The following is a new chapter from a memoir in progress, which I aim to finish by the end of this year. The book is an attempt to explain my experience of fatherhood to myself. While I’ve polished the following essay to some extent, it remains very much a draft.

These monthly installments are only available to full members. For access, please consider upgrading your subscription. 5% of my earnings for Q1 went to to Out of the Cold Centre County, a low-barrier shelter and resource center in my local community. In Q2, the same amount will go to Centre Volunteers in Medicine, a free clinic for those with no health insurance and annual income under $38K (individual) or $78K (family of four).

The Gratitude Gap

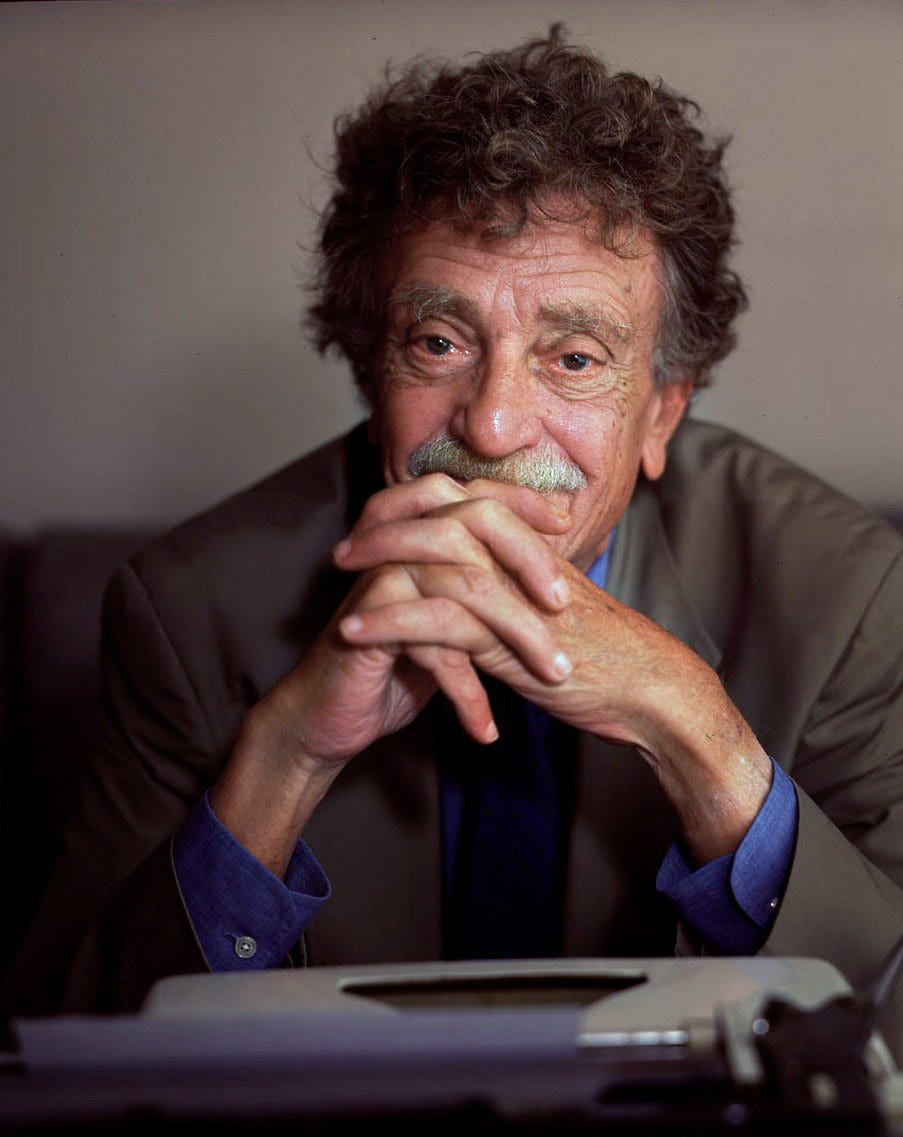

Kurt Vonnegut often repeated a story about his Uncle Alex, a well-read insurance salesman (and Harvard grad) who had little patience for people who were so busy complaining that they forgot to notice when they were happy:

So when we were drinking lemonade under an apple tree in the summer, say, and talking lazily about this and that, almost buzzing like honeybees, Uncle Alex would suddenly interrupt the agreeable blather to exclaim, “If this isn't nice, I don't know what is.”

The funny thing is that even though Vonnegut tried to follow his uncle’s advice, echoing that grateful refrain whenever it occurred to him, he never wrote a book built on that principle.

This is because storytelling thrives on conflict. Without an inciting incident or problem to resolve, a novel or memoir has no stakes, no urgent reason for a reader to keep turning the pages. We imagine that we must be problem posers to write anything worth reading at all, like TV writers who begin every episode with an unsolved crime.

No subgenre illustrates this challenge more than the parenting memoir, which seems to have two lanes: dad jokes and mom rage. Since I didn’t want to write a book like Jim Gaffigan’s Dad Is Fat and couldn’t find many literary memoirs about fatherhood by men other than Brian Gresko’s anthology When I First Held You, that left me trying to find the counterpoint to Rachel Cusk’s A Life’s Work or Lyz Lenz’s This American Ex-Wife, which are more sophisticated versions of Chappell Roan’s comment in a podcast interview that everyone with kids is miserable.

In that telling, parenting is a problem and men are a big part of it, whether they are earning too much or too little, doing too few household chores or in the wrong way, absenting themselves or applying outdated methods. The grievance is the story. So men must either turn themselves into buffoons, the way Gaffigan does, or insinuate themselves into the complaint against toxic masculinity, showing how it harmed them and how they are doing the work to undo it. Self-reflection is always worthwhile, but the goalposts keep moving for fathers, and the conversation often leads back to the only logical conclusion: Mea culpa, mea maxima culpa. If, as Jill Filipovic recently claimed, it’s not a gender equity gap but a gender competence gap, or if women who decide to marry are increasingly marrying down, then no wonder young men are increasingly turning conservative.

Consider these opening lines to Cassie Mannes Murray’s essay “Throwing Pennies,” in which her son is already a potential criminal before he’s even born.

When the ultrasound technician adjusted the wand and said, “oop, it’s a boy” my first thought, the first thing I said to my partner in the deliberately shadowed room was, “how do we raise a non-toxic white boy in the South?” It was my immediate and most primary concern. It was a response that infused my world view; the list of horrors that came to mind of what this unborn boy could be became a red ticker tape scroll below a newscaster. I imagined him already a teenager, shallow and sunken purple pockets below his eyes in a mugshot, for what, it didn’t matter, but the eyes themselves—empty.

This is precisely the kind of problem posing that drives online traffic, sells books, and produces what some call “rage bait” on social media forums. It’s the kind of rhetorical move I taught students to make in their academic essays. Instead of neutrally stating facts, as they preferred to do, I’d urge them to clarify the gap in the research they were trying to fill, the new insights they were contributing to the scholarly conversation. As one of my mentors often said, good writing needs something to push against.

There is indeed a lot to push against in parenting literature, and I’ve finessed my way through complaint-driven narratives with the best of them. One of those essays, “Fathers and Sons,” helped me break into The Missouri Review, one of the most selective literary journals in the country. And I thought that was the ticket to writing a book that might sell.

If you’ve followed this series for long, you’ve heard how that formula was supposed to work as a book: all the ways that my childhood conditioned me to fear and avoid fatherhood, how the births of my children transformed that uncertainty into an unshakable love, how the usual domestic complaints eventually broke my marriage, and how I finally discovered peace and confidence as a single father. I told myself that telling this story would empower other dads, that I’d be doing more than airing my own grievances. Yet I couldn’t escape the fact that a problem-driven story about fatherhood centered myself in what should be a family story. Parenting is hard, being a father is sometimes exhausting, and both my wisdom and ignorance as a parent have deep roots in my past. But the more I’ve struggled to force a story about fatherhood with me at the core, the more dishonest it’s felt and the less interested I’ve grown in settling the score with ax-grinding moms or undertaking a quixotic bid at redemption, no matter how cleverly veiled it might be in literary craft.

A friend once quipped that he thought he was wrong once, but he was mistaken. In this case, I thought I was certain, but I was wrong. I’ve come to see that what was missing was a gratitude gap: in myself and in the discourse surrounding parenting.

Over the past month or two, a question has been nibbling away at my thoughts: What if I abandoned everything I know about memoir writing and began not with the problems, but with the blessings of fatherhood? What if I thought of my life with my kids less as a narrative arc propelled by escalating tension and more as a song with a root chord of gratitude, memories for verses, and an affirming refrain? How could I translate Uncle Alex’s principle into vignettes about happiness that still had all the high stakes we expect from good writing?

No way to know but to try.