Don’t miss the latest at Inner Life, where

shares an excerpt of his forthcoming book “Our Worst Strength: American Individualism and Its Hidden Discontents.”A Conversation with Leslie Wang

Joshua Doležal: I’m Joshua Doležal and this is The Recovering Academic. My guest today is Dr. Leslie Wang.

Leslie Wang: I mean, for me, honestly, like my tagline underneath the tagline of “I'll help you write a book” is, “I’m going to help you feel better about your life.” That's what it is. I'm going to help you suffer less in this career.

Joshua Doležal: Leslie grew up in Palo Verdes, California. She followed the coast south to UC San Diego for her bachelor’s degree and then many hours north to Berkeley for a Ph.D. in Sociology. Leslie’s undergraduate honors thesis on the adoption of Chinese children by American parents began as a way of understanding her own roots. The response to her research was so positive that her next step felt almost inevitable.

But then the reality of graduate school hit, and her personal passion turned into a grind of constantly trying to prove herself. After a postdoc at the University of British Columbia and brief stint at Grand Valley State University in Michigan, Leslie landed what looked like a dream job: a tenure-track position at UMass in Boston. But what looks idyllic on the outside doesn’t always feel that way in the trenches.

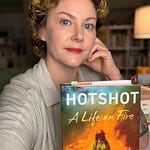

The turning point for Leslie came the very year she earned tenure, when she also completed certification as a life coach. After several years of experimentation and reflection, she finally made the leap into full-time entrepreneurship. Leslie is now the Founder and Principal at Your Words Unleashed, where she coaches clients on academic writing. But her services go beyond the nuts and bolts of wrangling research into a published book. And no matter your background, I think you’ll identify with her larger mission, which is to make work work better for us.

Joshua Doležal: Leslie, let's kind of go back to the beginning. I don't know if I'm reading this correctly. It's always dangerous to assume too much from the bare minimum you see on a LinkedIn profile, but it seems like you grew up in California. Is that correct?

Leslie Wang: I did. Yes. I grew up in Southern California by the beach.

Joshua Doležal: Were you in San Diego or…what was your hometown?

Leslie Wang: So I grew up in a city called Palos Verdes. It's like South Bay. It's basically part of LA County.

Joshua Doležal: Did you feel like your family was part of the region, part of the place?

Leslie Wang: Yeah, I think so. I mean, everyone I know kind of has a period of time where they reject to where they grew up. A lot of times I think that happens around high school. So, I grew up in a very affluent area that had a fairly high percentage of Asian people. It's even higher now, but it was maybe 20 percent when I was growing up. But I would say that it's still operated according to a very kind of mainstream upper middle class white set of norms. And so in terms of who you wanted to be, like who was popular, all those things. And so I never felt like I really fit in there. So I think that there were some seeds planted for me around racial and ethnic inequalities, class inequalities. I grew up in a really sheltered kind of environment up on a hill, separated from Los Angeles, and how that kind of impacts people. So once I went off to college, I really sort of rejected this whole idea of trying to really set yourself apart from society. And a lot of these sort of hyper competitive social status sort of things that can happen in areas that are more affluent.

Joshua Doležal: Tell me if I'm wrong about this, but I grew up in a blue collar family in Montana and a rural Montana town of less than a thousand people. And maybe 20 percent of that population lived actually in town. Everyone else was scattered through the hills above town.

And I grew up with a sense of deep connection to neighbors, to a kind of civic life – hunting culture, the idea that you would share tools or, you know, somebody needed to preserve food, then equipment gets kind of passed around between families, and all of that. And so for me, going into higher ed was a real shift because I was now part of a culture that was much more about I guess, even then, more about personal branding or sort of maximizing professional potential.

And so the idea of a place or belonging to a community was not really the priority, you sort of would dip in and dip out of that as you needed to, but the real focus was on, I guess, the Army slogan: Be all you can be. And so that was a real adjustment for me, and I think, as you were alluding to, higher ed forces us to make some of these sacrifices or choices.

And so that's a roundabout way of saying my perception of affluent communities is that there is less of a premium on togetherness and on community, and there's much more of a premium on what you described as hyper competitiveness. So you're sort of against the neighbor as far as competitors to get into Harvard, Yale, or something. And you don't really expect to end up back where you started, you expect to go somewhere else.

Leslie Wang: A lot of my peers have like their dream was to move back to where we grew up, because they want to raise their kids in the same way that they were raised. So no, I think you're right, though, in terms of like belonging. I'm not sure that I felt belonging to the local community, certainly not like in a neighborly way.

Houses were really far apart. And we weren't part of a church or anything like that. But I would say I have a very strong identity as a Californian, as someone from California, who really identifies with I guess, region, as opposed to like neighborhood. Of course, I have my friends, but not so much like community that I grew up with.

But it was always, and still is, the goal to move back there, to move back to California.

Joshua Doležal: Okay. So you still identify as Californian. You're not a Bostonian. Never will be.

Leslie Wang: I don't think so. It's been very good to me out here. I've been here for 10 years now and I wouldn't be the person I am with the family that I have and the job that I have without it. So I have deep gratitude. And then there's also the reality of like trying to raise kids when you don't have any family support and your lifelong connections with people are across the country. Or international too. So that's part of the connection to region too. I think most people have the option usually to live closer to their families. And that's one of the things that's really unique to academia and the military and maybe clergy is you just don't have that choice if you're really going to do it a hundred percent.

So I did it and now eventually move back.

Joshua Doležal: I'm just curious what defines being Californian to you when you think of that as a regional identity, something that gives you a sense of belonging, what does that mean?

Leslie Wang: I think it's actually about environment, like being close to the beach, being close to the Pacific Ocean. It's like topography. It's like sort of what constitutes nature for you, I think, is different depending on where you grew up. So I don't identify as much with like mountains and forests, but like the beach is really a place where I feel like I'm connected to something much bigger than myself.

And I associate that more with the Pacific Ocean than other oceans. And I just think the lifestyle is preferable, it's warm. I've experienced a lot of other things. And now I want to go back to what I knew.

Joshua Doležal: Yeah. I’ve found as I get older, those native places pull more strongly on me for sure. Well, let's talk then about your decision to go into academe. So in these competitive environments, there are all kinds of professional futures available to you. You could have gone into tech, right? I mean, that's a big part of California culture. You could have done anything. Why did you go into sociology and engineering? And go beyond an undergraduate degree to go on for a PhD?

Leslie Wang: So interesting reflecting on this now. I'm 46 and I made that decision when I was 19. But thinking back on it. I think I started as a Psych major, not knowing what that was, and then took some Psych classes, realized that wasn't for me. And I took my first Sociology class. It was just a big 101 survey class when I was a sophomore, and it was the very first time I felt like things that I had thought before were actually appearing before me in lectures.

I thought I had created the idea of, like, a self-fulfilling prophecy, or like, I don't know. I had all these ideas, and I didn't know if other people thought the same things. And then I realized there's a whole discipline that thought in a very similar way. And after that, I was like, okay, something's clicking for me here.

And I just became really sort of hungry to learn more about different aspects of using a sociological lens to understand gender and family and I became really interested in my ancestral roots during that time as a lot of college kids do. I studied abroad in China, and so I brought that into the things I was fascinated by as well, trying to understand things in a more global fashion.

And so the reason I ultimately went down the path of research is that I did like an undergraduate honors thesis. And it was on the adoption of Chinese children by American parents, which at that time, it was around, I guess, late 90s was sort of hitting a peak and I hadn't seen much research on it. So I just embarked on interviewing adoptive parents and trying to learn about both sides of it, the Chinese side, the American side, and I was like, oh, this is a way for me to kind of understand my own roots as a Chinese American person. And then I remember at the end of this summer sort of research scholarship thing that I had gotten, I think it was like a McNair Fellowship – kind of sets students of color and first generation students up for grad school success if they want to pursue it.

And so we had to give a research talk at the end. And I remember I gave a talk maybe 15 or 20 minutes on what I've been studying about Chinese adoptions. And someone came up to me later and said, That was my favorite talk of the day. That was the only one where I really felt like I learned something.

I learned something new. And I think this was maybe a faculty member and it just hit me, Oh, I'm really good at this. And I really enjoy it. And I'm someone that only does things, is really only motivated to do things, if I’m intrigued by it. Otherwise I'm not going to do it.

And so it was like, okay, let's see. And then many people, I think one of my instructors, one of my professors really encouraged me. One or two of them actually were like, are you going to go to grad school? I think you should pursue a PhD. I think you'd be really good at this. And so I did, but you know, I spent two years in Japan teaching English on the JET program and then I started grad school because I didn't want to go directly.

I wanted to have some amount of life experience before I started.

Joshua Doležal: You find that you're good at something and you get encouraged by your mentors and you follow that path. And there's a whole lot of, I guess, what you're committing to that is not apparent to you at the time. And so I guess going back to that decision, would you tell your younger self anything different from what your mentors were telling you then?

Leslie Wang: I think that's so hard. My mentors didn't tell me much about anything. They were mostly just encouraging what they saw as like a promising young mind without any indication of what that path looks like. And I never asked them what the life was like, because all I ever thought about was grad school is grad school. I didn't think much beyond it. Honestly, I didn't think about becoming a professor. I thought that would happen at the end of this long process. And so I didn't have to worry about it yet. And I was like 22, 23. So it's interesting. I had this inflection point a year or two into grad school where I almost quit my program because I felt like why am I killing myself writing these papers, doing all this work, feeling so much imposter syndrome, so much stress and anxiety in such a hyper competitive space when like only one person reading my work is the instructor of my class.

I'm like, I don't see the purpose of this. It's not applied. And I want to do something that's applied, that actually makes some sort of difference in someone's life, and what I'm doing right now is not doing that. And so I was investigating other options. I talked to my mentor and he was like before you do that, why don't you talk to another professor of mine who's really good at helping students.

And so she was like, you haven't taught yet. Teaching is the applied part of sociology. Wait. And so I did, I waited and I started teaching and it never got that much easier to be honest, but at a certain point I just sort of dug my heels in and was like now I'm in it. So I don't know, I feel like I did really question the path, I questioned the life but I didn't know enough about it and I think that's one of the things that professors probably could do a much better job of sharing with their students is that it's not easy, that there's so much hidden labor. That, in the grand scheme of things, you're really not compensated that well for what you're giving and that there are many sacrifices involved unless you happen to sort of hit a jackpot, which very few people do.

But, of course, I was coming out of the University of California system. They were all superstars, like it had all worked out for them. So I think for them it was like, well, it's all worth it. So I don't know that they would have said anything different to me.

Joshua Doležal: There's a kind of confirmation bias there. Well, I asked this partly because I've been sort of puzzled by how little has changed in the credentialing process. There's this huge exodus from academe by people like me and like you who were successful, who beat the odds, got the job, earned tenure, and even with all of that left. None of those stories are being told, I don't think, to prospective graduate students. And I know in my own case as a professor and as a mentor, I felt some shame in admitting to my advisees some of those conflicts I was having with my work. I don't know that I'd fully accepted that I wouldn't be in it for the rest of my life.

So I would sometimes caution them about the job market Yeah, you could go on and get a PhD. I'm sure you could get into a good program, but just be aware, if you can say no, or if you can take no for an answer, then you should do something else. Like you have to be the stubborn kind of person who's really going to just grind it out and not care about the odds if you're going to make it.

But that was only part of the story. Because, as you said, the life, even if you do make it, even if you do win at that game, the value proposition is steadily eroding, and I don't know how to have that conversation with students who are contemplating this, but maybe later we can circle back around to it, because you and I both serve people who are still part of the system. Like we have separated ourselves from it to some extent, but I coach graduate school applicants. I help people with personal statements, and you are coaching faculty with their actual research, and so we're still connected in a way but I just feel like the credentialing process has not really adapted much to the reality that there's this hemorrhaging of talent happening. And a lot of it has to do with the life. It has to do with the eroding sense of purpose. And I guess the overall value proposition of being a professional academic.

Leslie Wang: And the material scarcity of positions that pay you enough to survive on. And where I was UMass Boston, we had an MA and a PhD program. And the PhD program started the year that I started, and it was always intended to be an applied program.

So the idea was to give students research skills that they could then apply in research based positions. So they could have a current job and then be promoted in that job. For example, what we found was like a third to a half of students still wanted to become professors. So it was almost like, even though we weren't a ranked program in any way, the purpose was intended to be different, we still garnered students that were like, I'm going to be the exception. And I'm like, but this is not Harvard, right? This is not Berkeley. This is not Stanford. There's no guarantee of anything tenure-track wise at the end of this.

A few of them beat the odds and did get tenure-track positions. And then when I spoke to them later, they were like, I'm teaching a four-four, I'm living in a high cost of living area. We don't know anybody here. I have no time to spend with my kids. And I think were basically looking for an exit.

I think I'm similar to a lot of students in the sense of I had to figure it out for myself. And I think, even if I had known all the statistics and how terrible things were, and how this enrollment dip is coming and how many Sociology departments are being eliminated and will be in the next 5 to 10 years, I probably still would have been like, I could do it, or I want to see if I can do it.

And I think that's part of it, was this inner desire to be like, can I do it? I want to prove myself. And I think that's a big part of what drives academics, right? It's, it's a constant proving of yourself, but it kind of never ends. So you know, I think for me and perhaps for you, I reached a point in my career where I felt like I had proven myself enough and I still wasn't happy. So it was sort of like, Oh, okay. If I'm looking for external achievements to bring me a sense of inner satisfaction and self-worth, that's actually not working. So then I had to look for a different way.

Joshua Doležal: I like how you framed that: availability of information is no guarantee. Even if you know all of the information, you might not choose differently. And I know for myself, all of this looked just so different from the vantage of a 25 year old with no other responsibilities or commitments. And later, you know, as a father, and thinking about money in a different way than I would have as a single person in my twenties. That's the kind of thing where the value proposition doesn't age well always as you move through your life. And you can't be too hard on your younger self. You have to be compassionate with the decisions that you made, given the information available to you at the time. I just, I don't know if there's a better way of telling that story.

The way that I try to do it with my clients who are applying to medical residency or applying to PhD programs in the sciences or in the humanities is to really focus on fit, to ask them to go through a rigorous process of vetting the programs. To see if they're going to get the kind of mentorship that they need and not feeling like they have to play the game to be part of this elite brand or insider club, because you can gain access to those things and then be very miserable.

So I really try to help people think about relationships, do some cold emails with would-be advisors and just see how you feel about the reaction you get. But I kind of wonder if that's enough. Aand perhaps as you're saying, everyone has to just learn for themselves and you can't totally protect anyone.

Leslie Wang: No, I think that's definitely the case, although there are tools you can give people to help them assess their situations better. And I typically don't coach grad students, but I took one on recently because I'm friends with her mentor, her mentor is really impressed by her but very concerned about her lack of progress and is actually paying for her coaching.

And I'm very invested in students of color, in particular students from immigrant backgrounds, really being able to thrive in the Academy. And through coaching her, I think, what I always want to offer to people is that they have options, and that one very good option is to leave their program.

I think that that's something that people do not get from their advisors, right? That especially once you've been in it 5, 6, 7 years. And in my program, it was very common for people to take 10 years to finish, because they did these very detailed, lengthy, ethnographic projects that they're trying to turn into books. And there's that sunk cost fallacy that goes along with leaving academia, but it also hits grad students too. And that infantilizing quality of grad school where you could be 35 years old but still sitting on the ground in the hallway, waiting for your advisor to show up. Like it doesn't have to be you, right?

Like you can make a different choice, but if you do choose to do it, you can have a certain a certain I think clarity of mind around why you're doing it. So it really depends on your core values, making sure that the things that you're doing actually align with those. So that the research that you're doing feels like it's somehow being internally motivated and not just, I have to do this for the sake of my next whatever or getting a job or getting an article.

So I feel like a lot of that realignment can happen for folks at any stage in academia, maybe not at the stage where they're applying. Because they don't know yet. They're not in it yet. But once they're in it, if they're really feeling like this is not right, then it's really good to investigate, like, what about it is not right. And what can you change in that? And in what ways can you put yourself first through all of this? And then also recognize that it's a system that's not set up for you to individually thrive per se. So then you have to take other measures into your hands to make sure that that happens.

Joshua Doležal: Yeah, for sure. So you've answered one of my questions about your PhD program, because I was wondering why it took eight years for you, but it seems like that was part of the culture of your discipline and in your program. But then you went to the University of British Columbia for a postdoc and then got the Holy Grail of a tenure-track position at UMass. And you were there how long?

Leslie Wang: Oh, before that though, I took one year tenure-track position at Grand Valley State University in Western Michigan. And then I got the UMass Boston job. So I bounced around.

Joshua Doležal: Wow. So British Columbia to Michigan to Boston. But then you made it, you made it to the big leagues in Boston, essentially, and you made it through the tenure process. You were an Associate when you left, correct? Yeah, so tell me about that process, because I assume that was a very exciting thing for you to get that appointment initially, but then enough of it faded by the end of it that you left. So tell me that story.

Leslie Wang: Oh, where to start? I mean, this is why I don't believe in the concept of dream jobs. I think that it's very misleading to describe things in that way, because it sets up a very narrow idea of what success looks like. And then when it's not that it feels like your world is crushed. So that was basically the job for me was…Boston was a really good move for me.

I already had friends here. I was familiar. There were a lot of people from grad school that were in the area, tons of universities around, easy to network, easy to set up like research collaborations and that sort of thing. I think where I got really disenfranchised though, was with the really dysfunctional structure of my institution. And seeing how little care there was for workers, whether they be staff or faculty, or the many, many adjunct lecturers that teach most of the courses on the campus. It just felt like there just wasn't an ethic of caring for people as human beings and the emphasis was on overwork for not really any particular reasons, because you didn't get rewarded for the overwork. You didn't get higher pay for it. At the end of it, you hope you get tenure. So it was like a very dysfunctional sort of structure in a very dysfunctional department, of which there were many folks who'd been around for 25 or 30 years and had these intense personal grudges against one another that they would pull new faculty into.

And so every hiring committee became highly politicized, pulling people into closed-door rooms to have these chats about… I was like, this is not what I signed up for. Why am I so stressed out all the time? And why is no one helping me figure out how to do things here? And why am I left to my own devices? And so part of it was the department, but I think part of it was just – here's an institution that wants to be more of a research-based one moving away from a teaching service model, but still maintains all the same standards for teaching and service, the same expectations. And now you've got these mega research expectations. There's definitely not enough preparation given to people, because they're not going to say this place is super messed up – good luck. But that's really what it is. And I think many places are like that.

Joshua Doležal: Yeah, I'm sorry to be laughing, because I know that it's really miserable to be part of that. I mean, it's a desperate situation to work in that kind of a department. I'm laughing because it seems humorous to me from a distance now. I mean, I tell this story sometimes…my first semester on a visiting position at the liberal arts college where I eventually earned tenure, there was this longstanding grudge between two of my colleagues and, you know, they were both nearing retirement age. So this had been simmering for many years. And one of them came to my office and asked me what I thought about him proposing to the Dean that he take partial retirement, if somebody else took partial retirement, so they could create a full position for me, like they wanted to keep me.

And I was like, whatever, you know, I didn't want to really have any part of it or make demands on anyone. And it turned out that he blindsided this other colleague with this proposal in a department meeting and asked him, Hey, so and so, aren't you prepared to make a sacrifice for your friend Josh here?

Leslie Wang: Oh, goodness.

Joshua Doležal: And it was really meant to be a gotcha kind of moment. And I'm sitting there as a completely contingent visiting person thinking, Oh my God, this other guy's going to think that I collaborated or colluded or something. And I mean, it was truly a kind of panicked week or two after that, but from a distance now it just seems absurd.

And so there's more than a grain of truth in like the Netflix series “The Chair” or the AMC series “Lucky Hank.”

Leslie Wang: Totally.

Joshua Doležal: That seems just completely hilarious from afar, but when you're living it, it is the worst. It's a kind of hell.

Leslie Wang: I mean, it feels so life or death. And that's the thing is like, okay, the stakes are low from a distance. But when you're in it, it feels like everything. The summer before I even started my position at UMass, I was put on a hiring committee.

And our annual conference is in August and I was asked to go interview candidates. I hadn't started the job yet. So here I'm trying to answer questions about a department I hadn't joined yet. I mean, it's like, what? Why? It's like a waste and it was also very stressful for me because what do I have to say about this place yet I had visited once for my interview. So of course I'm like talking it up and all this, but it's those asks that you're like, what a waste of effort. It's not purposeful.

At a certain point I think it was like, every new thing became like another notch that I was keeping like this very long list of grudges. And at a certain point it was like, there's too many grudges. I can't do this anymore. And of course I was trying to pivot out of my position. I had applied to other ones and I'd even interviewed elsewhere. I don't think I want to leave Boston though. So that does really narrow things down.

Leslie goes on to describe how getting trained as a life coach changed her thinking about the future, how long it took for her to feel ready to leave academe, and how she helps others either make work work better for them in higher ed or prepare for a better life beyond it.