For many months now I’ve been wrestling with what I mean by the term “recovering academic.” The phrase is a common wisecrack in the post-academe crowd, and it might seem glib to those who are recovering from addiction. But I don’t actually mean it as a joke. Becoming a professional academic requires an overhaul of your brain reward system. Those of us who leave the profession often feel that we’ve lost touch with what’s actually good for us. The things that consume us, that we can’t get enough of, come with significant tradeoffs. And all too often the payoff pales in comparison to the pain.

As I wrote in an earlier post, it’s possible for some to rewire that reward system without leaving academe. And some of us who have left discover that it wasn’t the teaching or the writing that we needed distance from so much as the environments where we practiced our craft: the institutions or professional organizations whose definitions of mastery and purpose ultimately proved incompatible with our own.

Throughout the months I’ve spent in recovery, I’ve identified a lot of unhealthy patterns in how I thought about my former job. I don’t expect that I’ll ever abandon those mental grooves entirely. For instance, I’m always going to be a blue-collar kid from Montana who equates hard work with self worth and thinks he has something to prove. I’ll never forget the time during my senior year in college when I set up a meeting with a professor at Emory University to talk about the graduate program in literature. I was visiting relatives near Atlanta for Thanksgiving, and my cousin, who was working construction at the time, gave me a ride to campus. The professor was waiting for me outside his office building, and when we pulled up in my cousin’s truck I could see the professor’s expression change. He still invited me in, but he’d seen enough, in his mind, to know that I didn’t belong at Emory, and his advice was all about how to find a master’s program that would allow me to trade up. Strategic advice, no doubt, but illustrative of how academic prestige often rests more on privilege-based perception than on aptitude or merit.

I wouldn’t say that my whole career was an attempt to prove that guy wrong. But part of it was. And that was a betrayal of myself. An important part of my recovery has been trying to decouple my work ethic from status markers that mean nothing outside the ivory tower and that have little intrinsic worth. Many academic resumes can be seen, outside the profession, the way that Leo Tolstoy characterizes the life of Ivan Ilyich: as “most simple and ordinary and most terrible.” Ilyich didn’t see it that way when he was striving for the next ministerial post, angling for a higher income, or lording his judicial power over defendants. But the hollowness of those aspirations was exposed when Ilyich fell ill and began to wonder if he’d lived the wrong life. A scholar I interviewed recently for The Chronicle of Higher Education said she felt something like rage after assembling her portfolio for tenure: seeing how much she had done and knowing how small the reward really was. It’s like trying to please a parent who will never say, without an ulterior motive, that they’re proud of you. Recognizing that futility is simple enough, but it’s much harder to really believe that your personal standards for success are the only ones that matter.

How easy it would be for my writing life to fall into the same grooves that my years in academe have carved. I thought about this in June, when I learned that The Missouri Review had accepted one of my essays. The Missouri Review accepts less than one percent of submissions. I’ve been trying to publish with them for more than twenty years. It’s the kind of venue where an agent might find me, a potential springboard to bigger platforms like the Best American series. But is that why I’m really writing? To get an agent? To make it into a national anthology? Those are the wrong whys.

I write to wrestle with problems that others share, to build a bridge between my restless mind and a reader’s. I am partial to Emerson’s notion that we are half ourselves and half our expressions, that writing reveals us to ourselves. It might seem quaint or flat wrong by today’s standards, but I strive as a writer to be representative of and in conversation with readers who don’t look like me or share my background. Unlocking a new part of my understanding matters most if it accomplishes the same for you. I must remind myself of this: that my writing life will only allow me to recover from academe if I abandon the path that keeps forking off toward self-aggrandizement, pretense, and other dead-ends. Recovery means stepping back onto the course that leads toward connection, community, and real belonging.

Sometimes that restorative path leads directly away from my writing table. Earlier this year I wrote about rituals that might help navigate the “messy middle” of a major life transition. But I’m nearing the end of that stage, happily, and now it’s time to think with a longer view.

I am not a religious person, but I prefer a ceremonial life, and many of the ceremonies that matter most to me are built around food. Robin Wall Kimmerer captures the idea in her essay on the honorable harvest, or the lifeway that centers eating on gratitude and reciprocity. It is not possible to practice the honorable harvest and regard gardening as a hobby. The contemporary definition of “hobby” derives literally from child’s play: from the antiquated hobby horse. Which is why many describe a new set of golf clubs as a toy. The “why” of a hobby is more like “why not?” By contrast, I see gardening as a practice that connects me to family, to history, and to the place I live.

A friend introduced me to maple sugaring when we lived in Iowa. We had a large Norway maple in our front lawn, and syruping season became an annual ritual for our family. In a recent essay for Fourth Genre, I reflect on the natural and cultural history of maple syrup, how a tradition built on reciprocity is being threatened by mass production. Tapping a tree and boiling the sap down to syrup is more than a selfish act. It is a way of checking in with the place, paying attention to the health of the trees, tracking the shift from winter to spring. If the sap flows the way it should, I know that the natural cycles are still working and the lifeblood of the forest is surging back up from the roots.

I was delighted to find two trees on our property after we moved last year, and the sugaring ritual helped me start thinking of the place as home. You have to watch the evaporating pan so it doesn’t burn, and that means spending a few hours on the patio, where time slows down and you daydream a little and then rouse yourself to lean into the steam that billows around your face, warming the tip of your nose as you breathe in that first hint of sugar. When the liquid turns gold and drips from your wooden spoon in a sheet, it’s ready to bottle. In our house we say “Thank you, maple tree” every time we pour a little of that homegrown sugar. As Kimmerer suggests, we ought to be saying thanks to everything we lift to our lips.

I’m thinking about this now because I’m planning a garden for next year which will require a substantial deer fence. The neighborhood where we live has a large wooded commons where many deer from the nearby game lands take refuge. The lack of predators or hunting on private property has allowed the herd to grow considerably, and a recent survey of the forested commons found that the deer are eating the native seedlings and allowing invasive plants to take over, which means that the forest has lost its ability to regenerate itself.

So my garden planning has begun with the grim knowledge that the place I inhabit is out of whack. “Just as a deer herd lives in mortal fear of its wolves,” Aldo Leopold writes, “so does a mountain live in mortal fear of its deer.” I can’t do much about the deer unless I convince the neighbors to allow me to hunt them with a crossbow. But the deer problem has allowed me to avoid tilting the ecology of my acres even further out of balance.

The field where I’ll lay out my garden is a prairie meadow that the previous owner planted with many flowering plants. We’ve learned that we have Indian hemp growing there, as well as goldenrod, coneflowers, and Maximilian sunflower. I’m an admirer of Bill McKibben and Novella Carpenter, two nature writers who feature honeybees prominently in their work, and so I’d thought that adding beehives would benefit both the plants in our meadow and the vegetables that I’d like to grow.

When I crowed about some of these plans on Facebook recently, I tagged fellow Nebraska alum Benjamin Vogt, an expert in prairie restoration, thinking that he might approve. Instead, he asked, “Why are you raising honeybees?” A very Socratic response that made me much more receptive to reconsidering my view than a frontal attack would have. Benjamin pointed me to one of his posts on the subject, which I find eminently persuasive. I knew that honeybees were not native to North America (or were reintroduced by Europeans long after they had died out), but I had not understood the extent to which they compete with native insects, introduce disease, and disrupt “co-evolved pollinator networks,” thereby diminishing seed production for native plants. These dangers are magnified if domesticated bees swarm, which would be a distinct possibility in our wooded commons. Even my notion that honeybees might increase vegetable production in my garden turned out to be wrong, or only partially true. I should have known: native bees do it better.

So as I’m setting the posts for my garden fence, thinking about the cucumbers and snap beans and heirloom beets I plan to grow next year, I’ll be thanking Benjamin for steering me straight. I’ll also say a word of thanks to the bees that are already here. Building this garden will require some taking: lumber and fencing materials, a truckload of black dirt, mowing some flowering plants to make room for my beds. But I know that a garden has a lot to give back in reduced fossil fuel dependency, in composting our food waste, and in children who learn, while eating cherry tomatoes straight from the vine or drizzling syrup on their pancakes, that the earth loves them, and that they ought to do their best to love it back.

What rituals help you heal? How do you interpret the honorable harvest in your own life? Let me know in the comments.

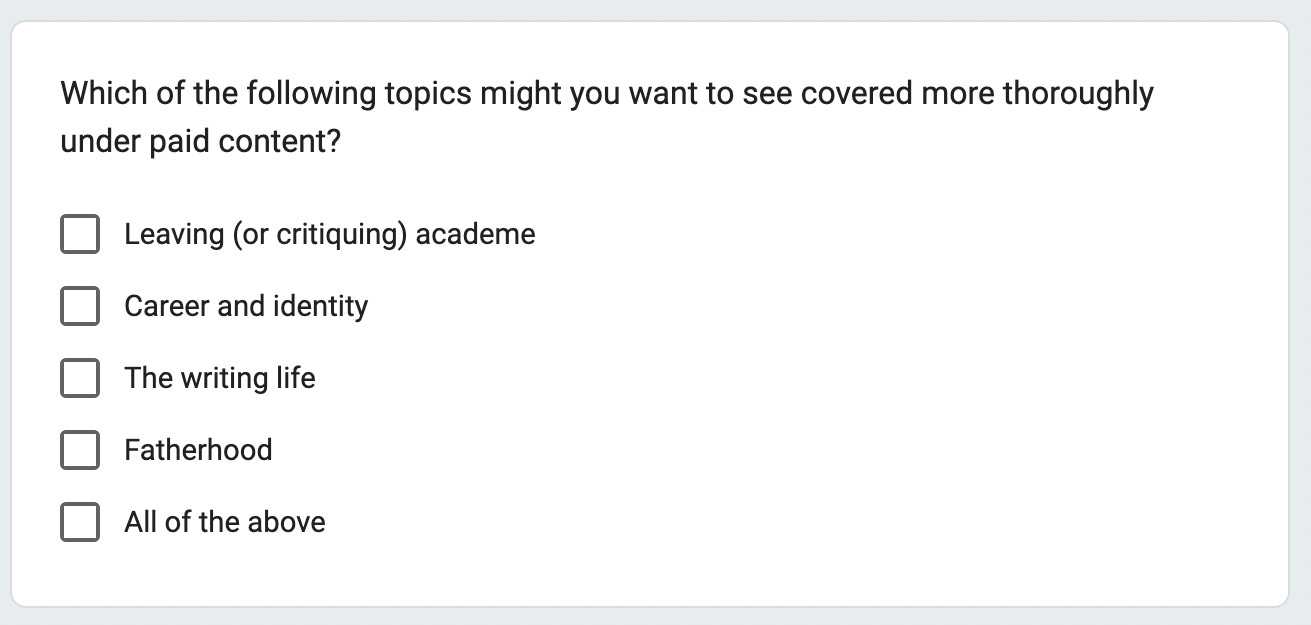

Thanks to your support, I am now approaching the point at which it might make sense to add paid content to The Recovering Academic. Over the next few months, as I plan the future of this series, I’d be grateful for your feedback on topics that you’d like to see covered more deeply or new features that you’d like to see added. If you’d like to make suggestions, please complete this Google Form. Or you can always send me a note at dolezaljosh@gmail.com.

Thank you, Maple tree 🙏🧡 Yes. Anything that makes us slow down and redirect our attention to gratitude is a healthy, good, and healing ritual.

Are you familiar with Wendell Berry? Im sure you must be. The Mad Farmer Liberation Front.... make more tracks in the snow than necessary... when they have captured your mind, lose it. Practice resurrection. 🔆

Thanks!!In the second paragraph, you refer to an earlier post on the topic of reward systems. I’m curious about that too.