How many first-generation students were not the first?

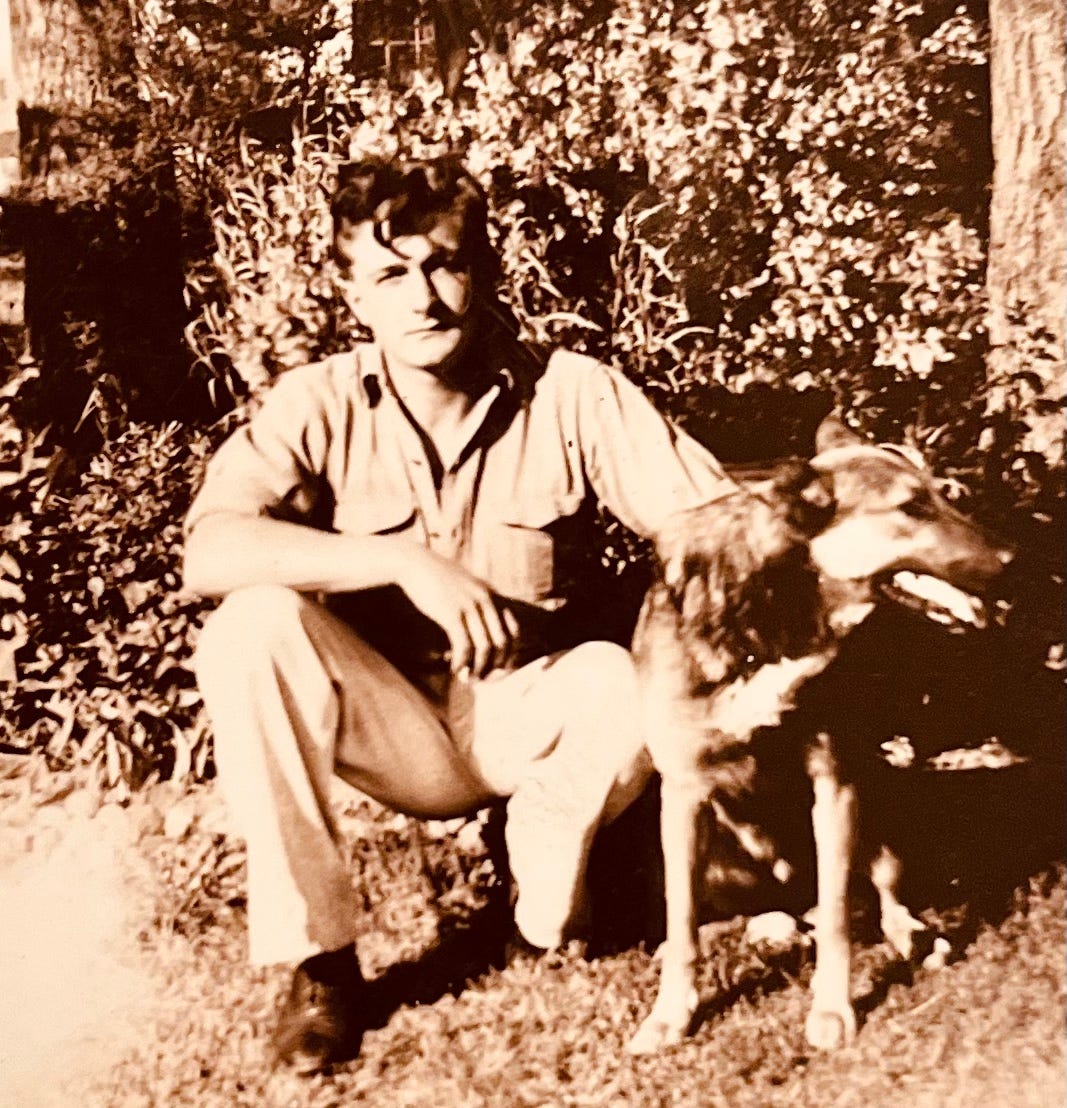

Reading the silences in my grandfather's life

Soon after I left academe, I found myself probing my family roots. It was a way of feeling less alone, imagining my journey as a kind of emigration that ec…