I Could Feel the Beating Heart of My Mother

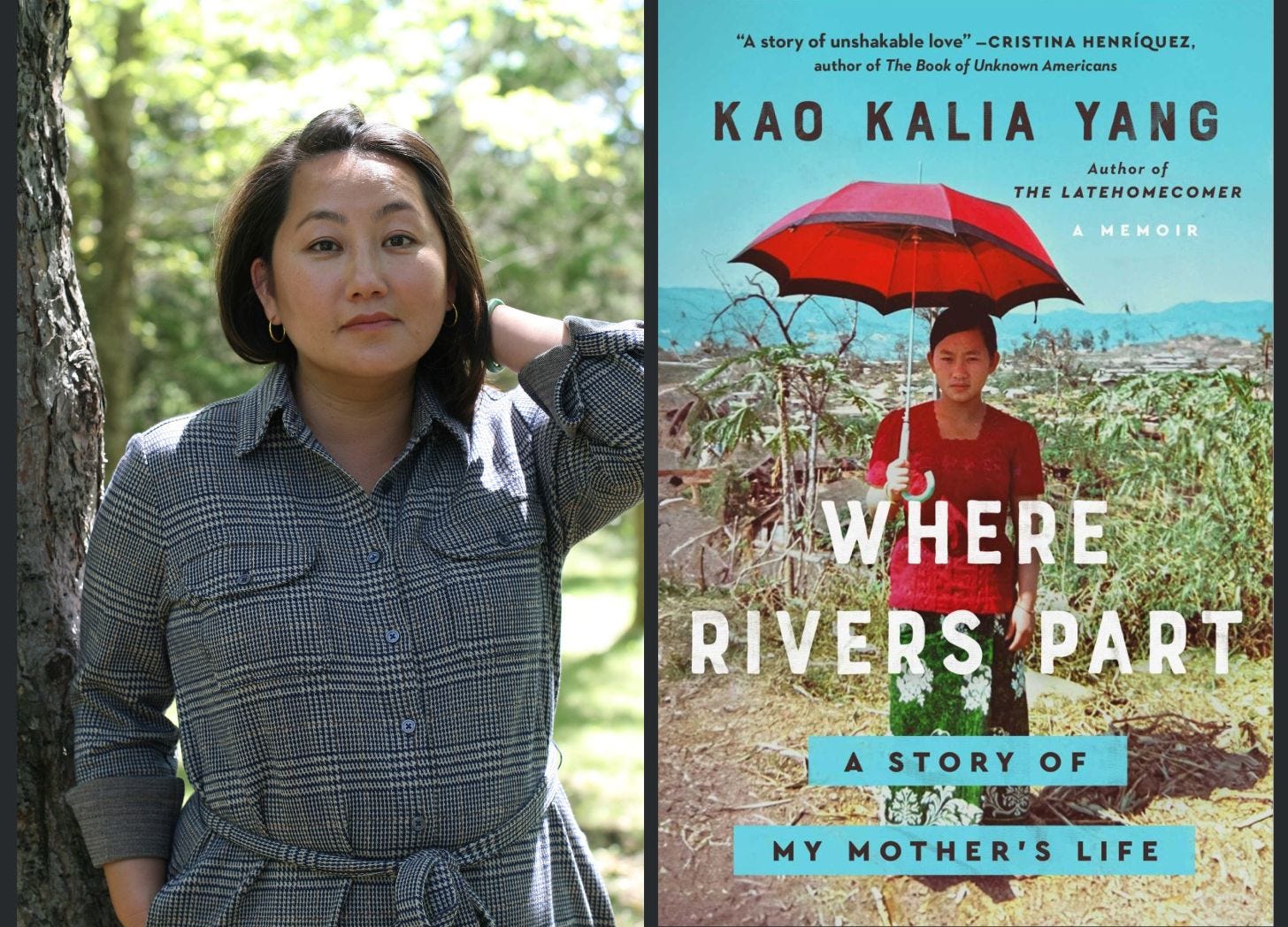

Kao Kalia Yang's forthcoming memoir, Where Rivers Part

Kao Kalia Yang is a Hmong American writer best known for her family memoirs, The Latehomecomer and The Song Poet, and for her children’s books, including my kids’ favorites: A Map Into the World and The Most Beautiful Thing. She has won multiple Minnesota Book Awards and many national honors, including Soros, McKnight, and Guggenheim fellowships.

I was honored to speak with Kalia about her forthcoming memoir, Where Rivers Part: A Story of My Mother’s Life, which you can pre-order at Bookshop and wherever books are sold. We considered the difficulty of writing about loved ones and revisited the most powerful scenes in the book, such as her mother’s attempted suicide in the Ban Vinai Refugee Camp in Thailand.

Today I’m sharing a free excerpt of our interview. Perhaps you’ll consider upgrading your subscription to read the rest of our conversation on Friday. In the second installment, I’ll go behind the scenes with Kalia to discuss two pivotal moments in her book: a scene in the camp hospital, where Kalia’s mother and father renew their commitment to one another, and the final scene, where Kalia’s mother travels back to Laos to visit her own mother’s grave for the first time.

There is no living American writer who I follow more closely than Kao Kalia Yang. You’ll feel her power in our interview, and I hope it prompts you to read her work for yourself.

A Conversation with Kao Kalia Yang

Joshua Doležal: Kalia, it's so good to see you. How many years has it been? Feels like seven years, maybe? Six?

Kao Kalia Yang: Ages. But it's good. I see you as a friend, so it's good to see a friend.

Joshua Doležal: Oh, likewise. It's nice to hear. Last time we spoke was for a podcast, and I feel like so much has happened since then. That was pre-COVID, that was pre-Guggenheim, probably more book awards than I can count, because you seem to win them at an alarming pace. But can you tell me what has changed in your life since then?

Kao Kalia Yang: So much. That was before my stint as the Edelstein-Keller Writer in Residence at the University of Minnesota. That was before the host of children's books. You know, I'm on my fifth children's title and in the coming year, there'll be three more. So I built a bit of a career in that world as well. Lots of changes, some good and some less good. Aging is never fun, Joshua.

Joshua Doležal: Tell me about it. I'm coming up on 50 in two years, so I'm thinking about that all the time. The Most Beautiful Thing is one of your children's books and that's a favorite in our house. It's a common request at bedtime, so I'll look forward to your new titles.

The book that we're talking about today, Where Rivers Part, is the story of your mother's life. And there are so many fascinating aspects to it, but I'd like to start with point of view and genre because both of those things are culturally specific concepts. And so far, I don't believe you've written anything that you would call fiction. Is that correct?

Kao Kalia Yang: I have fiction stories published for young adults. I have a book that's coming out, which will be my middle grade debut fiction. So, yeah, and when I was an emerging writer, I dabbled first in fiction as a kid, it was all about monsters in the closet. Intestines coming out…

Joshua Doležal: Very season appropriate! But you've really made a name for yourself as a memoirist. I don't know how you think about those categories, because I think in some cultural communities, they're more porous or fluid than in Western culture. So when you think about the difference between fiction and nonfiction, how do you distinguish?

Kao Kalia Yang: For me, you know, nonfiction has to do with facts. It has to do with the facts of a life. You have to get that right. You know, it's about accuracy. Fiction, anything goes. For my own body of work, Josh, we talked about the beginning. I knew that I wanted to start out in nonfiction because I knew that sometimes people are moving from the edges of their experiences toward the heart of it. I kind of went right for the heart of it. But I knew that the stories that I came from were nonfiction stories, and when the name Kao Kalia Yang emerged in the world of writing, I wanted to emerge from the truth of our stories.

There was that thing that I didn't want to take away from my family or my people, my community. And so I knew that I wanted to start out in nonfiction. I knew that I wanted to start out in adult. Because I wanted to establish that I could write, and then I could play. And I think we see that with the children's literature.

Right now, my next big adult project is fictional, adult fiction, and I can feel my heart expanding in so many ways. You know, I started from such a constricted place. And that expansion is humbling to witness, but it also feels like it was a gift that I didn't know I was waiting to give myself.

But yeah, for nonfiction, it's the facts of a life. There are real people, Josh, and there are real consequences if you get it wrong. There are real considerations, particularly for relationships, and I'm nothing if not a relational person.

Joshua Doležal: Well, everything that you write has that community or collective quality. And just one example in the epilogue – you thank your family for the time to write. So it seems that this isn't about personal branding for you. It's a representation that you see as an honor. And I don't know if you feel it as a duty. I was thinking in terms of genre that you're now giving a gift to yourself in fiction, and you've had some awareness of being a first in a Hmong-American literary tradition. Has that kept the focus on The Latehomecomer, on The Song Poet, and now on Where River’s Part — a series of nonfiction stories that build a foundation for the Hmong community? Has that been a kind of obligation you felt?

Kao Kalia Yang: That's a truth I've lived. It's an interesting question, but I do see this as, in many ways, the three books are a trilogy, this closes up that trilogy for me in a very real way. So there's like a sigh of relief. Now, there are all of these other stories that are knocking on my door and I'm going to open that door, open that window and see where it goes. I think I saw it as a responsibility, whether I knew it or not, whether it was conscious or not, it was something that I know I wanted to do and to do well.

Joshua Doležal: You do it so well. There's so many things I want to talk about in this lovely book. But before I lose the thread here, the point of view is tricky. So the reason I ask about fiction and nonfiction is you are writing the story of your mother's life in nonfiction — in the first person, meaning that the speaker of the book is your mother, not you. And so this might seem to a lot of readers like an impossibility.

I use the clumsy term “perhapsing” – sometimes nonfiction writers will put themselves on the ship, you know, from Ireland and they're trying to conjure an imaginative scene with their ancestor. But this is something quite different. It's more like a channeling or a vision.

How would you explain what you're trying to do?

Kao Kalia Yang: You know, this is something that I think I've been working a lot on personally across the body of my work. I wrote it in a variety of ways, trying to get as close to the story as possible. So third person, second person, and the first person voice, when I entered into it, I could feel the beating heart of my mother in so many ways. It's an incredible responsibility, as somebody who understands the importance of representation to take on.

But for me to enter so fully into her voice. That I could do the other work that was true to the story that she lived, true to the woman who loved me and that was, I mean, in many ways, this is the deepest I've ever dived into a life, and I don't think I could have done it in this way if it wasn't my mother. And yet, because it is my mother, I wanted to do it justice.

This is going to sound like a tangent, but it's the same thing. When I was in high school, I took an acting course, Josh, and all through the semester we were working toward these scenes. And so, on the final day of the presentation, I got on stage and I was supposed to inhabit this character and I knew that this character was really nervous and fearful and I had entered so fully into the character. And I hadn't realized it until the audience started saying, oh, my God, she's so scared. Get her off the stage. And the teacher said, get her off the stage. So he cut into the scene and took me off the stage.

And in the end, it was so uncomfortable because I was acting fully deeply, but the audience didn't get it. It was somehow impossible that you have this really quiet person who never talked that they could inhabit somebody else so fully.

It's exactly the same as what I've employed in my career from a craft perspective, right? You draw the scenes, your facts, and you enter fully into it. In terms of the experience of writing the book, every time I entered the pages, it was almost as if I was transported. A magical thing happened, you know?

But the scariest thing is when you show your mother, Josh. When you tell your mother what you're writing from her perspective. I was nervous. I sat down with my mom in our favorite place, which is the garage where we each have a fly swatter, and we're going at it, and I'm reading and I'm telling her explaining to her and she's just weeping, and I look at her face and I'm scared to believe it. But maybe I did do pieces of her story justice.

Somehow in the space of this book, the only way I felt I could be honest to my mother was to use the “I.” And of course, you and I know that this comes from what — we're mid-lifers now, so a life of feeling through and experiencing.

There were things I was waiting for. I knew I didn't want to write this book until I'd fallen in love. I knew I didn't want to write this book until I had children. I knew I didn't want to write this book until I saw my mother as a grandmother. And so I was like a horse, waiting, waiting, waiting, and finally the gate goes up and I run.

Did I run in the direction that I think I would run? Of course not. So in many ways, this is for me, my most feminist, my most intimate book.

Joshua Doležal: Well, I'm thinking of all kinds of scenes. The love story between your parents in the jungle, when both families are in flight and you reconstruct that beautifully, the class consciousness between them, that your mother comes from a wealthier family and becomes aware almost immediately that she's married, in her words, a poor man.

All those details are so nuanced and specific, and they demonstrate such a profound understanding of your parents, an empathic understanding, and there are also moments, and I don't know how these stories are passed on — if it's from individual to individual or in a more collective kind of space — but I wanted to ask you about the chapter called “Little Cucumber,” and I might be getting this wrong now, but I think Little Cucumber was your mother's sister. An older sister who died of illness.

And your mother's mother, your grandmother, had made this ornate jacket for her and couldn't bear to give it up. And kept it in a chest and then let your mother wear it one day when it was raining. And then she just disappeared. I'm sure I'm summarizing it clumsily.

So perhaps you can help me tell that story better, but there are supernatural elements to it because when your mother is found, she said that Little Cucumber is the one that drew her away and then the jacket was put away and never worn again. So there are these spiritual or supernatural layers to the story because it's so far removed. It's a memory that wasn't even your mother's. She was too young to even remember it. So it's a story that was told to her that she's told to you?

Kao Kalia Yang: I love this question, Josh. I first heard the story from my father. My father said, do you know that your mother's name was not true? You know, as a kid, and we'd be like, why?

And he'd tell us this ghost-like story. And so then I remember asking my mom and she kind of said, that's what people told me. So she tells us the story, but it wasn't until I met my uncle from Laos — the one who found her — and he said, she's saying Little Cucumber’s words and she came to life. And he talked about holding my mother close on that night and feeling her against his beating heart. And so you're exactly right. This isn't a one-off narrative, right? This is accumulation of all these stories told from different perspectives that I've collected and held on to, so that when I read that chapter to my mom, she was quiet for the longest time.

And she said, yes, so that name, I don't know what that name was. All I know is this name. That's how my mother responded. But that's how it came to me first — as a ghost story from my father, as an offhanded story of how it happened from my mother, and then all of these details came from my uncle-in-law.

Joshua Doležal: So your mother's name was changed as a kind of distraction so that she wouldn't be discovered again, or that the spirits wouldn't find her, right?

Kao Kalia Yang: Protection. To protect her identity and her life.

Joshua Doležal: And forgive me if this is an ignorant question, but did you change the spelling of your name in the book for that reason as well? Was that a similar protection?

Kao Kalia Yang: Oh, lovely questions. So I asked my mom, I said, how do you want me to write the names? And she says, please write them in Hmong. And so I wanted to honor that.

So I became Kablia in Hmong. You know, the most Hmong spelling just to honor her wish.

Joshua Doležal: There are some excruciating scenes as well from the Ban Vinai Camp in Thailand, where you were born, and the stress of that, the malnutrition, all these things that led your mother to have a series of miscarriages. And you told me the story before that she was so despondent that she wanted to just die and go be with the children that she'd lost.

And you, in this first person account, become her and take us into that suicidal ideation where she walks through the market in search of pills that were used to polish silverware, I believe, that she was going to take to poison herself. And I hope it's okay to ask this, but that's one of those examples — and I'm thinking of MFA workshops, where people will tell you some things aren't your story to tell, and so I don't know, were you asking permission to tell that story? Was this one of those things your mother wept about and how did she feel about you sharing that with the world?

Kao Kalia Yang: No, Joshua, I remember it because I was alive. So in that way, the story, when we talk about how the story gets to us or how we find the story, I lived through that with her as a child, knowing from my aunts and my uncles that my mother tried to kill herself. You know, for the longest time, she couldn't talk about it.

So it was a silence in our lives, but I knew it. And as a child, you think, oh, maybe there's only two of us on this side and there's more of them on the other side. The math just wasn't in our favor. You know I had a miscarriage as well and I would never have understood if I hadn't had that miscarriage myself, Josh, the feeling, the pain, the grief, the kind of emptiness that you live with.

So, after I had my own miscarriage, it was my mother who guided me through, who helped me make sense of this loss, or at least meet it. I think that's the appropriate word, meet the loss, because I would have run away if I could. I would have done anything, but my mother was there to guide me.

And somewhere along the way, I realized — she's gone through this so many times, and then the years make sense, the timeframe, everything. And I knew of the difficulties of my mom and dad's marriage. They couldn't hide it. Children see so much, and we feel so much. Even in a space where it seemed there was no room for our feelings.

The thing about my mother is that she has always raised me with her truth. She's such an honest person. And so I think in that honesty, she's taught me one thing: to be honest with my truth. There is no room to hide when you really love someone. You have to be able to see them.

It was an incredibly painful story to write, but I think also that both of us breathe, if that makes sense. And I think for my mother, it made sense of it for her as well. You know, I write these books and there's so much pressure because you want to do it right. Because you want to honor the people that you love so much.

I have to be honest with you. Part of this writing was in many ways, my attempt to help my mother make sense of her life, make sense of all of these things that have happened to her, that have happened because of her. And so in that way, I offered that as an offering into the quiet part of her heart, into the quietness of my own.

And then I think that is something that takes a long time for a writer to realize. That when you truly connect across genres, when you truly connect with someone, you know shamans — when they go on a spiritual journey, they're fighting for the soul of another. And you go not knowing if you can return, because you're traversing worlds. I do something like that sometimes in my writing.

Joshua Doležal: That’s so powerful.

Kao Kalia Yang: But the odds are so, like, you cannot do anything less. If you want to emerge in the end with the thing you love, the person you care about, you cannot do anything less. There's no room to hide. And if you give people room to hide, if you hide from yourself, the whole of the history then is altered. And where's the justice in that?

Joshua Doležal: That's so lovely. The idea of going in a shamanic way, across worlds on behalf of another and bringing shape and order and meaning to what have been frightening, confusing stories or experiences. What a gift for your mother and telling that story. So that is perhaps the most painful part of the book for me.

Another nuance in your parents’ relationship is this class consciousness. Your mother had to leave her family. And she felt the loss of her own mother keenly and had some doubts early on about whether she'd made the right decision to elope with your father in the jungle and join his family.

And this is a kind of nuance that I think is not understood well by people outside of a refugee community, for instance, because there's a kind of equation of everyone. Or a feeling that there's an equalizing effect of being in that experience or in a camp.

And so I was struck that in the jungle, that the families fleeing soldiers would still retain these very specific identities. You know, flight and survival weren't just the same for everyone. But I was even more surprised, and I think this is maybe a softer, more humorous part of the narrative — that [class consciousness] survives in America, your father hates to go inside [stores] because he can't bear to see all the things that he can't buy. So he waits in the car. And your mother loves to go shopping, even if she doesn't have a lot of money, because she likes to see what's available.

And so these are what we call scarcity and abundance mindsets, right? And you have a whole chapter on the Mall of America, which your father also hates. I don't know if you meant it to soften some of the other elements, and I don't even know if I would describe it as comic. But it's humanizing. It's such an important layer of the story. I don't know if you want to say anything more about it.

Kao Kalia Yang: I do. The depiction of marriage in Where Rivers Part – I mean, marriage is not a happy place, you know, neither of them are evil, but these things happen. These things that are happening around them and to them, and they're so young. They're my parents, so I've always seen them as the adults in my life, but as a 40 something year old writer, now writing the story of her mother and father's love story, you know, from her mother's perspective, I can see how young they were at every point. The arguments were so heated up, you know, and in the moments where she stays, like that moment in the hospital where she stays, there's really no promise made. It's just a choice you’ve made. It's a choice you're making and you stay and you can tell your daughter all these years later that I don't know why I stayed, but this is what happened.

I think the depiction of marriage in this book, it's more complicated than I thought it would be. But speaking as somebody in a marriage, I know that there are years or decades where that's just how it is, and the fact that with all of these differences, she knows his weaknesses better than anyone else. My father does not speak about my mother's weaknesses, but he knows them. They were so young when they came together. And with all of these forces coming at them, and you can feel the forces on their marriage. Somehow they are still here as these sheltering figures in my life. That is incredible.

And when I think about it from the perspective of a 42 year old writer in a 12 year marriage, I'm like, I would have left him. I would have left him, you know, but this is where nonfiction is nonfiction, Josh — she didn't. And then this is where you want to be very honest to the marriage.

And so the depiction of marriage in Where Rivers Part, I think it will be a topic of conversation when the book comes out, particularly from a feminist perspective.

Joshua Doležal: I have a kind of larger question about how your writing fits into Asian American literature. And I don't know that this is unique to Asian American literature, but I recently spoke with Carol Roh Spaulding, whose debut short fiction collection won the Flannery O'Connor Short Fiction Award at the University of Georgia Press. And she grew up, in her words, white, but her mother was Korean. And so she had this kind of double consciousness of herself. But she described a Korean trope, Han, which is this elegiac mode – there's a lyricism wound up with elegy and a kind of yearning, a deep sadness in Korean literature.

And I hear a very similar echo of that in your writing. And one, I don't know if you see that as part of how Hmong literature fits within the broader category of Asian American literature. And two, I wonder if you see that as a kind of universal feature of writing by any oppressed people? I hear echoes of that in Czech writing. Also a people with centuries of foreign occupation and oppression. That's kind of a complicated question.

Kao Kalia Yang: I love it because I think it situates the book in time. I'm writing about people who are refugees. People who know war. People who know hunger. Who know desperation. Who live in impoverished lives.

You know, for my mom and my dad and the generation that raised me, it wasn't, none of them would say, “I had a happy life. I had a beautiful life, sweetie.” No, none of them would say this. We are here despite of all of these things. We're here because of all of these things. So here we are, and where do we go next? That was always the question. So if you begin from that place where you are lucky. The children are lucky. The adults, those who've lived through the war are not so lucky at all.

This is the story of their life. There's this hopeless element to it. The same is true when I write about my family, when I'm in the realm of memoir, Josh. I want to make it better. I want to be there, but I can't make it better. That's where the nonfiction is. It's been so heavy. This is the life and this is the love and that there is where the beauty is and that there is where the triumph is, that there is a thing that keeps my own heart beating true.

Yes, it's Asian American. Yes, I'm writing in the vein of so many of the great Asian American writers who I respect, Kingston, Tan, you know the influences, Baldwin, Morrison, Angelou, Little House on the Prairie, because Kao Kalia Yang grew up in Minnesota, you know, all of these things are coming into play.

Joshua Doležal: As you're talking, I'm thinking of the World War II series that I've seen, Band of Brothers, and then The Pacific. So often it seems like even with this long history of Asian American writers, the Asian experience is still Other and so in The Pacific, it's just so painfully Other, because the slur “Japs” is used constantly. And you're just embedded in the American soldiers’ mindset.

And so I see your book as balancing that. I don't know how to ask this exactly, but do you see this as an American book or is it more a Hmong book?

Kao Kalia Yang: I am an American, a Hmong American writer. These are the facts of the life. These are the facts and the circumstances that have governed the development of the story and where it is now in the landscape of the world. But it is a book that crosses, I think, nation states. Oceans of time and space, and that way the book is, and this is an ambitious statement, but it's a universal book that can live across times.

I knew that in that way, it almost felt to me in the writing that I was tapping, not only into a balancing perspective, but into a truth that will survive me, my mom, of course, but me. And perhaps my children. We live in a world that is creating refugees every single day, Josh. In how many stories’ origins, how many people will write about these wars that we see on our television sets in the next ten years?

I don't see the end of warfare for humanity. As much as I'm a pacifist, as much as I believe in the beauty of peace, and for all of those lonely writers who are coming along, who feel they might be the only ones. If they should stumble upon Where Rivers Part, I hope that it is a friend to them. It is written in the English language. There's no translation interest as of right now. And I think all of these things govern access, govern who gets to read this book. For the Hmong American student in college, who might meet this book in a syllabus, I hope that it is a welcome sight, a necessary hopeful sight. But for all of these other refugees, I hope that they find in it threads of their own story, threads of their own survival.

But yeah, Kao Kalia Yang is a Hmong American writer, working from 2023. These are the facts.

Joshua Doležal: I hope it’s okay to ask — in the camp, you chronicle your mother’s suffering so vividly, but you don't zoom into each one of her miscarriages specifically. But you do zoom into one pregnancy later, before your brother was born. Why?

Kao Kalia Yang: You know, that's how the truth of it felt. I think the American miscarriage took such a prominence in her mind, in her heart, and that's my own. Everything before was unpreventable, but this one could have been. So it haunts her in real ways. She sometimes talks about how if all of those boys had lived, Dawb and I would be surrounded by brothers.

And when we were young, when we were bullied, there were a few moments that we thought, would we be stronger with like six brothers? But the reality was, there was her and there was me, and there was the ghost of the brothers, and then there were all of the young ones. And I think my mother always felt in that way she had to raise us strong. She herself had to become much stronger than I think she ever wanted to be. But that was her life. And that was her truth, the most important thing I've learned from my mother as her daughter. And that's the author of Where Rivers Part: to live your truth without excuses, to live your truth as gracefully as you can, and to let that stand as a testament to the human experience.