If you’d prefer to read one of my essays today, head over to Inner Life, where I’ve shared a reflection on Martin Luther King, Jr.’s classic essay “Pilgrimage to Nonviolence.”

A Conversation with Dr. Leslie Castro-Woodhouse

Joshua Doležal: Welcome back to my interview series with academics who have transitioned to careers in industry or entrepreneurship. I’m Joshua Doležal, and my guest today is Dr. Leslie Castro-Woodhouse, founder and principal of Origami Editorial, where she offers developmental editing and academic book coaching services.

Leslie left a corporate role in marketing in hopes that she would find a deeper “why” in graduate school. She completed a master’s in Asian Studies and a PhD in History, both at the University of California at Berkeley. Like many PhD candidates, she dreamed of becoming a professor, but she completed her degree in 2009, at the height of the financial crisis. After many years of adjuncting and fading hopes for a tenure-track faculty role, Leslie tried to pivot back to industry. But she struggled to find openings in marketing or educational technology that aligned with her values.

So she fell back on developmental editing, in her words, as a Plan C, and later discovered academic book coaching when a colleague approached her for help with his second project. Now Leslie says that editing and coaching keep her connected to her favorite parts of the academic experience: ideation and interesting conversations.

I asked Leslie how she prefers to introduce herself now, which turned out to be a little more complicated than it might seem.

Leslie Castro-Woodhouse: I am both a developmental editor and I call myself an academic book coach. Sometimes writing coach, it kind of just depends on the context. I'm still kind of struggling with the word coach. It seems to evoke different reactions in people. So I'm trying to be mindful of that.

Joshua Doležal: What do you mean?

Leslie Castro-Woodhouse: Well, there seems to be a certain contingent who feel that coach has this association with life coaching. Which is a whole other ball of wax, really. I don't want it to sound like I'm just a cheerleader for people as they write. There's a lot more to it than that. And yet, coaching seems to be the term that just kind of fits the best.

There really isn't a better term than I've found so far. So, I use it in a sort of qualified fashion.

Joshua Doležal: Because we're not really counselors exactly, but something like book midwife would be perhaps overcooked, wouldn't you say?

Leslie Castro-Woodhouse: Or book whisperer. I mean, I feel like the conversations I have when I'm talking to prospective clients, where they're like, so what do we do? What are these hourlong conversations, these sessions about and for and what do we do there? The short answer is, whatever you want. But the longer answer is really what the client needs. And it's part accountability. It's part moral support. It's part actual writing tips and recommending techniques for when people are feeling resistant or stuck or anxious.

And there's actually a lot more of that involved in this job than I ever anticipated. And yet when you take a half step back, the bigger picture is that we are a really compassionate partner, like a colleague who is here for our client, to talk through kind of whatever it is that they're stuck on.

And I know that different coaches have different orientations and some people are more writing oriented and some people are more idea oriented. I love to talk through my clients’ data with them. If they're having trouble finding the narrative and really understanding what their argument is, or they're just not there yet, I've worked with a couple of scholars now on second books where, unlike a dissertation, you don't come in with an existing thing on which to base the book, right?

It isn't a matter of turning a dissertation into a book. You might be starting from scratch, and that's a much different prospect and can be a lot more challenging that way, because also people are out of grad school, they're into their faculty role, they have a lot less time to devote to it, and they don't have the structure that the dissertation, however minimally, may have provided and sometimes they really do just need to start from scratch and start thinking about well, what do I want this book to be about and how am I going to structure this? But to circle back to the original question is we're kind of like the surrogate colleagues that people don't have down the hall from them anymore in their department.

And we're also a much safer bet than those colleagues ever really were to begin with in that we don't look at your tenure portfolio. We are completely neutral party and accept that we are really on the side of our client author, we just want to see them succeed. And that's what we're here to help them do.

We were raised by wolves in my generation. We were left to figure all of this out for ourselves.

Joshua Doležal: I'm going to back up a little bit because this is typically an interview series called academe to industry. And that fits your narrative in a sense, because you moved from academe into your entrepreneurial role. However, you were in industry before that. And so it's a little more complicated. First it was industry to academe. So can you tell me what you did before you got a PhD? What was your job?

Leslie Castro-Woodhouse: Yeah, actually I spent almost 10 years in the world of work, after college, basically in a variety of marketing roles, I mean, my undergrad degree had been visual communications and design, and I started out kind of as a graphic designer and then moved further up the food chain from the person who taking direction from the marketing people to the marketing person giving the direction and I actually got to where I just was really burnt out. I was feeling really overworked and underpaid. I was in kind of an impossible position in my last corporate job and feeling like wow, these corporate types they talk a good game about wanting to know about what the markets are and what their customers really want, but they seem a lot more interested in just getting stuff on shelves and that was the reality, was they were just going to crank out as much stuff to put on shelves as they possibly could and wait to see what worked and what didn't work.

And I found that really frustrating and enraging at a certain point because it was on my back. Like my labor, my 70 hours a week, was apparently worth it, as long as the stuff got out the door onto the shelf, whether it's sold or not that they didn't care about that.

Joshua Doležal: But you were trying to sell it, right?

Leslie Castro-Woodhouse: Well, yeah, my last roles were packaging. So it was doing all the copywriting, getting the photography done, putting a box around a product or many products and consistent branding and working with the design agencies. And it was grueling at times. It was just really a lot. And I really thought at the time that I was fleeing the corporate world for the meritocracy of academia where they would listen to reason, right?

And in a way, even though my career is not strictly in academia anymore, I feel like I still have a foot in it. And the parts that I really like the best, I'm happy to say, are the parts that I still get to do every day, which is to say collegial conversations with people whose work I find really interesting and meaningful and getting that out there into the world, helping promote those voices in the world.

A lot of the problems I identified in the corporate world have now migrated to academia. It's like the layers of bureaucrats at the top and the disconnect with the very precarious itinerant laborers at the bottom of the pyramid.

Joshua Doležal: And the compensation in academe is not anywhere near what you get in corporate roles. But I want to back up just a touch.

So it sounds like you were burned out in your marketing role. You were suffering from a crisis of purpose because you didn't feel like there was a deep and abiding commitment to quality, it was more production and you were, as a marketer, maybe I'm using a regrettable phrase, putting lipstick on a pig at times – there's this product more attractive than it actually is.

And it just doesn't sound like that compensation was enough for you. There was a bad fit. The why of your workplace was kind of gone. Is that fair?

Leslie Castro-Woodhouse: Yeah, absolutely. But then I really always kind of felt like in the corporate world, the why was just not supposed to be important to me. I think there are more folks in the generations coming up behind me for whom why is a much bigger portion of the decision making and some companies have gotten a little more hip to providing workers with a greater sense of purpose, but not in the roles I had.

Joshua Doležal: When did you leave your corporate role?

Leslie Castro-Woodhouse: I was in the corporate world for the 90s. Like I graduated from college in 90 and went back to graduate school at the end, fall of 99. So about a solid decade. And then I was in grad school from 99 to 2009, which was another interesting moment to be in a pipeline and unaware of what was going on outside of it until of course I emerged in the bask and the glow of the dumpster fire that was the 2008 financial crisis and economic meltdown.

So great timing as per usual.

Joshua Doležal: Where did you go and what was your area of study?

Leslie Castro-Woodhouse: I earned my PhD from the University of California at Berkeley, and I started out there in a master's program, an interdisciplinary program in Asian Studies, which I was using as a kind of springboard to figure out which program, which discipline I really wanted to go into.

And at the end of that program, I moved over to the History department and I thought that history would be untouchable as a discipline in the university. I really did. I can't believe that there are now universities and colleges. cutting and actually cutting history programs, history majors and people questioning the value of a history degree.

And at the same time, like on the other side of the room, there were these weird discussions about why don't students have any critical thinking skills anymore? And where's the empathy. And I think, do you not see the disconnect between these two issues? You know, that you keep cutting out all the empathy training portions of the program and wondering why empathy is disappeared.

But if it cannot be directly monetized, I think that is the challenge that many of the humanities face these days. That if it's not seen as directly contributing to a particular career path, especially if it's tech, I mean, STEM has been valorized, right? Until a machine can do your job.

Joshua Doležal: In some of those cases, the social sciences and the data expertise that went along with it, is kind of a nice skill to segue into UXR research, until everybody lays off all the UXR researchers, so that kind of boom/bust mentality is the baggage that comes with a more job skills, jobs based curriculum.

So it sounds like you and I both had a kind of romantic idea of higher ed when we went into it. And for my part, it was the examined life, the pursuit of truths, plural, and all of the things that William Cronon mentions in his classic essay, “Only Connect: The Goals of a Liberal Education.” You try to understand the dreams and nightmares of others.

You learn how to talk with anyone. You learn how to solve problems. It's sort of this really versatile toolkit. It's not just for jobs. It's for relationships. It's for your lifelong thriving. And he was a historian or is still. And so when did you first understand that that was not what was driving your own education as a graduate student?

Leslie Castro-Woodhouse: Ooh, that's a good question because I was always very job oriented. To be honest, while I was in the pipeline, and my department even had its own placement specialist on staff who was there to facilitate PhDs in the department, all their job portfolio stuff.

There was a person to manage this and manage the application and letters of rec and all this stuff. And she had a bulletin board outside her office in the hallway with the names and the institutions after graduation, and I walked by that thing regularly. Like it's going to be me someday.

I had plans, man. I had plans. I was going to be a professor. That was the goal. And it has taken a long time for me to unhook myself from that expectation and from beating myself up for not meeting that expectation. And also to learn how deeply that bias runs within academia that helps to perpetuate that mistaken notion on how closely we hook our identities to our work identities and to what those ideals mean, what those roles mean.

I'm not sure it ever really did change for me as a grad student because I really thought until 2008, when the economy changed, I thought there were jobs, there were academic jobs. And as a UC Berkeley graduate, I thought I was pretty well positioned to get one of them. So I thought when the crisis hit, I would take a couple of years to kind of just chill out.

At that point, I had some other family related things to deal with, a couple of aging parents and some elder care, and some deaths in the family, and things like that, that kind of just ended up sucking up all my time. And diverting me, distracting me from needing to find a job for a while. And I thought it would come back, and it never really did.

And from about 2010, 2015, I mainly did adjuncting around the San Francisco Bay Area, where I was living, and I got some roles at UC Berkeley as an adjunct. The University of San Francisco across the bay. And eventually that was where I found my first editing role, was at USF. The small, Asian Studies journal where I became managing editor on a part time basis. And this was kind of my first putting my foot in the pool in terms of really identifying a different arena where I could potentially find a career path. The market wasn't there anymore and I had to figure out plan C.

Joshua Doležal: I don't know if as an adjunct you became more aware of these corporate dynamics in the university or if that's only become clear to you from a distance now that you're out?

Leslie Castro-Woodhouse: Oh no, definitely the adjunct experience was hugely informative. The fact that you could be sharing an office with like four or five other adjuncts, or a desk with four or five other adjuncts. The way that you're treated by the other faculty. And at the same time, you're really nicely jerked around by the university.

There was one semester, I really freaked out because I got called up for jury duty about a week before I was to start this adjunct position at Berkeley. This is at Berkeley. And I really, really wanted to do it, needed to do it financially, but I had absolutely no documentation to show the court that I was actually going to be employed.

And so I had to sit through a jury selection process. I got all the way in the jury box before I finally got selected out. But I just was in terror for a week that I was going to lose my adjunct job because I couldn't even demonstrate that I had, this was a real thing. This was a real job. They didn't even have an offer letter for me.

And it turned out once they finally sent me all the union documentation in the handbook, Oh, I could actually have gotten that time off legally. They had to give that to me. I did not know. How would I have known? So it just really, it really drove home how it's all on the adjunct. It's all on this poor contingent person to figure out so much stuff, and it's just really unfair and uncool.

Joshua Doležal: What a position to be in, that you were sweating it out, caught between these two bureaucracies. You couldn't really say no to either one. And neither one was going to consider your best interest. And what a perfect metaphor for adjunct and contingent labor.

Leslie Castro-Woodhouse: Yeah, I mean, I might have lost the crappily paying adjunct job for an even more crappily paying jury duty gig. Like what is that, $3.50 a day or something?

Joshua Doležal: The sad thing is that both of them are very important. One, without it, the university would crumble. Because these are essential experiences that you're providing. And the other is – what's more basic than your right to a trial by a jury of your peers?

The fact that you were feeling jeopardized or exposed by both is a sad commentary. The percentage of courses taught by adjuncts is continually growing. It sounds like a similar situation to corporate America in the 90s where it's about getting stuff on the shelves and packaging the brand and the marketer or the professor is kind of not important.

Leslie Castro-Woodhouse: Yeah. They're just sort of the delivery mechanism. It's become very transactional, transactionalized. I kind of see this as a more widespread social problem as well, that our society has also become very transactionalized, but that isn't the focus of this interview.

Joshua Doležal: Well, it kind of is because the why that was disappearing from your corporate job became the same why that was disappearing from your higher ed jobs, right?

I think I have a sense of why you pivoted. Why didn't you go back into industry where, as I'm doing all these interviews with other people that are talking about upskilling and the job search, like you would have had a huge head start with all that because you already had the resume, you could have gone straight back into marketing.

Leslie Castro-Woodhouse: Well, I thought so anyway, but it turns out corporate marketers don't really like people like me very much. I don't want to say PhDs. I think there probably are PhDs they'd be very happy with. I think that my main problem. Because I did try to go back in the industry. I really did. I really tried. I tried so hard.

It was really demoralizing. Because I think that there are a lot of companies I applied to, roles I applied to, for which I was frankly overqualified and that was a non-starter. But I think the bigger, deeper issue for me was that truly, I didn't buy it. That if it was a UX role, it was an EdTech role, frankly I felt like, aren't these part of the problem?

I don't want to be part of the problem. I don't want to be monetizing educational technology. I think educational technology needs to, frankly, be a lot more invisible. You know, it should be more about education. It's kind of extractive, it's exploitive. It's about making money off of things and people in ways that I just find icky.

I just don't like it. I don't want it. I don't want to foster that in the world, is what it really comes down to.

Joshua Doležal: How did you first become aware of coaching as a possibility for you? And then how did you make that transition?

Leslie Castro-Woodhouse: Completely by accident. I mean, I was early in launching my editing business and I thought that being an academic copy editor was probably a pretty decent pathway to pursue. And I have some folks in my circle, my existing network who were interested in, getting their stuff edited. So there I was, but it was not long after I kind of hung out my shingle that a friend and colleague reached out to me and said, Oh my God, Leslie, I'm so glad you're doing this because I need help. Like, I have this second book, and I don't know what it's about. Like, and I've been gathering data, and I have data, but I'm not really sure what it says. I haven't really unpacked it yet. But here's my initial ideas. And he sent me a very uncooked, I won't call it a manuscript, but it was some writing, where he was trying to hash out his ideas on, what, what he wanted to write about.

And I could kind of get an impression of what he was after, but it wasn't there yet. It needed a lot of development and so that was the point at which I said, sure, I would be happy to just meet with you on an ongoing basis and help you figure this out.

I didn't know that was coaching. I didn't know that was book coaching at all. I didn't know it was a thing, but then I also didn't even know developmental editing was a thing until I realized, oh, that's what I'm doing. I'm doing this thing and wow, there's a name for it. I just kind of felt like it hit the sweet spot for me of like my favorite parts of the academic experience.

And yet it's not like, it's not classroom teaching and it's not doing my own research and writing. And yet, having been in those contexts informs directly the profession, the practice of doing what we do. I want to talk to people who are still ideating, who are still brainstorming what the book is about.

That's great. I love that part because I love talking about the ideas with my authors in addition to talking with them about how to stay motivated and how to set goals that will keep them moving along the way and actually reflecting on the actual texts that they write. Once I got into it, I realized, wow, how much there was in this arena to do that was a value to my peers. And it was something that I feel like, wow, I've been, I've been trained to do this all along.

Joshua Doležal: Several colleagues in the coaching space have a similar origin story. One came to coaching while she was being coached – her coach saw potential for her in the same pathway. In my case, I was offering an online creative writing course through a Dallas-based organization called Writing Workshops and like you said, it was accidental.

I didn't intend for there to be any workshop element to the course, because I was thinking of keeping my own labor low. But the students wanted that. And so I organized a pop-up workshop at the end of the course, and then gave them all feedback as I normally would in a college class. And it was a revelation for some of them. They'd never had their work seen that way with such care. And so they approached me and said, do you offer coaching? And I never considered it, but for them, I said, sure. And one of them is still a client. So that was my first awareness that there is this field. For me, the word is, I'm a teacher.

I don't know that I'm a coach. I'm an editor for sure, but editing is just one part of teaching. So really it's working through the entire writing process. As you say, the planning stage is so important. What's the larger vision for the project, the core set of questions driving it, or when you've resolved it, if it's a memoir, what's the big turning point that you're working toward. And, you know, scaffold everything accordingly.

So those are things that I would have spoken with my students about on the essay level. Now it's bigger. And your comment earlier about the colleague down the hall, I think is a really insightful.

In your case, being an academic book coach and in mine, being a more of a literary book coach – we are being paid for that kind of invisible labor that's often part of professional relationships in academe. What do you think you bring to your clients that they don't get from, let's say it's not the colleague down the hall, but it's someone that they know through a professional organization and their little writing group or whatever that exchanges drafts. What do you offer that's greater than that?

Leslie Castro-Woodhouse: I would have to say that really at the top of the list, safety – a sense of if the ideas aren't cooked yet, that's okay. They don't have to worry that I'm a colleague who's going, Oh my God, is this person for real? Like where did they get their degree? Like, I can't believe I already signed off on that dissertation. Oh my God.

No. I am their ally. I am on their side. And I'm surprised at how much space that that unlocks in terms of their writing practice and developing ideas, that just knowing that there's somebody you can talk to who's trained like you, who knows this language. Because it is really a language, right? This academic language.

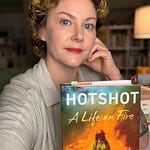

But in addition to the safety and that space of safety that my coaching relationship affords, I think the next big thing is the perspective of working with a bunch of different scholars. And seeing how actual published things work, having been on the other side of that desk and having that professional experience to bring to the process, and also that I've published my own book.

I've been that scholar trying to whip the dissertation into shape to make it a real book. And I know what that feels like. I know what it's like to be rejected, I’ve been through all of the pieces. And so I really know what it feels like to be in my client's shoes.

Joshua Doležal: What do you see as the future of your practice? Why do you feel that this is a sustainable area for you to continue investing in professionally?

Leslie Castro-Woodhouse: Well, to be honest, I have my moments when I'm not sure. But then, it's still a very young practice and I need to be a little less hard on myself about like, I should have a million clients right now.

It's a practice and I'm trying to build it still and testing out whether it's really long term, sustainable, and viable. But what I am finding is that particularly amongst the current generation of scholars who are kind of like newly hatched from grad school right now, there seems to be a much higher willingness to say, you know what, I need help. And I am looking for a professional to help me with this.

Whereas for my generation and people behind me, like what? You can't have somebody else telling you what to write. I'm not telling anybody what to write, but the idea of having, the availability of help and it's that it's acceptable to ask for help, I think is the big shift that I'm seeing. And I think it's a good one because we were raised by wolves in my generation. We were left to figure all of this shit out for ourselves. And it's not easy, nobody taught us how to write or how to think. And they're still uninterested. In many cases, even our dissertation advisors, once we're hatched, we're gone. Bye bye, see you later. And you're on your own and who's out there to help new faculty and people in these roles?

Even people who've got tenure are still looking for, like, I need more accountability and I just need help, maybe if I'm paying someone for their time, I will take the project seriously. I will stay on track with it. So I think there are some cultural shifts.

I like the control that I have over my time, over my clientele, but also that I really get to live my why and support the kinds of projects and people that I want to see and encourage in the world.

Joshua Doležal: The impulse for writing, even in academe is to be heard, to connect, to know that you're not alone. And so, as you say, for our generation, it was much more of a stiff upper lip. Figure it out. And if you can't, then you're not worthy. And so in this case, it's like anything else. If you want to get better, having support and resources will help you do that.

Leslie Castro-Woodhouse: It's actually a role I really love. I didn't expect to; I thought that editing was sort of a plan C, after industry doesn't work out and academia doesn't work out, NGOs don't work out, where are you?

And now I find that working for myself is where I really like to be. I like the control that I have over my time, over my clientele, but also that I really get to live my why and support the kinds of projects and people that I want to see and encourage in the world. That's what it really comes down to is, yeah, I could make more money. I could. Hopefully I will. But I just need to survive. I just need to support myself and do okay. I don't need to make a gajillion dollars and I'm not interested in that. So this is a very fortunate pathway for somebody like me who would otherwise be doomed to obscurity and poverty.

Joshua Doležal: Well, I'm so glad to hear that you've returned to your why. That's the most important thing that's sustaining you. I wish you all the best in growing your practice! And, hopefully a reader or two of mine will reach out.

Subscribe to The Recovering Academic

Unlock more essays, poems, interviews, and craft resources.