Friends,

Today I’m sharing a chapter from my memoir that recounts how transformative my discovery of Willa Cather was as a college sophomore. If you are participating in the Friday series and are reading My Ántonia for the first time, be aware that there are some spoilers here.

This chapter is a good reminder of how memoir requires us to reconstruct our past according to how we see it at the time. I wrote the version below during my first sabbatical, just after earning tenure. I’d been married for a year, and my eldest daughter would be born later that spring. In fact, the contract for my book arrived the very day we brought her home from the hospital.

It was a time of plenty. My courses were full, often waitlisted. I believed that my students would find the most fulfillment if they listened to what their passions suggested their futures could be. That’s how it had worked out for me.

I’d have to frame this story differently if I were retelling it now. The financial stakes are so high for today’s college students that there’s little room for error. Self-discovery presumably takes place in Grade 11, or even earlier. No one veers easily from a career path while assuming lifelong debt. The decision I made as a college sophomore was only possible because my education was affordable.

This would be an elegiac tale if I were drafting it afresh, given how much my circumstances have changed since the first telling. But just as I cannot imagine my life without my children, I don’t regret following my heart as an undergraduate. Would playing it safe have necessarily led me to a better place? Some might see my story as Exhibit A in the rationale for slashing humanities programs. But I see it as a reminder of what education can be when it is open to everyone, when freedom is the highest measure of success.

Josh

The Day I Became An English Major

Around the time I flew back to college for my sophomore year, I saw a cartoon that summed up how I felt. It was a tetraptych, four portraits of a young man, with a simple caption: The Four Years of College. In the first he looked much as I did in my high school senior photo, clean cut, serious, collar buttoned over a tie. In the sophomore portrait he had shoulder length hair, a long beard, and hoop earrings, one hand raised in a peace sign. He mellowed somewhat as a junior, hair cropped to his ears but still falling into his face, the beard trimmed to a soul patch and goatee, the earrings now mere studs. And then his senior picture looked exactly like the first.

The cartoon has vanished, but I often thought of it while speaking to first-year students who reminded me of myself at that age, the ones with no doubts about their future plans. Mostly I let them talk and cheered them on. But there were always a few who sat a smidge too straight, who ruffled a little if I asked about a Plan B. Give yourself time, I’d say. You might not know yourself well enough yet to be quite so sure. They were the ones who came back as sophomores and asked: How did you choose your major?

The short answer, I said, is that sometimes you don’t choose your future. Sometimes it chooses you. The long answer took me back to an immigrant girl watering a team of draught horses in Nebraska, her neck dark from the sun and her body lean and firm beneath her clothes.

My advisor, Dr. Snow, was a kindly man with a shock of grey hair and a gentle laugh, the lone Political Science professor at King College. He taught from a rickety lectern with an iron base and a wooden cabinet where he shuffled his coffee stained notes after sketching an outline on the green chalkboard. Beneath the desktop of the cabinet was a small shelf, about waist high, with just enough room for him to prop one knee as he spoke. It was a trick to keep our attention, like the gaps in his outlines that we were to fill as we jotted our notes, a moment we watched for every class, never quite sure when the right leg — always the right — would rise and slowly disappear into the lectern, until he stood before us like a blue heron motionless in a bog. Once a joker asked Dr. Snow where he kept his leg for the entire period. He grinned and said, “In Narnia.”

Dr. Snow oversaw the prelaw program, so I met with him every fall and spring in his office on the third floor of Bristol Hall, a crumbling brick building which also housed the History and English departments. My law school ambitions were cooling fast after a few Political Science classes, where I found I could often rationalize at least two of the answers on the multiple choice exams, almost always talking myself out of the correct one. I knew the questions were meant to prepare me for the Law School Admission Test, but the right answer often hinged on what felt like a petty distinction. No matter how fervently I challenged the questions I’d missed, Dr. Snow always smiled and insisted, politely, that I was wrong. At the start of my sophomore year, I could feel a crisis of confidence building.

Why was I here? Scribbling notes on political action committees and the branches of government wasn’t what I imagined while watching Inherit the Wind as a high school senior. I could see no promontory of truth above the sea and fog, just a mess of fine print and nuances as void of life to me as one of Pluto’s moons. Yet changing majors felt like quitting, so I kept scrawling notes the way I kept suiting up for baseball practice, where the ping of the aluminum bats left my ears ringing with futility.

The men and women in my family knew how to hang tough. Once you found a job, you kept it for forty, fifty years. No whining, no hand wringing about whether you might be happier elsewhere. God provided and you gave thanks and buckled down until God took the decision out of your hands again. Promises were so inviolable in my family that one of my cousins appeared at her fiancé’s funeral, after he’d been crushed by a tree on a logging job a few weeks before their ceremony, in her white wedding dress.

I needed an ironclad reason if I expected my change of heart to make sense to my father and the rest of my family. For most of them, books were for the long winter months when the firewood was split and stacked and snapping in the stove, when the family might gather for a portion of The Hiding Place or The Cross and the Switchblade. My mother ventured further as a young woman, persuading my father to purchase the Encyclopedia Britannica Great Books collection, hoping to educate herself from home. But most of the volumes still glistened in their shrink wrap, gleaming like another life just out of reach every time my mother ran a dust cloth down the shelf.

A giant oak tree shaded my dorm room that year, a corner suite on baseball hall where I’d been assigned a new roommate. Calhoun was a North Carolina boy, a tall, rangy kid with a penchant for clutter and dance parties and purple silk shirts. He kept his laundry in a fetid heap by his desk until he’d exhausted his supply of clean underwear and grew tired of going to class commando. An air of defeat soaked the room. I woke to it every morning in the shadow of the great oak, to the stench of the laundry pile, to Cal curled on his side, knees tucked to his chin. And I carried it with me to Bristol Hall, where I copied more pages of notes to memorize, knowing even if I had the full notebook at my elbow for the next American Government exam, I might still miss the hair’s breadth of reason on which the right answers turned.

It was nearly Halloween when I fell in love with a girl.

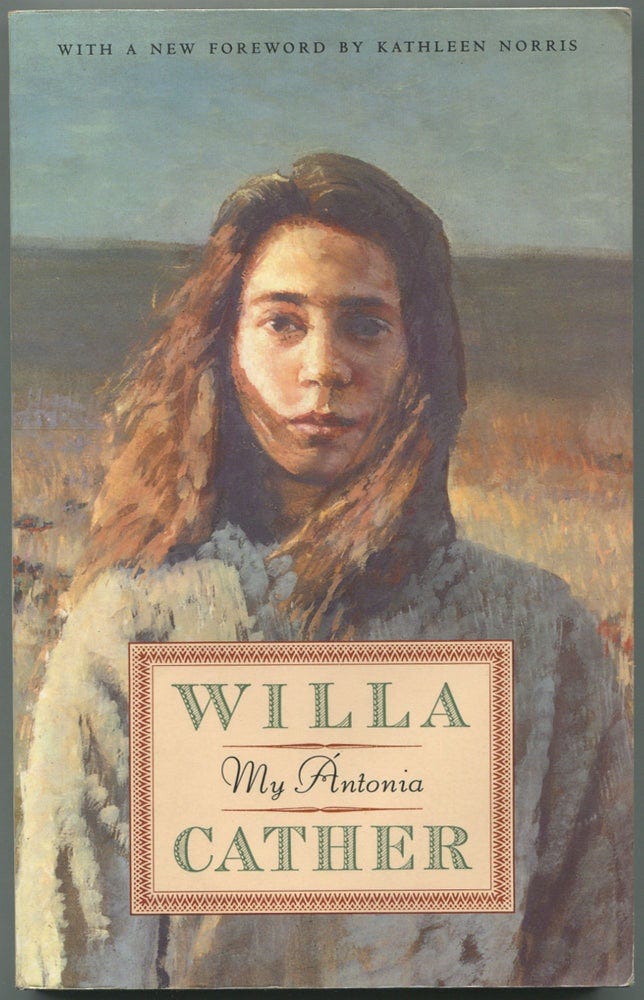

I studied her in my American Literature class, drawn to the hair falling into her face, the glow of her sun-darkened skin, her brown eyes wide and warm and full of light. She gazed at me from the cover of a novel we were reading, My Ántonia, the first book I’d ever read that spoke directly to my own family history. I recognized in Cather’s sketches of immigrants arriving in Nebraska the faces of relatives I’d met during a family reunion at the Czech Days festival in Wilber, where my great-aunt Marcella told stories about my grandfather creeping between rows of onions on their farm during games of hide-and-seek. He was always the easiest to find, she said, because she could see the green onion tops waving as he pulled them to his mouth, munching the juicy shoots as he lay in the dirt.

I knew how Jim Burden felt when he described the raw change of seasons in the country: “There was only — spring itself; the throb of it, the light restlessness, the vital essence of it everywhere: in the sky, in the swift clouds, in the pale sunshine, and in the warm, high wind — rising suddenly, sinking suddenly, impulsive and playful like a big puppy that pawed you and then lay down to be petted.”

Against all this was Ántonia, the pretty peasant girl who coaxed a tiny cricket to sing in her cupped hands, who tried to cheer her father when the frontier broke his will, who gave up schooling to plow the cornfields with her brother and the farmhands. Even as a hired girl in town, Ántonia breathed with the vigor of the wild land, waltzing to the piano players who traveled through Black Hawk, sometimes inventing dances of her own as her feet beat the worn floorboards, her legs lithe and strong beneath her spinning dress.

Cather brought me back to the summer mornings when my mother read to my sister and me on a quilt in the backyard beneath our plum tree, back to the afternoons I stole for myself in my bedroom, lying on the cold cement floor with All Things Wise and Wonderful as blissfully as Jim and Ántonia lay in the prairie grass with nothing but the blue sky and a golden tree to gaze upon.