twist cone: wistfulness for what I’ve left behind entwined with gratitude for the life I have now.

Nearly seven months have passed since I walked away from my job, and as the planet spins back toward fall it seems time for an update on career and identity.

If you are new to this series, you might enjoy my essay on the dangers of claiming a single life calling, this riff on how to stay true to yourself in a numbers-obsessed world, and a more recent meditation on grieving. Each of these marks a milestone in my journey.

One of the hardest parts of this transition for me was exchanging a career with a title and salary for one with less obvious trappings of success. I was raised in rural Montana, where a man without a job is less than nothing. At my age, nearly 47, these mental grooves are hard to escape. As Elizabeth Proctor tells her husband John in The Crucible, “I do not judge you. The magistrate sits in your heart that judges you.” It is remarkable to see, even after a few months, how much of the turmoil I felt this spring — which was real enough — stemmed from how I felt about myself, not necessarily how others regarded me.

“What do you do?” is still not my favorite question. But it’s getting easier to say, simply, that I am a writer. Should anyone probe a little further, I mention this Substack, the work I’ve been doing for The Chronicle of Higher Education, and the literary projects I’m still shopping around. But I typically go on to explain that all of this fits into a better life for our family than my old career allowed.

My children now have the same chance I did to see their grandparents nearly every week, to hang out with their cousin at the pool and build relationships with their aunt and uncle beyond the drive-by holiday greetings. When I was teaching full-time, I couldn’t (or did not feel that I could) cancel all of my classes and afternoon meetings to stay home with a sick kid. That was unfair. My wife now has more space to grow her business, which Dylan Dreyer, of The Today Show, agrees is awesome. I’m also not spending eight hours behind a shut door on the weekends grading papers or prepping classes.

Flexibility is a privilege. But the highest earners in America typically work 60-80 hours a week, so even those with more options do not always choose personal freedom. Claiming a better life required me to stop thinking of professional success as detached from or in competition with my identity as a husband and father. I don’t need to absent myself, as I’ve seen many men do, to feel purposeful. I prefer Liz Fosslien’s measure of success, though I think many of us with children would substitute “availability to my kids” for that large slice of free time.

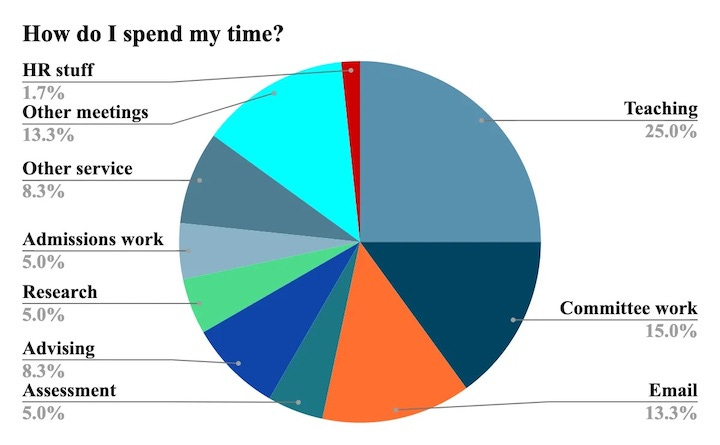

It can also be a useful exercise to draw a pie for how you’re spending your time. How much of your why do you see in your workday? Everyone has a different threshold for this, but when I realized that maybe 30% of how I was spending my time as a professor represented the reasons I originally chose the profession, that was a reality check. This chart is a rough guess, but it shows how deeply most faculty feel Thoreau’s dictum, "Our life is frittered away by detail. Simplify, simplify, simplify!”

A few years ago, Cal Newport published an essay in The Chronicle with the self-explanatory title, “Is Email Making Professors Stupid?” Well, yeah. And so is committee work, assessment, and everything else I list in the pie above. It’s like trying to talk to my wife at dinnertime with the kids running around. As soon as one of us opens our mouth, someone is fighting in the next room or running into the kitchen to shout over us. Scholarship and innovative teaching require unbroken time and attention. Right now I feel a little scattered for spreading my attention across four creative projects at the same time, but that is infinitely better than where I was last year.

I was about to say that no one asked me, but as it happens several people have asked me over the last few months what advice I might offer to anyone contemplating a change in careers. Here are three things that I wish I’d known back in January.

Own and interrogate your burnout:

If you’re thinking about career and identity, chances are good that you fall somewhere on the burnout scale. If you want a diagnosis, you can try something like the Maslach Burnout Inventory, which measures emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and personal accomplishment. Or, if you are like me, you might prefer a book or a podcast.

Emily and Amelia Nagoski offer a feminist take on burnout that I find enlightening. Their first three chapters, in particular, have helped me think about how the stress that I’ve carried with me for decades from my fundamentalist upbringing and my socialization as a Western man diminished my resilience in academe and intensified the anxiety I felt after walking away. It is a revelation to consider that self-care is really a survival mentality, the kind that once made me get up at 5 a.m. to go for a brisk run in the dark, so I could ride the serotonin wave throughout the day. Instead, we ought to aspire to care, which we enjoy from a nurturing family and community.

If you don’t have time for the book, you might find their podcast a helpful companion. Listen as they discuss how to separate stress from the stressor, complete the stress response cycle, and more.

Jonathan Malesic made a splash with The End of Burnout earlier this year. I have argued with some of his conclusions in this series, particularly his notion that lowering expectations for one’s work is preferable to idealism because it guards against disillusionment. My journey has led me to embrace my idealism rather than distancing myself from it, but I appreciate Malesic’s scholarly take on work saints and work martyrs in American culture. He is honest about his reasons for leaving academe, and he writes about work and identity with real historical depth.

Malesic lists several podcast interviews on his website, but here’s one that I think captures the heart of his book.

I owe a debt to Bruce Feiler. My friend Evelyn recommended his Life Is in the Transitions a little over a year ago, and I’ve kept coming back to it. Feiler has helped me see that there’s no such thing as a single midlife crisis. We all experience ground-shaking disruptions — lifequakes — multiple times throughout our lives, and the pace of change is increasing. Feiler says this is because the linear life is dead: “the idea that we’re going to have one job, one relationship, one home, one spirituality, one source of happiness — that’s gone. It’s been replaced by a nonlinear life with many more twists and turns.” Feiler has interviewed hundreds of people about their major life transitions and identifies best practices for navigating the “messy middle” purposefully.

Feiler can get a little windy, but he is at his best when speaking extemporaneously on podcasts such as this one.

What books or resources have been helpful to you during your career transition? I’d love to know in the comments or in reply to this message.

Complete the grief cycle:

I am no expert on grief, but my own lifequake was preceded by three deaths. My grandfather died in January, 2021, and my grandmother followed him last August. I was moistening her lips with a swab when she drew her last breath and then fought for another that never came. Two months later, one of my cousins — 40 years old and mother to seven children — died of Covid-19.

I was less blindsided by my last day on campus, but it would be no overstatement to say that the finality of leaving my office felt like another funeral. I took photos of sentimental things — my name plate on the wall, my name on the landline Caller ID — as if gathering proof that I’d really worked there, that I wasn’t dead yet. I felt like Ted Kooser did when he opened the newspaper one morning and saw that there had been a murder at an apartment where he’d lived with his first wife and their son. His essay “Small Rooms in Time” is a meditation on how we carry these remembered places within us like the miniature rooms in a dollhouse. Kooser felt that the murder had stained his memories of that place, that there was no way to reclaim the innocence and safety he’d once felt there: “It has been more than thirty years since we lived at 2820 ‘R’ Street, Lincoln, Nebraska. I write out the full address as if to fasten it down with stakes and ropes against the violence of time.”

Room 216 in Jordan Hall on the Central College campus in Pella, Iowa, will never be mine again, and to some extent the violence of that last goodbye still haunts me. Like the apartment that Kooser could only remember with bloodstains on the wall after reading of the murder there, my office mostly sits vacant in my memory. I had hundreds of meaningful conversations with students there over the years, including a standing lunch meeting with a student during my final semester. He came to me after our first class and mostly just wanted to talk about life. We spent many hours in my office thinking out loud about fathers and sons, inherited trauma, how to forgive friends who ghost you, and more. I can still picture him sitting there on my couch, a basketball player who towered over me when we stood to shake hands. But we both knew it was temporary, and so an icy wind blows through those memories.

Anyone who cares deeply about their work will grieve it when it’s gone. There is no rushing grief, and in some ways it’s never done. What we need most while grieving is someone to hold that space with us. There’s nothing to fix. The cycle must run its course. Two women I know were fortunate to have partners who allowed them to weep after leaving their jobs, sometimes while curled on the couch, until the weeping was done. My own hurt manifests more in storytelling, in the need to be heard. The times I’ve felt most alone have been when someone has seemed embarrassed by how I was feeling or has tried to hurry the grieving along by proposing things I must do to move forward.

I’m better than I was in February or March of this year. But grief sneaks back up on me from time to time. My grandmother’s headstone was just installed last week (supply chain bottlenecks affect everything), and my mother and aunt sent photos of it on the same day that friends were posting about their first day back at Central College. I remembered how angry I was that my grandmother’s pastor gave fundamentally the same eulogy for her that he had for my grandfather just seven months prior, how much I chafed against the generic story of heaven, which felt like it erased my grandparents’ real lives more than it honored them. Just so, there is no universal balm for any of us who have suffered loss. If we loved a person or a profession deeply, death ought to sting. That is the point. Find people who will hold that hurt with you as long as it takes.

Build a new community:

Many of you already belong to The Professor Is Out, the most robust community I know for recovering academics. After a long hiatus from Facebook, I’m finding that reconnecting with people, even if I’m only watching their lives from afar, is grounding.

But we can’t live by tweet alone. The most significant shift in my journey came this summer, when I participated in a month-long writing workshop in Prague. If you are new to this series, I explain the impact of that experience here. American culture trivializes the arts, and it was transformative to live in a place where beauty was a basic fact of life. Sitting around a workshop table with fellow writers and steeping myself in the power of story will sustain me for some time to come.

Another unexpected reward from that trip was the sense of coming home to Pennsylvania. When we moved last winter, I left our Iowa home for a place that was not yet mine. But home is the place you come back to, the anchor to which you return. There was a ceremonial closure in flying back across the Atlantic, driving four hours from Newark to State College, and embracing my wife and my children as they ran into my arms.

Expanding my tribe where I live is the next challenge. One of my goals for the year is to find ways to replicate the many conversations I had in Prague, where the talk and the beer both drew from a bottomless well.

Thanks to your support, I am now approaching the point at which it might make sense to add paid content to The Recovering Academic. Over the next few months, as I plan the future of this series, I’d be grateful for your feedback on topics that you’d like to see covered more deeply or new features that you’d like to see added. If you’d like to make suggestions, please complete this Google Form. Or you can always send me a note at dolezaljosh@gmail.com.

Excellent article. Burnout is real. I left a stressful job last year for another job, but at a school (K-12) that is much smaller, fewer students. Also, a rural commute, not one on a busy freeway like my previous position, where I would enter school already stressed from the drive.

I'm surprised how many people aren't aware of burnout and just grind through it. I used to be like that, too. It's not healthy, mentally or physically.

Yes, I like how Joshua addressed the emotional aspect of working. The last couple jobs I left I was tearful for the good times I had. Nevertheless, each move was a good one.

I actually enjoy work, being around people, and seeing a job well done. I just can no longer do it in stressful environments.

The only advice I give to those living with grief is to do whatever non-harmful things it takes to find comfort and perhaps even hopefulness. The people who love us will still love us, no matter what we do. Just for myself, I have found that grief can slowly excise some of the worst or needless parts of us.

On the topic of burn-out, I come from the perspective of being in a family that for hundreds of years has been one of small business owners, primarily farmers. Within those multi-generational small businesses everyone had a role to play in family survival and there was - is - no such thing as "work life." There is simply "life." Most farmers and many small business people feel a sense of purpose, and in some cases even feel a noble calling. The land owns them. If they lose their farms they might give up their lives.

I imagine burn out happens when people do not have much control over their work lives. I tell my wife that my boss is a jackass, but at least my boss (me) can't fire me.