Literature is a cord that draws us together

The thread between Chaim Potok, Willa Cather, and me

The spring when I knew that I would leave my job as a tenured college professor, I began having dreams about childhood. Some came during sleep, and some were daytime reveries, but they all took me down the stairs of my family home into the basement, a warren of two-by-four framing and cement where I slept. My mother tie-dyed some sheets and tacked them over the studs to give me a little privacy. My doorway was another sheet with a sleeve that slid along a pull-up bar that my father had screwed into the jamb.

I was afraid of that basement because I had to walk down into the darkness at bedtime, and every night I relived a scene from a Hitchcock film, where a woman breaks her neck at the foot of a staircase. I’d seen it by accident while playing at a friend’s house. He sent me to the kitchen for snacks, and I walked through the living room where his parents were watching the film, and I saw the woman fall. The image of her crumpled body – filmed from above, the vantage from which I looked down into my own basement – was forever burned into my memory.

Even when I’d switched off the light at the foot of the stairs and lunged across the gap to my room, bursting through the sheet in the doorway, I could feel the rest of the house stretching out beyond my flimsy walls. It was hard to read at night, because I felt exposed, the way a soldier who has seen combat does if he silhouettes himself against a window.

But after sunrise that room was my sanctuary. I read Tolkein there and Madeleine L’Engle and nearly everything by C.S. Lewis. By the time I reached high school, my mother loaned me her copies of Chaim Potok’s The Chosen and The Promise. Potok explores a fascinating relationship between two young men, Reuven Malter and Danny Saunders, who begin as rivals in a softball game and become fast friends after Danny smashes Reuven’s glasses with a line drive. Reuven is orthodox, studying to become a rabbi. Danny is a prodigy who memorizes huge portions of the Talmud but finds himself drawn to secular psychology and even sneaks to the public library to read Freud. Reuven and Danny represent Potok’s Romantic vision – more timely than ever – of trying to bridge two seemingly irreconcilable worldviews.

As a child I felt complete freedom to identify with Reuven and Danny despite the chasm between their backgrounds and my own. Publicly I was Reuven, the orthodox boy, conforming to everything my parents asked of me. But I became Danny in my bedroom refuge, where books opened up other worlds. I could not follow Bilbo and Frodo through Middle Earth or listen in on conversations between Reuven and Danny in Brooklyn without developing the conviction that the wide world also belonged to me.

My father might have had a premonition that reading was giving me ideas, or maybe he just thought I was being slothful, but he often barged into my room and told me to put the book down and come make myself useful. So I’d go pull weeds along the cauliflower row or haul the raspberry canes that he’d pruned to the burn pile. If I began by reading books for pleasure, my father’s disapproval spurred me on in the only rebellion I can recall from those years. In fact, I came to think of literature as a forbidden fruit that I could only enjoy in secret, the way Danny gobbled up books about science in the library.

I found all manner of hiding places, sometimes lying on the cement floor between my bed and a chest freezer that was kept in my room. When my father discovered that ruse, I sometimes sought the cave-like atmosphere of the wood room, a corner of the basement where we split larch for our stove. The wood room had two doors. One led to the stove, and the other opened into the garage. Sometimes I’d sit on the chopping block and read by the light of a naked bulb, listening for the creak of my father’s footsteps on the basement stairs or the sound of him rustling about in the garage. If I heard him approaching from one direction, I’d slip out the opposite way.

Our property ran along the edge of federal land, the Kootenai National Forest, and so I could always disappear into the trees. But I found it difficult to read in the woods. It was not just the ants and mosquitos that would jostle me out of the story, it was also the giant Ponderosas and White Pines, the sigh of wind high in the tree canopy. I had never heard of Thomas Paine then, but I felt something that he expressed perfectly: “Search not the book called the Scripture, which any human hand might make, but the Scripture called the Creation.” The forest was its own book. To this day, I struggle to read in open spaces. I prefer the womblike borders of a tent or to retire somewhere upstairs, the way a cloistress removes to her cell to pray.

I don’t know if I was destined to spend my life among books or if my father’s attempts to wean me of bookishness only deepened the allure. Maybe I would have been better off going to law school and reading for entertainment, the way more sensible people do. But the haunting of memory told a different story as I prepared to leave academe. To have transformed a forbidden pleasure into my livelihood and then to voluntarily walk away felt like toppling my king in a game of chess that I’d already won. But it was not a mistake to have become a professor. The closer I got to my resignation day, the more I wanted to cling to the passion that first struck me that hard and that true.

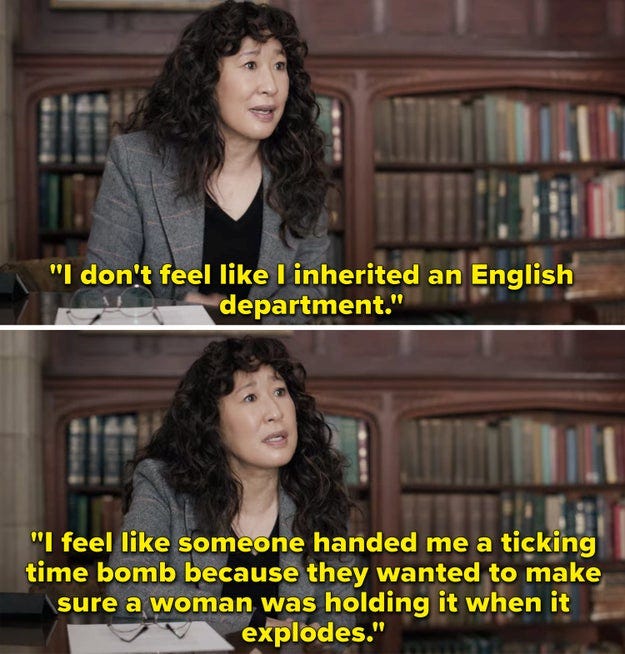

I wonder why my bookish childhood seems so rich with narrative ore when the profession that nurtured those early passions seems so thin by comparison. A few years ago I wrote a short story about a professor who organizes a feeble protest when an oil baron is invited to speak on campus. My story was influenced, in part, by Richard Russo’s Straight Man and Julia Schumacher’s The Shakespeare Requirement, both book-length satires of academe. Russo’s and Schumacher’s academics are overgrown children with eggshell egos and virtually no impulse control. At the time I wrote my story, I felt a sense of futility in faculty life that was later echoed in the Netflix series The Chair.

I watched The Chair as devotedly as every other English professor I know, laughing at what the series gets right and groaning at what it gets woefully wrong (I mean, Bill Dobson, WTF?). But I now see that framing academe with absurdity only plays into the hands of those who would bury the arts and humanities. The elitist tendencies of modernism and the self-negating effects of postmodernism have made literature uniquely vulnerable to ridicule within the corporate university. I have come to feel that this is less the moment for parody and deconstruction – no matter how germane those modes might be – than it is for reclaiming a Romantic view of the liberal arts. Sometimes the only thing a bully understands is a stiff counterpunch, which is the last thing you’ll get from a nihilist sneering between pulls on a cigarette. Less of Elliot’s hollow men. More of Fuller: “Always the soul says to us all, Cherish your best hopes as a faith, and abide by them in action. Such shall be the effectual fervent means to their fulfilment.” More of Hurston:

“When God had made The Man, he made him out of stuff that sung all the time and glittered all over. Some angels got jealous and chopped him into millions of pieces, but still he glittered and hummed. So they beat him down to nothing but sparks but each little spark had a shine and a song. So they covered each one over with mud. And the lonesomeness in the sparks make them hunt for one another.”

Hollywood captures the agony and ecstasy of medical research in Something the Lord Made, showing how the puzzle consumes the scientist, how botched experiments lead to a revelation that turns death back into life. And there are lovely films about writers and artists (Frida and Wonder Boys among my sentimental favorites). But we do not have, as yet, a film that captures the idealism that drives projects like Melissa Homestead’s The Only Wonderful Things: The Creative Partnership of Edith Lewis and Willa Cather or Harold Bloom’s The Anatomy of Influence: Literature as a Way of Life. Is this because literary scholars hide their big hearts behind impenetrable prose, so no one ever learns the real magic of unlocking a puzzle in a library archive? Is it because America has always been deeply distrustful of intellectuals, and intellectuals have responded by retreating further within their fortresses of pretension?

You might think that a recovering academic ought to be over all that, speeding down the highway with his top down and all his pages of research littering the road behind him. So, okay, there is a little of that. But six months down that road, I find myself returning to idealism as a birthright. Instead of leaving memories of the classroom or archive behind, I am drawn just as strongly to them as to those childhood scenes when books first called to me.

My graduate school mentor, Susan Rosowski, taught a seminar on Willa Cather that began on campus and ended in Red Cloud, the Nebraska home that Cather described as “the happiness and the curse” of her life. Like Sue, I took several groups of English majors back to Nebraska to experience the places that Cather immortalized in her art. The magic of the experience, for me, lay less in Cather’s talent than it did in her recognition that every place has its own genius, and it is the work of the artist to bring this secret into the light. In fact, Sue taught me that this is also the work of the scholar: to help others feel the richness of great art. It’s a Romantic idea, that we’re all in it together, that art and scholarship exist to deepen our intimacy with each other.

Cather understood that Nebraska was just as story-worthy as ancient Greece and Rome. In One of Ours, Nebraska is a place where a young man who feels trapped on the farm bathes in a horse tank on a hot summer night, gazing at the moon and thinking of Egypt and Babylon, how the same moon must have crept through prison windows, where captives like him lay forgotten. The narrator of My Ántonia, who leaves his rural hometown for the university, can only understand Virgil through the Swedish and Norwegian girls he knew in the country. “If there were no girls like them in the world,” he reflects, “there would be no poetry.” In O Pioneers!, a Swedish man and a Czech woman reenact the tragic story of Pyramus and Thisbe from Ovid’s Metamorphoses.

If you walked through the streets of Red Cloud, you could be forgiven for thinking it unremarkable. It’s the kind of place young people yearn to leave, the rural scene that Alexander Payne imagines as a wasteland. But the National Willa Cather Center and the many historical sites throughout the town and countryside now provide an economic engine for the community. None of this would have happened if Cather had not studied the classics, felt them deeply, and then brought her life experience – the places and people she knew – into conversation with that literary tradition. Red Cloud would be just another town that Progress forgot if it had not been for the professors, volunteers, and townspeople who worked side by side to transform the place into a living classroom.

I used to tell my students that literature allows us to see any place as belonging to the great human story. But perceiving our home places with such respect requires knowing something about history. It requires imagination. And it requires a Romantic belief in language as the cord that pulls us back together from all that has broken us apart.

When I hid from my father to read Potok’s novels, I was not trying to escape rural Montana. I was trying to understand my own life through Potok’s Brooklyn, through the struggle between Reuven’s loyalty and Danny’s independence within my own soul. I hope the day will come when the university remembers that one of its primary reasons for existing at all is the solitary individual – alone in his basement bedroom or her library carrel – striving to transform life into art or performing the reverse miracle of translating art back into a private or public truth.

Your phrase, "every place has its own genius, and it is the work of the artist to bring this secret into the light," inspires me. Thank you.

I was an English Major at a snobby college. Now that I look back, it really gave me very little. Perhaps four years in a beautiful nature environment. A bit of finding myself and my talent for writing. No real way to make a living! Not even a teaching degree (the snobs)!

The best thing about it was spending my junior year in Israel and discovering my Jewish heritage. Now I am a fully observant Jew, a grandmother of a whole slew of observant Jewish children and grandchildren. (I also read Chaim Potok s a child and never realized that I , too, was a member of that tribe, with all of its glorious customs and its way of life).

I hope you didn’t give up that part of yourself. It’s the best part of yourself. The Torah Jew.