Episode 6 Transcript

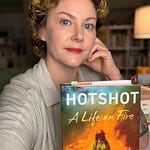

Joshua Doležal: I’m Joshua Doležal, and this is Catchment, the podcast for The Recovering Academic Substack series. My guest today is Dr. Ginger Lockhart.

Ginger and I connected through LinkedIn, where I’m finding more recovering academics than I expected. And the idea of recovery is more than a metaphor for many of us. Ginger told me that her addiction to achievement as a young person is what led her to the PhD originally, and that as an entrepreneur she now guards against that mentality. Ironically, she is able to achieve more as a business owner by making herself less visible.

Ginger Lockhart: I don't want to use the term addiction because that is a serious problem. But as somebody who has had problematic behaviors related to achieving things, I tend not to talk about it too much publicly. I just try to work behind the scenes as much as I can. And that is a much more full way of achieving job satisfaction for me.

Joshua Doležal: Ginger Lockhart earned tenure at Utah State University as a quantitative psychologist. She says that much of her work felt like pulling teeth: teaching students who didn’t want to take her required courses. And she struggled with the reality that many low-income students were accumulating debt without even completing their degrees. Everyone told her that she just needed a sabbatical, but when she found herself dreading a return to teaching after a year away, Ginger knew something had to give. During the COVID lockdowns, she and her husband experimented with an online workshop on a popular software for researchers, and when the demand far surpassed their expectations, the idea for QuantFish, a statistics training platform for researchers, was born. Ginger and I cover a lot of ground today, including the challenges that working moms face, the unlimited potential of the creator economy, and the surprising progress anyone can make by taking action for just five minutes a day.

In addition to the full episode for paying subscribers, I’m sharing a free sample of my conversation with Ginger. To hear the full interview, you can upgrade your subscription at joshuadolezal dot substack dot com, slash subscribe. Or just click on the subscribe button in the podcast transcript. Your membership also gives you access to my full archive and member-only content, like stories for The Chronicle, interviews with academics who have transitioned to industry, private discussion threads on Fridays, and literary work that I share throughout the year. I look forward to welcoming you to The Recovering Academic community.

Now back to my conversation with Ginger Lockhart.

Joshua Doležal: Well, there's quite a community of us. It's been heartening on Substack and LinkedIn to see so many ex-pat academics or recovering academics, whatever the term is. What's your preferred term?

Ginger Lockhart: I like the term ex-pat because it really does sort of feel like you moved to another country when you leave academia to anything else. It's just a very special culture and I felt like I was going through adolescence again. I had to learn some pretty basic stuff coming out of there and unlearn a lot of things too.

Joshua Doležal: Well I was speaking with the dean of the medical school here at University Park and he's retired Navy and he was talking about the identity shift, you know, from the military to civilian life and you really are outside the fishbowl looking in, was his metaphor. So there are a lot of those that fit.

Ginger Lockhart: Yeah, that's true. The military is a good comparison too, I think. I have a lot of military family members and of course they don't get very much attention. I think there's been a lot of attention lately on academics who are transitioning out because I think we tend to be sort of louder about our experiences maybe. And so there's this whole literature, of course, the quit lit and all this other stuff and there's no quit lit for my cousin who just left the military and wants to open a barbershop because nobody cares.

Joshua Doležal: I want to rewind a bit, because…I guess some people grow up with academe on their radar from a very early age. I don't know very much about your early chapters and sort of what that path was like for you, but it's kind of an unlikely one and all of us hear those warnings about being overqualified if you get a PhD and we kind of ignore those to some extent, I think, to accept that as our path. So you know, what were the earliest sources of that for you, and why did you make the choice to go on for PhD eventually?

Ginger Lockhart: I guess it wasn't really on my radar until I was in college as an undergraduate. So my parents you know, they were both in the military. My mom was a nurse and my dad was like a surgical tech, which is somebody who helps in an operating room, and they met there in the military and just kind of went through the structures along the GI bill and this was all during peace time. So I'm very fortunate that my parents were never deployed. And so college was always in the air for me. I thought of it as the next logical step after high school. And I had gotten it into my mind that I wanted to go to medical school. And that's because I really thrived on, I liked achievement and became over time sort of addicted to the feeling that I got from achievement. And medical school sounded like the sexiest thing that I could come up with that, you know, I could kind of tell people that I was doing next. But it became pretty clear to me after, you know, volunteering a couple of stints in hospitals, that that was not a good fit for me on any level whatsoever. First of all, I could not get past the smell of a hospital. And when I say I couldn't get past, I just really my head would just fill with clouds. It wasn't a really a bad smell. It's just this sort of special combination of bleach and gauze. And maybe it's just a slight amount of urine. I don't know what it is, but it is just really got me where it hurt. So the other thing too was that I thought just vaguely that I wanted to help people and this was the most prestigious way that I could do that. And I didn't feel helpful in this situation. And I talked to a lot of physicians too, and many of them were pretty unhappy with their jobs. They would rather be doing honestly anything else, many of them. Which is also very sad, right? So this, you would think of this as, as a high satisfaction type of job. And it could be because these were hospitals and that is the culture in hospitals and maybe it's different in clinics and things like that. So yeah, that happened.

And then I was in a research methods class. So in research methods, this is when you sort of get the grand tour of the scientific method and you have to produce a fair amount of writing. And I had a really wonderful professor who wrote on a paper that I submitted something to the effect of “I'm impressed with your writing and your analytics skills. I hope that you consider graduate school someday. And I would love to talk to you about it. Why don't you come by my office when you can.” And so that's what I did. You know, I was 20 or something like this and I didn't really even know what graduate school, what that meant to go to graduate school. So at the time I thought, okay, that just meant that I was going to scoop up a thing that'll be the next feather that I can put in my cap and the thing that I can tell people that I'm doing. So that was a motivator. But the other motivator was simply because I really liked this professor. That sounds pretty silly, you know, to make this huge life decision based off of a note that a professor wrote on my paper. But I just really loved learning from her and respected her deeply. She's a brilliant researcher, still is. Yeah, she connected me with other professors on campus. And so I got started working in their labs doing sort of applied developmental psychology. So we were collecting data on kids and their experiences with relationships and education. And so I wasn't necessarily ravenously curious about the topic, but I really loved the people that I worked with, because I mean, they just took genuine joy in finding people who had the raw talent and bringing them into their circle and training them to do what they do. And I kept kind of going along with it. I never really consciously sat there and told myself, I am not that into this. It's not that I wasn't interested in the topic, I wasn't interested in the method that goes along with learning the topic. Because, you know, my mind just doesn't really work that way. And even without the bureaucratic red tape and all the nonsense that you have to go through in order to do research, I still could not be motivated to follow along the snail’s timeline that is involved in collecting human subjects data and doing analyses on those data. By the time, you know, a study is completed, my brain has already moved on to many, many other things. And this is not something that I'm terribly proud of, it just is what it is. I just have to move on at a faster rate in order to feel invested in it. So by the time I was finished with graduate school, I thought, shit, what am I going to do now?

So then I found this postdoc. So I went to Arizona State University and got my PhD in human development. So it's an applied developmental science. So it's sort of like developmental psychology, but more contextual. And at the time that I was graduating the job market was really, really slow. This was like kind of right at the beginning of the previous economic crisis that we had with the housing bubble and all that good stuff. And so a lot of universities were responding by not hiring. So I knew I needed to kill more time. And of course, knowing me, I was trying to find what is the most prestigious way that I can kill more time. And so I got a postdoc in quantitative methods at Johns Hopkins. And so that at the time was the best place to do that. So this was specifically being trained in a branch of, of statistics that is designed to discover ways of measuring things in prevention science. Prevention science generally speaking is just the sort of art and science of keeping bad things from happening to people. Whether that's mental health problems, physical health problems, social problems. And so there are a lot of tricky statistical situations that go along to that because you can't randomly assign people to bad things for example, and then see what happens to them. So you have to devise different techniques to measure those processes. And I knew that I could do it. I am good enough at math to sort of be able to pull it off. But it takes everything I have, you know, like I can't socialize and, and I can't have hobbies, you know, and I definitely can't have kids. And those are people that came later. But during my postdoc, that's what I did. Both of my postdoc trainers were wonderful people, and that's what made it tolerable, was that they were wonderful people who took unbelievable amounts of joy in training me to do the thing that they do.

Joshua Doležal: Well, as you're talking, if I can just kind of say back some of this, I think your term achievement addiction is very common among academics. The CV and the…when I was speaking with Liz Haswell a couple of weeks ago, or last month, she numbers her publications. It's not something I did, but I was highly aware of every notch on that CV. And then the other thing you're saying is that the work itself is totalizing. When we think about totalizing institutions, they really ask everything of you. And there's no space really for family life or anything else. But I'm also struck by what seems like a very human story of responding to mentors. You know, and that's, I think, something that we're evolved to do, is to respect elders and, and take advice from people who have more experience and who are more seasoned. Who I guess, in hunter-gatherer times, would be trying to protect us from risk. We would trust them and their judgment. And so there's no way that you could have necessarily countered that, right? I mean, how would you have known otherwise?

Ginger Lockhart: No, I guess I wouldn't, and this is all, I mean, I didn't really have any degree of clarity until maybe like a year ago on kind of what was going on with me mentally and why it is that I kind of went through all this schooling and two postdocs and the tenure track, knowing that I didn't really want to do it. Because I think being a kid in the eighties, there was just like this sort of background teaching philosophy I think that was going on that was really rooted in developing self-esteem. And so there was a lot of external showing people that they're special, right? And so I was able to sort of get that niche when I was a kid of the smart one in the room. And I liked that, right? And so it made me feel like I sort of belonged to something, you know, the sort of higher up the echelons that I would go even though I didn't really, because I mean the very basics of it are that you should at least be into the thing that you're studying, right? But that wasn't it. I was into the people who were nice enough to usher me through. And I just want to say this again, I'm so grateful for them. I don't have regrets. I'm extremely lucky to not have any serious regrets about any of it. But I did use up a lot of years kind of chasing after things that were not helpful. So I'm still pretty, it's still sort of coming out of it.

Joshua Doležal: Yeah. Well, I hope it's not triggering for me to ask about it, but in my own case, I've thought about this quite a bit. You know, my grandfather worked at a sawmill all his life and was proud of being a hardworking man. And, you know, provider for his family and all those things. But he didn't have any fondness for his bosses. There are no country songs about good bosses. He was a union member and I visited him in his lawn chair when he was on strike for better wages, so there was definitely this sense of independence and no, I'm going to look out for myself. I have this job and I'm glad I have it, but not to the point of prostrating myself or groveling before my employer. I'm going to stand up for myself too. I feel like so much of that used to be the spirit of academic freedom as well. I really responded, I think, to that culture in academe because it seemed so similar to this independent spirit of my blue collar ancestors and mentors, role models. And then I was in a community where everyone was scared to death to say what they thought because they thought they'd get penalized on tenure review or something. And it's just like, really? So to become a privileged person means that you must be terrified, insincere, put up a false front. All of that really just rankled over time and I found it kind of unacceptable.

Ginger Lockhart: Yeah. Yeah. I'm right there with you. I picked up a lot of behaviors, especially as a professor, that really made me dislike myself because I was one of them, you know, I was one of the quiet ones. I was told by one of my mentors, not one of the ones that I mentioned, but that as an assistant professor, you sit in the back of your faculty meetings and you drink your coffee and you don't talk unless you have some sort of supportive thing to say about one of your senior members. And so I sat in the back and I drank my coffee. I also as a teacher, so I taught statistics and research methods, realized very quickly that we were there to serve a customer base and we weren't really there to teach them. And so I started handing out A’s and B's like they were pieces of candy as a self-preservation mechanism. And so that really made me dislike myself too. So there I was not saying things that I knew to be true and handing out rewards that people didn't earn. And that was sort of the beginning of the sort of stomach churn that caused me to walk.