The cult of positive thinking comes for academe

Barbara Ehrenreich warned us this would end badly

Last July, while living in a studio apartment in Prague, I began reading Václav Havel’s Disturbing the Peace. Line after line from Havel jolted me with familiarity, only I had never lived under Communist rule — I had worked in higher education for sixteen years. The result was “Academe Is Suffering from Foreign Occupiers.”

I had a similar awakening last week while rereading Barbara Ehrenreich’s Bright-Sided: How the Relentless Promotion of Positive Thinking has Undermined America. Like Havel, Ehrenreich notes the ironic similarities between the corporate wasteland and the hollow states produced by communist censors and propagandists.

While she makes passing reference to the corporatization of universities, Ehrenreich takes particular aim at “pastorpreneurs” like Rick Warren and Joel Osteen, whose embrace of positive thinking has effectively flipped their church’s priorities: instead of building a church upon a theological foundation, they begin with extensive surveys of their prospective parishioners/customers and build the church upon what the people want, much as this addle-headed column suggests we ought to do with universities. Millions of dollars are spent every year on consulting advice based on the upside-down notion that students “hire” a university and that the institution therefore needs to be gutted and remodeled to attract these fresh-faced “employers.”

I’ll return to the haunting similarities between mega-churches and universities presently, but first I must establish what Ehrenreich means by positive thinking, why she believes it has wrought such harm on American culture, and why I believe her case for certain strains of negative thinking is as germane to higher education now as it was to business when her book was released in 2010. Business fads seem to have a delayed impact on higher education, the way that American pop music spreads to international audiences a decade or more after its peak. This ought to allow academics to learn from failed experiments in industry, but as I read on in Bright-Sided, I grew increasingly convinced that universities are largely duplicating the mistakes of their corporate forebears.

Positive thinking began as the antidote to Puritanism

Ehrenreich describes the Puritan roots of American culture as “a system of socially imposed depression.” Young Goodman Brown, of Hawthorne’s eponymous story, captures the idea best. Brown is so traumatized by his dream (or memory) of a Satanic tryst in the forest, where he sees all of the holiest people gathered around a sacrificial pyre, that he thereafter distrusts everyone he meets. Goodman Brown’s story ends with torpor: “And when he had lived long, and was borne to his grave, a hoary corpse…they carved no hopeful verse upon his tombstone; for his dying hour was gloom.”

Positive thinking was the nineteenth-century remedy to Brown’s soul-sickness and the bourgeois variation on it known as neurasthenia. But American-style positive thinking is not to be confused with optimism: it is, as Ehrenreich explains, a “practice, or discipline, of trying to think in a positive way.” Ralph Waldo Emerson ritualized one form of it in his high-flying essays, and Mary Baker Eddy offered a more popular version in her Christian Science movement. Emerson claims, in the final lines of “Self-Reliance,” that real freedom means authoring our own destiny, not allowing ourselves to be buffeted by good or bad fortune: “A political victory, a rise of rents, the recovery of your sick, or the return of your absent friend, or some other favorable event, raises your spirits, and you think good days are preparing for you. Do not believe it. Nothing can bring you peace but yourself.” Likewise, Eddy preached that disease was an illusion produced by a weak mind.

It might be liberating to imagine yourself capable of willing success and happiness into your life, but the ironic upshot is a different form of Puritanism: personal blame for bad fortune. This ideology — the belief that visualizing success can become its own form of predestination — turns toxic in the workplace. Ehrenreich boils it down to a syllogism: “If optimism is the key to material success, and if you can achieve an optimistic outlook through the discipline of positive thinking, then there is no excuse for failure…. If your business fails or your job is eliminated, it must [be] because you didn’t try hard enough, didn’t believe firmly enough in the inevitability of your own success.” To a Calvinist, you might be pitiable if unconditional election passed you by, since you would quite literally be damned. But at least in that case you could not have been expected to do anything about it either way. The American who gets a pink slip is even more of a loser by the standards of positive thinking: not just damned, but damnable for not having forestalled their own firing through sheer force of will.

But salvation is possible even for those who have been shown the door, if they take no time to grieve their loss or question the circumstances under which they were let go. This trick is achieved by embracing change and thereby finding the opportunity hiding in every crisis. The classic text for this socially sanctioned form of denial is Spencer Johnson’s Who Moved My Cheese?, which contrasts two mice (Sniff and Scurry) with two tiny humans (Hem and Haw). All four are searching for cheese in a maze, but the humans despair when their cache runs out, while the mice just keep moving and find new curds to nibble. Ehrenreich translates the takeaway: “Lesson for victims of layoffs: the dangerous human tendencies to ‘overanalyze’ and complain must be overcome for a more rodentlike approach to life. When you lose a job, just shut up and scamper along to the next one.”

How positive thinking enables gaslighting in academe

Strategic planning is one of the primary ways that college administrators apply corporate-style positive thinking to higher education. Long-range thinking can be a real asset to an institution, and it comes naturally to scholars trained to cover large swaths of history or to track echoes of history in the present time. But typically academics prefer retrospective analysis to predictions, because the former is more evidence based. The kind of forecast that feels most honest to a scholar is often negative, such as a warning about the implications of normalizing fascist rhetoric or a work like Jared Diamond’s Collapse. If you foretell the worst and it does not come to pass, generally everyone is relieved. But no scholar that I know wants to feel like a carnival barker making inflated promises.

By contrast, bold predictions allow college presidents, deans, or aspiring deanlets, to burnish a personal brand. Another word for such predictions is “vision,” as in “I have a vision for the future of this university.” There is almost no incentive for a college leader to offer a more measured view; if the vision falls flat, it can often be blamed on uncooperative or insufficiently buoyant subordinates. The only real consequence might be a premature departure.

Those leading strategic planning are rarely the ones who will live with its aftermath, which is why the default faculty response to executive visions is either outright skepticism or a version of “Trust, but verify.” One might even say that distrust is the more empirical mindset. The high rate of turnover among college leaders directly parallels the upheaval among business executives since the 1980s. The average tenure of a college president, a decade ago, was about 8.5 years. By 2016 the average had dropped to 6.5 years, and now some experts say that presidents only last 3-5 years at the helm, which is roughly the same range as for academic deans. Ehrenreich notes that because senior managers enjoy stock options and often have golden parachutes built into their contracts, they can expect to strike it rich (by most Americans’ standards) no matter how market turmoil shakes out: “The combination of great danger and potentially dazzling rewards makes for a potent cocktail.”

Whereas corporate CEOs once rose through the ranks of a company to senior leadership, many executives of the 90s and 00s looked more like motivational speakers than seasoned businesspeople. Dennis Tourish and Ashly Pinnington capture the trend in a 2002 article exploring cultic elements in transformational leadership. The dark side of “charismatic visionaries,” Tourist and Pinnington say, is a “monomaniacal conviction that there is one right way of doing things.” Such leaders come to believe that “they possess an almost divine insight into reality.”

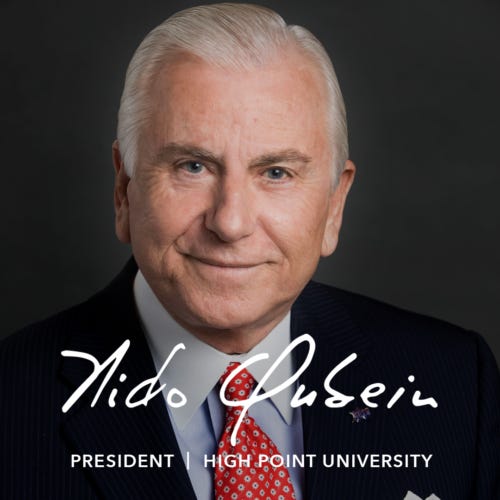

Pick a university, any university, and browse the pages devoted to its president, and chances are good that you’ll find a biography short on academic bona fides and long on inspirational and aspirational rhetoric. The most dramatic example might be Dr. Nido R. Qubein, President of High Point University. The pages devoted to the “Office of the President” include dazzling charts and graphics illustrating how he has increased enrollment by 250%, grown faculty/staff positions by 394%, and expanded the campus footprint by 449% since his hiring in 2005. These are nearly superhuman achievements, a point that Qubein’s biography frequently emphasizes. Even during the Great Recession, even during a global pandemic, he was able to attract more students and donors, swelling the university’s coffers from a measly $56 million to nearly one billion dollars.

What you won’t find in Dr. Qubein’s biography is any depth of historical knowledge, cultural sophistication, or philosophical curiosity. That may well be because his doctorate is an honorary one — his highest earned degree is an M.S. in business education. He is the author of books such as Stairway to Success (1996), How to Get Anything You Want (1998), and Attitude: The Remarkable Power of Optimism (2013) — all volumes that nakedly endorse a transactional view of education. I don’t know enough about the culture at High Point University to say whether faculty there feel that having more resources has empowered them to nurture the life of the mind, but I suspect that even if my department were flush with cash, I’d be uneasy with a leader who feels more at home on a set with Dr. Phil and Oprah than he might on a panel with, say, Noam Chomsky or Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie.

There is something Icarus-like about Qubein’s story. Exponential growth like that must end before it topples under its own weight. The historical analogues to such limitless ambition include sunny promises like “Rain Follows the Plow,” which might have been rewritten a generation later as “Dust and Ruin Follows the Plow.” Even if a college leader offers a more modest vision for the future, scholars who study the rise and fall of empires are likely to wonder what the implicit tradeoffs might be in a new plan — whether disruptive change is necessary, or necessarily better than an imperfect status quo. Such caution is often interpreted by executives as resistance, which is when the gaslighting begins.

Patrick Hamilton’s 1938 play Gas Light, also produced in America as Angel Street, features an abusive husband who manipulates his wife into thinking she is going insane, largely by questioning her perception of reality. The gas light in their house is not really dimming, for instance; she just imagines that it is. University leaders practice gaslighting when they undermine the legitimacy of faculty concerns or elevate themselves above the campus community with such canards as “I’ve never been at an institution where X happens” (translation: this place is provincial and I’ve known better).

Sometimes the parameters for strategic planning or assessment are even subtler versions of gaslighting, because anyone who questions the premise must choose between outright defiance, unwilling participation, or passive disengagement. Take, for instance, the task my department was once given to overhaul our mission statement and curriculum with an eye toward where we wanted to be in ten years. This was part of a campus-wide effort, and we regularly heard specious messages about how we needed to be preparing ourselves to reach present-day third graders. My eldest daughter was a third grader at the time, and I couldn’t imagine how, exactly, anyone could anticipate what her interests or learning needs might be in ten years, much less what imperatives current events might bring to our curriculum. It wasn’t obstinacy that made me question the premise: it was intellectual humility. Who was to say that even the best laid plans might not miss the mark? Why not double down on what we knew had served generations before?

No one was talking about ChatGPT then, and the ongoing angst about academic integrity for college-level writing can scarcely be blamed on a failure to plan. Executives who may well be gone in two or three years can benefit greatly from being perceived as responsive to national tragedies like George Floyd’s death or ongoing struggles over censorship and free speech, such as those presently roiling Florida. But there is a difference between pedagogical agility in connecting to current events and the more radical forms of systematic disruption that charismatic leaders often encourage. Who is to say that decolonizing the university or abandoning traditional grading is going to stand the test of time? Besides, third graders are individuals, not necessarily a cohort, and it would take some real hubris to claim to know what they might need or what disciplines will be most in demand when they reach college age.

As it happens, my daughter (now a fifth grader) loves Greek mythology and musical theatre every bit as much as she loves biology. After reading the juvenile forms of mythology popularized by Rick Riordan, she recently scoured my office for a dog-eared copy of Edith Hamilton’s tales of ancient gods and heroes because, in her words, it was the real thing and not just snarky comments. I would not be surprised if one day I discovered that she had absconded with my copy of The Golden Bough. During a recent hike, she regaled me with an unabridged version of Perseus and Medusa, and as much as I enjoyed it, I could not beat back intrusive thoughts about university leaders who are systematically gutting the very departments that would allow my daughter to flourish. There is nothing juvenile about my daughter’s interests: many of them are still my own. Yet I do not hear my daughter represented by thought leaders in higher education who preach transformation, disruption, and market-based skills. How can I trust that strategic planners who take these ideas for gospel are truly planning the brightest future for today’s children?

The bright side of negative thinking

We evolved to imagine the worst. A truly wild animal is always alert to danger, ears swiveling, nose twitching, muscles flinching at false alarms so that they don’t fail when the threat is real. I am like that sometimes as a parent, involuntarily imagining catastrophes that make my heart race, which I know is meant to help me protect my kids.

Ehrenreich discusses many tragedies that might be attributed to a byproduct of deliberate positive thinking: “the reflexive capacity for dismissing disturbing news.” The 9/11 attacks succeeded, in part, because government officials believed America to be so invulnerable to devastation that they minimized the intelligence that might have prevented disaster. There were warnings about potentially catastrophic flooding in New Orleans at least four years before Hurricane Katrina hit. And the financial meltdown of 2007, dramatized unforgettably in The Big Short, was driven by a conspiracy of denial. This is precisely what makes me distrust the Nido Qubein model of university leadership: it looks for all the world like a bubble.

If negative thinking can sometimes help us survive, it is also an indispensable tool in seeking truth. Socratic dialogues are not liturgies or creeds, chanted in unison. This is why another word for scholarship is “criticism.” Typically one must demonstrate, at the outset of an argument, how a new thesis fills a gap in what has been previously said on the subject; in this way scholars are conditioned to frame their own arguments with the inadequacies of others. In fact, science cannot claim to be science if it is not falsifiable, if there are no empirical measures by which it could be logically disproven.

Churches and universities originally shared this humility in the pursuit of truth. In fact, I once argued that good teaching was more akin to a faith journey than to continuous improvement in business. Most people of faith, I thought, would recoil from a Christian service where the congregation gathered to conduct self-evaluation of one commandment a week, guided by a consultant who was not even a believer, himself, but had been hired by the congregation to hasten its piecemeal progress toward righteousness. If this discussion were extended to the sacred text, the parables attributed to Christ might be excised for lack of clarity. And forget about the Book of Revelation. I wondered how the result of such an approach to faith or teaching could yield anything other than whitewashed sepulchres.

But Ehrenreich shows that pastorpreneurs have been doing this very thing: surveying prospective parishioners and building a church to match their fantasies: “Hard pews were replaced with comfortable theater seats, sermons were interspersed with music, organs were replaced with guitars. And in a remarkable concession to the tastes of the unchurched…the megachurches by and large scuttled all the icons and symbols of conventional churches — crosses, steeples, and images of Jesus.” Why would they do that? To avoid scaring people off. The whole idea was, in the words of Frances Fitzgerald, to “lower the threshold between the church and the secular world.”

I don’t need to belabor the parallels to higher education, where rigor is often seen as another word for racism, where professors lower standards and inflate grades to avoid being penalized on student evaluations or outright fired. Accommodating students as if they were customers might boost retention, but it often hurts students in the long run. College admissions videos typically have more in common with Chamber of Commerce brochures than with intellectual life because students presumably can tell within 30 seconds of setting foot on campus if it’s a good fit. Maybe what today’s third graders are really going to want in their college experience are cute cafés where they can buy coffee and scones or retro video arcades.

There is another possibility: that students like my fifth grader would really prefer substance over shinola. And just as bright-siding in business forces everyone to wear a fake smile, sometimes with disastrous results, so also do university leaders’ visions of disruption pose real danger to people who have devoted their lives to a discipline and to the disciplines themselves. When Ehrenreich was first diagnosed with cancer, she bristled at those who insisted that she see it as a chance to emerge stronger, somehow improved by the experience. Sometimes resilience means taking stock of our injuries, recognizing that even if something didn’t kill us, it has weakened us in ways that will require a long rehabilitation. What we want in times like these is durability, not rapid transformation.

If I were a university president, I would replace the pep talks with this gem from Ehrenreich, which I believe would resonate with many teachers and researchers: “A vigilant realism does not foreclose the pursuit of happiness; in fact, it makes it possible.”

Today’s post was also featured at Inner Life, a collaborative that I launched with Mary L. Tabor, of “Mary Tabor ‘Only Connect’” and Sam Kahn of “Castalia.” Subscriptions to Inner Life are free, and you get two posts a week on intellectual life from a variety of writers. Join us here.

Very interesting issue of your newsletter, thank you.

Funny you should mention Qubein. I work in High Point (in one of the few institutions that DOESN'T have a purple HPU umbrella or flag conspicuously displayed).

His influence is quite substantial and his name is everywhere, as in they just renamed a STREET for him. As HPU takes over more and more square footage in High Point, more gold-tipped fences go up around that square footage. The shopping center across the street from HPU has the side facing the university covered in astroturf, so parents and students don't have to look at, gasp, SHOPPING CENTER CONCRETE WALLS.

Forgive the snark, but HPU is a joke among locals. It's basically a finishing school for rich kids from Up North, (or any rich kids for that matter). Qubein is a fundraising MACHINE and HPU looks like a 5 star resort.

I hope the students are actually learning something other than how to be 'positive'.

Further reading here: https://www.theassemblync.com/education/higher-education/nido-qubein-high-point-university/

I'm going to chime in here as a coach; so, someone who's business it is to prompt professors to search for and explore possibility. At its core, my work is optimistic. And I agree with Ehrenreich and you in your shared diagnosis of universities adopting failed corporate strategy models (I have both experience with and thoughts on strategic planning, for example, and am leading a session for dept heads in a Humanities faculty at a large comprehensive in March). But I would diagnose the illness and possible cure differently. To keep with your religious comparison, I'd take a more Buddhist stance -- where academics (leaders, professors) and their students need to come to the keen awareness that suffering exists, imperfection exists; we will continually fail to hit perfection in any form; humans are flawed. So, it is our duty and obligation to bolster our compassion and connect with one another as human beings. What toxic positivity has none of is empathy. Toxic positivity doesn't SEE people, is not present with them. Leadership that foregrounded emotional intelligence and agility, and above all compassion, would chart a different path.