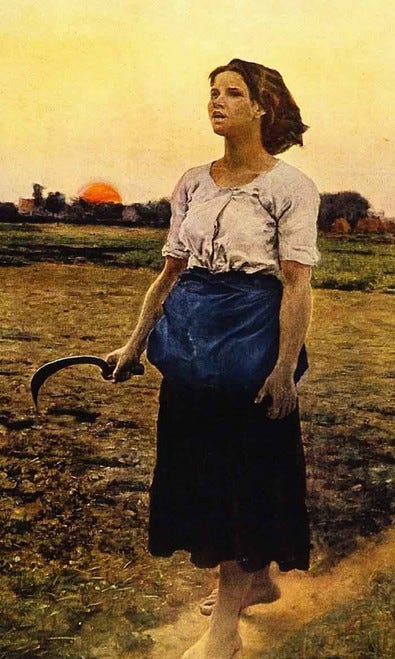

One dream I dreamed a great many times, and it was always the same. I was in a harvest-field full of shocks, and I was lying against one of them. Lena Lingard came across the stubble barefoot, in a short skirt, with a curved reaping-hook in her hand, and she was flushed like the dawn, with a kind of luminous rosiness all about her. She sat down beside me, turned to me with a soft sigh and said, "Now they are all gone, and I can kiss you as much as I like." I used to wish I could have this flattering dream about Ántonia, but I never did.

Download the full reading schedule here.

In my experience, Cather scholars either love or hate Blanche Gelfant’s Freudian analysis of Jim Burden’s dream about Lena.

Gelfant’s essay “The Forgotten Reaping-Hook: Sex in My Ántonia” takes this dream as the foundation of a more nuanced argument about Jim’s self-delusion throughout the narrative. You can read the full essay here. I’ll include a few excerpts below.

Jim Burden belongs to a remarkable gallery of characters for whom Cather consistently invalidates sex. Her priests, pioneers, and artists invest all energy elsewhere. Her idealistic young men die prematurely; her bachelors, children, and old folk remain "neutral" observers… Her characters avoid sexual union with significant and sometimes bizarre ingenuity, or achieve it only in dreams.

Retrospection, a superbly creative act for Cather, becomes for Jim a negative gesture. His recapitulation of the past seems to me a final surrender to sexual fears. He was afraid of growing up, afraid of women, afraid of the nexus of love and death. He could love only that which time had made safe and irrefragable — his memories.

In Jim's dream of Lena, desire and fear clearly contend with one another. With the dreamer's infallibility, Jim contains his ambivalence in a surreal image of Aurora and the Grim Reaper as one. This collaged figure of Lena advances against an ordinary but ominous landscape. Background and forefigure first contrast and then coalesce in meaning. Lena's voluptuous aspects — her luminous glow of sexual arousal, her flesh bared by a short skirt, her soft sighs and kisses — are displayed against shocks and stubbles, a barren field when the reaping-hook has done its work.

To say that Jim Burden expresses castration fears would provide a facile conclusion: and indeed his memoirs multiply images of sharp instruments and painful cutting. The curved reaping-hook in Lena Lingard's hands centralizes an overall pattern that includes Peter's clasp-knife with which he cuts all his melons; Crazy Mary's corn-knife (she "made us feel how sharp her blade was, showing us very graphically just what she meant to do to Lena"); the suicidal tramp "cut to pieces" in the threshing machine; and wicked Wick Cutter's sexual assault.

I have some quarrels with Gelfant’s argument. While Freudian readings have a certain panache, they can hew to antiquated gender and sexuality binaries. Gelfant’s critique of Jim aligns squarely with canards about Cather as a closeted lesbian, a woman in perpetual retreat from her sexual fears. Melissa Homestead has debunked many of these falsehoods in her book The Only Wonderful Things: The Creative Partnership of Willa Cather and Edith Lewis.

However, Gelfant’s study still captures important elements of My Ántonia. John Swift offers as thorough a discussion of Cather and Freud as I’ve seen. Swift traces a familiar pattern in Cather’s art and life: just because she expresses scorn for a school of thought or for an artist, that doesn’t mean her own art doesn’t engage seriously with their ideas. While there’s no clear evidence that Cather deliberately incorporated Freudian themes into My Ántonia, it’s hard to believe that a writer could detail sexual frustration and violence as thoroughly as she does in Book II without responding in some way to Freud’s influence.

As a memoirist, I like to believe that I’m writing boldly into the danger zones of the past with the express purpose of truth telling. But I wonder if there might be a little of Jim Burden in all of us who sift through our memories, if even while we’re searching for truth, we’re also trying to comfort ourselves? 🤔

Now I’d love to hear how Chapters 11-15 in Book II speak to you. I offer a few questions below for each chapter. But I’d also love to hear your independent impressions on these chapters.

Book II

Chapter 11

Cather was a reader of John Bunyan, and she sometimes uses a similarly heavy hand with her character names. Wick Cutter is one of the most chilling villains in her oeuvre, and after hinting at his predatory qualities in earlier chapters, Cather develops his character more fully here as Ántonia prepares to enter his employ. What do you find most memorable in this portrait of Cutter?

The chapter ends with a sentence that reminds me of the unnamed narrator’s dig at Genevieve Whitney in the introduction. Mrs. Cutter seems like a paradox of qualities, possessed of great physical strength but apparently less mental fortitude, in some ways conventionally feminine (with her painted china) but also unconventional in her open defiance of her husband. Yet she seems incapable of leaving him – why? And since she, like Genevieve Whitney, is a rather minor character, why does Jim feel it necessary to take a dig at her?

I’d love to hear your thoughts on this line: “I have found Mrs. Cutters all over the world; sometimes founding new religions, sometimes being forcibly fed —easily recognizable, even when superficially tamed.”

Chapter 12

Jim’s boredom in a small town seems positively quaint by today’s standards, when a thousand distractions beckon from our screens. I’m wary of romanticizing it too much, but Cather offers a useful reminder of how people once sought entertainment from one another in their communities. This brings tedium, as Jim wearies of his conversation partners (including the old German who can speak of nothing but taxidermy). But there is also some charming local color here – snapshots of the fleeting history of a railroad town.

It is curious to me that Jim remains so judgmental of his neighbors, given that he ostensibly recalls these scenes much later in life. Most young people from small towns chafe against those environments at some point, feeling that they are “living under a tyranny.” But can it be true that life in Red Cloud was nothing more than a series of evasions and pretenses? Cather was 45 years old when My Ántonia was published, safely established in New York as a major American author. It’s striking that she doesn’t soften Jim’s view of small-town Nebraska much. Why not?

One of the intrigues of My Ántonia is that Cather perpetually frustrates the conventional romance plot. Lena might allow Jim to kiss her, but the immigrant girls don’t think of him as a potential partner — he seems eternally cast in their minds as a childhood playmate. He tries to punch back a little by threatening to becoming “a regular devil of a fellow,” and he seems smitten by Ántonia, but she rebuffs him while expressing a more motherly love. Why does Ántonia continue to treat Jim “like a kid”? How does his frustrated love for her impact you as a reader?

Chapter 13

Jim’s commencement is another milestone in his coming of age. His speech alludes to Cather’s own graduation address, “Superstition vs. Investigation,” which she delivered at the age of sixteen. Here is the stunning first paragraph:

All human history is a record of an emigration, an exodus from barbarism to civilization; from the very outset of this pilgrimage of humanity, superstition and investigation have been contending for mastery. Since investigation first led man forth on that great search for truth which has prompted all his progress, superstition, the stern Pharoah of his former bondage, has followed him, retarding every step of advancement.

I’m torn about the conclusion of this chapter. On the one hand, it is heartwarming to see Jim’s childhood friends congratulating him. On the other, isn’t it painful to be reminded of the prejudice that kept Anna from going to school? Ántonia and Lena, we well know, could have given their own orations in a different age. Blanche Gelfant might say that Jim’s romantic memories allow us to avoid these uncomfortable historical truths. Do you agree?

Chapter 14

What do you make of the bathing scene, where Jim’s privacy is broken by the girls on the bridge? Rather a curious inversion of the typical gender roles in bathing scenes, wouldn’t you say? Also a strangely innocent scene, given that they are all young adults…

We’ve seen in earlier scenes how Cather often shields her characters from open spaces or harsh elements by creating little sanctuaries for them. In the early chapters, when Jim first met Ántonia, they played in a nest of grass. In this chapter, Jim finds Ántonia sitting in a grove of “pagoda-like elders,” where they each confide memories of Mr. Shimerda that they’ve never revealed to one another. It’s an incredibly intimate scene, isn’t it? I want to quarrel with Gelfant here, because I don’t think sex is necessarily more powerful or more fundamental than friendship. In fact, Gelfant’s reading of Jim as a front for Cather’s sexual fears is an antiquated one which doesn’t allow for a nuanced spectrum of gender and sexuality. I wonder if the relationship we see developing between Jim and Ántonia might resonate with more current parlance about the gender identity spectrum. Or is that taking it too far?

Why do you think Lena destroys Jim’s and Ántonia’s sanctuary at the end of this scene? What effect does that interruption have on the story?

This chapter closes with one of the iconic images of the novel: the plough magnified against the setting sun. Some see this as a symbol that reinforces the myth of the heroic pioneer. Others read it as an illusion, focusing more on the end of the scene, where the plough is “forgotten,” having “sunk back to its own littleness somewhere on the prairie.” What does this image, this scene, evoke for you?

Chapter 15

Gelfant contrasts Wick Cutter’s attack on Jim with the earlier episode, where Jim turns a rattlesnake into a “battered object.” Instead of emerging victorious in this scene, Jim is reduced to victimhood, fearing that his reputation will be sullied by tasteless jokes. He returns home as a “big man” after killing the rattlesnake, but at the close of this scene Jim’s grandmother bathes him (something he didn’t even allow her to do as a child). What is going on here?

Jim’s smug commentary on the Cutters’ dysfunctional marriage recalls the introduction to the novel, where we learn that Jim is also unhappily married. It’s rather rich of him to have such strong opinions about other people when the blush has gone out of his own marriage. Perhaps another reminder of his unreliability as a narrator?

Willa Cather Read Along with Joshua Doležal

Upcoming Reading Schedule

May 17: Book III (all four chapters)

May 24: Book IV (all four chapters)

May 31: Book V (all three chapters)

Thank you, Sadie. May I ask why you see it as a spiritual bond?

The various sexual intrigues in the book don't interest me at all. It is only the spiritual bond between Ántonia and Jim that interests me, and keeps me reading....