For much of this year I’ve been writing about what’s wrong with academe: why I left, why others are leaving, even why the current state of higher education reminds me of Czechoslovakia under Soviet rule. A sharp-edged critique has its place, but as the famous composition theorist Peter Elbow once wrote, it’s best to balance believing and doubting.

I often told students in creative writing workshops that giving good feedback on a draft is excellent preparation for marriage. Most writers and spouses genuinely want to get better, but if all they hear is “this needs work,” then at some point too much negativity makes progress seem futile. Writers can take criticism. A serious writer doesn't need the typical 5:1 praise-to-criticism ratio that researchers say brings out our best effort at work or at home. But most writers also want to know that there’s enough promise in a draft to stick with the revisions. So, as a reviewer, you want to believe in the draft at least a little and not let the doubting take over entirely.

I’m an imperfect spouse, I will be the first to admit, and sometimes I agree with Faulkner’s Addie Bundren that “words dont ever fit even what they are trying to say at.” So I am grateful when I find a book like John Gottman’s The Seven Principles of Making Marriage Work, and I often read columns like Lisa Taddeo’s “My Husband and I Don’t Speak the Same Love Language” with sympathy. Since I suggested in a previous essay that the clash between humanities professors and their institutions might require either divorce or a really good couples therapist, I thought I might devote today’s newsletter to the same metaphor, only with the emphasis on believing. Namely, how might institutions or administrators strengthen their relationships with teachers? I use “teachers” and “faculty” interchangeably, but today I am also thinking of my K-12 colleagues.

We use the five love languages to talk about everything, so let me be clear. I am not interested in applying all five to faculty life, and my thought experiment is more figurative than literal. For instance, I do not believe that teachers who associate physical touch with intimacy in their private lives will necessarily respond the same way to a dean who creates a secret handshake with them or gives a fist bump while passing them on the quad. There are limits to every metaphor.

However, I believe that many teachers approach their work with mindsets that are fundamentally different from the philosophies that motivate principals, deans, presidents, or trustees. These are not merely agree-to-disagree differences: they are hardening into calls for faculty unionization. It’s possible that times of scarcity and the difficult decisions required during crises like the Covid-19 pandemic create irreparable divides between administrators and teachers, but tone and sincerity still matter. As a friend of mine once said in response to a major blowup between faculty and a college president, “this is soft tissue stuff.” Sometimes nothing matters more than the soft tissue. And so Gottman’s book might be better reading for many administrators than the latest in corporate leadership fare.

How to speak a teacher’s love language

1. Assume you are professional equals.

Teachers don’t think of themselves as subordinates to a boss. They think of themselves as experts in their craft. Many teachers have no aspirations to sit in the principal’s, dean’s, or president’s chair and would not regard those positions as promotions. Teachers see the classroom as the highest realization of their calling, and they need to know that what they do is as important to the institution as managing budgets. Understanding that and communicating it genuinely will go a long way toward building a culture of respect and mutual support. Gottman says that allowing your partner to influence you breaks down power differences in a marriage. Insert “teacher” for “partner” and “institution” for “marriage,” and the same principle applies.

One president at my former employer would visit every faculty member in their office on their birthday. He was a retired brigadier general, an effusive man with a double dose of Type A, and it was sometimes hard to get a word in edgewise. Mostly he wanted us to know that he was a big fan of our work. But he also asked pointed questions about college policy and curriculum in those visits and really listened to honest criticism. Later, in his public remarks, he would playfully refer to being beaten about the head and shoulders by faculty, but we knew that he was allowing us to influence him at the one-on-one level. 30 minutes per faculty member at that college meant about 50 hours a year in those birthday meetings. It was a worthwhile investment in goodwill. Faculty are more often summoned to the president’s turf — the conference room or administrative building — for serious conversations. Nothing conveys mutual respect like holding some of those tête-à-têtes in a teacher’s professional space.

2. Protect and preserve autonomy.

The teaching impulse requires freedom to invent, adapt, and tailor content to a particular group of students. Standardization is often the enemy of this impulse. Teachers know that accreditation is necessary, that some alignment of curriculum is necessary to avoid wildly different outcomes. But no teacher anywhere has ever rolled out of bed in the morning jazzed to hit an assessment benchmark.

Dan Pink’s Drive is more than a decade old now, but it offers as lucid an explanation of what motivates teachers as any resource I’ve seen.

The excitement of teaching springs from the sense of limitless possibilities, from the tingle of risk. Jane Elliott’s 1968 Blue Eyes Brown Eyes experiment was an impromptu response to the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr., and while Elliott’s method continues to provoke debate, I’d defend any teacher like her who wanted to try something new. Our brains did not evolve to learn in a straight line from a predictable plan. Sometimes we need the lightning bolt to the amygdala when the rocky path up ahead begins to slither and rattle its tail. In a moment like that we comprehend fully — with our whole body — that snakes are deadly.

Teachers experiment because they know that learning requires such novelty. In writing, the technique is called defamiliarization: rendering the familiar strange through unexpected details and thereby cementing those images in our memories. It’s why Steven Spielberg filmed Schindler’s List in black and white but broke with the pattern when he wanted us to follow a little girl in a red coat as she ran against the current of people being herded through the streets, fled to an upstairs room, and squeezed under a bed to hide. And later that same novelty destroys us when we see the little red coat being carted away with other bodies on a wheelbarrow. There is a maxim in Spielberg’s use of the red coat: a thousand deaths is a statistic, but one death is a tragedy. What we learn from that unexpected flash of color, we never forget.

Teachers are always looking for that twist of the kaleidoscope that changes how we see the world or that unlocks our grasp of a difficult concept. Nothing communicates respect more than defending their freedom to toss out the plan.

3. Take money off the table

The studies Pink cites in Drive show that monetary rewards actually get in the way of complex cognitive tasks, that people perform better when they’re paid enough that they don’t have to worry about it. But the inverse of this principle must also be true: teachers who are aware that they’re not paid enough or who constantly have to justify themselves in economic terms will assuredly perform more poorly because of that distraction. Even if you didn’t get into the profession for the money, at a certain age you begin to understand that salary is one way of expressing respect. Make baseline pay respectful, and many teachers will be grateful to think about anything else.

Taylor Mali captures the idea in his spoken word poem “What Teachers Make.” Teachers just define “make” differently.

One of the deadliest preoccupations in higher education now is ROI, or Return On Investment. When ROI trickles into academic assessment, or when faculty are asked to demonstrate why their particular major is worth the price of tuition, it’s just another way to erode teaching and learning with the money distraction. The reason why people are obsessed with ROI is understandable: it’s because college costs too much and therefore poses an enormous financial risk. Financial stress creates absurdities like this article from Southern New Hampshire University, which ostensibly lists the top seven reasons why college is important. A teacher would write that list in the exact reverse order. And maybe add something about knowledge, culture, critical thinking, citizenship, and creativity.

Teachers don’t set the tuition, and they can only control the quality of what they offer, which they measure in relational, not transactional, terms. It’s a simple formula. Throw money onto the table and drive curriculum with economic rationales, and watch teacher performance and wellbeing plummet. Take money off the table, place the emphasis elsewhere, and watch the quality of teaching and morale soar.

4. Sometimes let the teacher be the star

I am a competitive person, and I can understand why someone who has climbed the leadership ladder might want to be seen for that success. For other leaders it might be a sense of obligation that keeps them at the front of the room: a desire to show that they are working hard, pulling their weight. And we’ve all seen the autocrats who need the microphone for control. But just as my former president showed respect by visiting me in my own office, ceding the spotlight to a teacher can show that you really value them.

One of my favorite assignments for a first-year seminar was once modeled after the NPR series This I Believe. After listening to several radio stories from the archive, students wrote and recorded their own “This I Believe” essays. At the beginning of this unit I frequently invited colleagues to class to share their stories about a core belief. Over the years those guests included the Director of Facilities, the wrestling coach, and the coordinator of Community-Based Learning (also a Quaker minister who officiated my wedding). But it also meant a lot to me that whenever I asked the Dean of Faculty or the President to participate, they always accepted. Frequently I shared my own “This I Believe” story alongside theirs, and they stayed for the discussion that followed.

Many teachers might forego such an invitation out of respect for an administrator’s time. But if a dean, president, or principal offered themselves as a resource or even just asked if they might drop by the classroom sometime, they might be surprised by how that expression of interest and admiration would enrich their relationships with teachers.

I’m not sure where this started — if a plenary speaker mentioned it at a conference for deans or if it began more organically — but it has become fashionable for deans to begin faculty workshops by reading poetry aloud. I’m sure that some of these intros are more than gratuitous nods toward the arts and humanities, but they can feel particularly disingenuous if a literature department has just lost several tenure lines. If there are poets teaching at your college, you might consider asking a poet to perform one of their own poems for the occasion. Take your seat and invite the teacher in from the margins and bask for a few moments in their light.

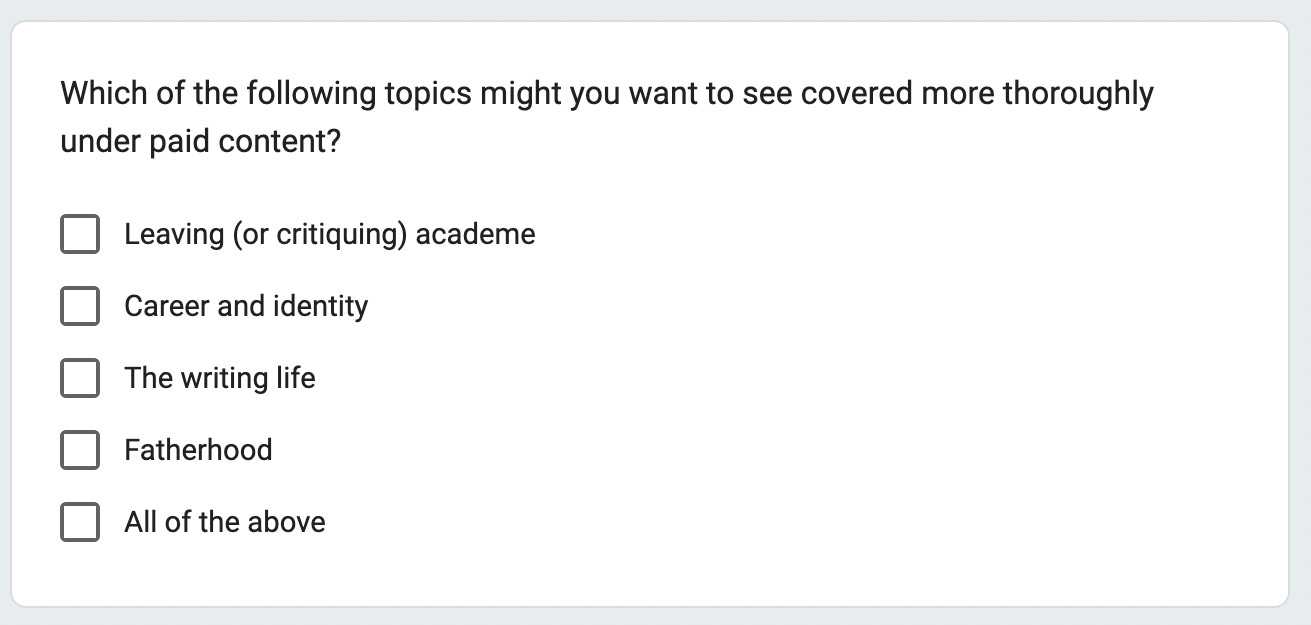

Thanks to your support, I am now approaching the point at which it might make sense to add paid content to The Recovering Academic. Over the next few months, as I plan the future of this series, I’d be grateful for your feedback on topics that you’d like to see covered more deeply or new features that you’d like to see added. If you’d like to make suggestions, please complete this Google Form. Or you can always send me a note at dolezaljosh@gmail.com.

Beat me about the head and ears!

One thing that bugged me was how difficult it was to get the "spirit shoppe" to carry our creative works and when they finally did, they shoved them in a crate on the floor. Not the most encouraging ethos.