The real reason Americans are angry about college debt forgiveness

The soul of America is anti-education

A few weeks ago the Biden administration unveiled its student loan forgiveness program, and you probably have a clear opinion of it. Either you think that helping people who are struggling with college debt is a good thing, regardless of how you financed your own college education, or you think that you are being asked to bail other people out of debts they assumed of their own free will.

But as is often the case, that’s not really what people disagree about. I recently saw this ad while watching college football, and while it initially shocked me, I think it’s closer to the heart of the debate about higher education in America than any of the talking points about budgets.

This propaganda nugget was produced by the American Action Network, which claims to promote “center-right policies based on the principles of freedom, limited government, American exceptionalism, and strong national security.” There are reasonable arguments to be made from that platform. William J. Bennett made one of them in his 1987 op-ed “Our Greedy Colleges,” where he argued that increases in federal financial aid only encourage increases in tuition and other student fees. Research shows that the Bennett Hypothesis has only accurately predicted the behavior of for-profit institutions. Still, a lot people (including me) continue to wonder whether it is good policy to pay down student debt without addressing the root causes of rising tuition.

But the American Action Network is not making a reasonable argument. You can hear it in the sneering tone and see it in the actors’ smirking faces. The punch line, “College is on me,” is dishonest and the producers know it. Who thinks that $10K in debt forgiveness goes anywhere near covering the full cost of anyone’s education these days? What you get from the ad is an honest expression of American anti-intellectualism. People used to be too polite to say these things out loud, but you heard it twice in 60 seconds: it’s those struggling artists and theater majors that working people really don’t want their money going to support.

I’ve been haunted by this ad for two reasons. First, it expresses a disdain for learning that is as old as European settlement in North America. It is alarming to hear that loathing expressed so unabashedly, almost like a racial slur. But even more than this, I’m troubled by the incoherence of the message. When you peel back the sarcasm, it is very difficult to say what the ad is for. Outrage in search of purpose is a deadly thing.

Storytellers and fiddlers

None of the characters in the ad claim to be Christian, but their suspicion of art and literature can be traced directly to Puritan New England. Nathaniel Hawthorne captured the sentiment in his introduction to The Scarlet Letter, where his narrator imagines what his Puritan ancestors would think of him becoming a writer.

No aim, that I have ever cherished, would they recognise as laudable; no success of mine — if my life, beyond its domestic scope, had ever been brightened by success — would they deem otherwise than worthless, if not positively disgraceful. “What is he?” murmurs one gray shadow of my forefathers to the other. “A writer of story-books! What kind of business in life, — what mode of glorifying God, or being serviceable to mankind in his day and generation, — may that be? Why, the degenerate fellow might as well have been a fiddler!”

Anyone still trying to teach the arts and humanities in high school or college will recognize these words — worthless, disgraceful, degenerate — as descriptions of how their work is often perceived by the general public. It’s the sentiment that justifies book banning. And, ironically, it is the same contempt and narrow definition of what is serviceable to mankind that allows the corporate university to keep whittling away at the liberal arts.

I recently heard from a former student that House of Light, a book of poems by Mary Oliver that we read for a course in environmental literature, helped him get through a divorce. While working through his grief, he took Oliver’s book with him on hikes where the land and Oliver’s particular way of seeing it helped him feel hopeful again. If that isn’t serviceable to humanity, please explain what is.

But even Democrats often speak as if they don’t know their history. President Biden is fond of claiming that we’re in a battle for the “soul of the nation.” Haven’t we always been? When I hear rhetoric like that, I think of the year 1628. The Pilgrims had only been established at Plymouth for about eight years. There was no nation yet, just a smattering of colonies, and not far from Plymouth was a competing colony called Merrymount. Its leader, Thomas Morton, had convinced several servants to desert their masters, and they lived together in an egalitarian collective that supported itself by trading guns, ammunition, and whiskey with neighboring Native communities.

William Bradford, Governor of Plymouth, felt that Morton was endangering the Pilgrims by arming people they wished to subdue, but he also thought Morton attracted lowlifes. Bradford even referred to Morton’s band as the “scum of the countrie.” When Morton constructed an enormous maypole to honor the Anglican saints Philip and James, the Pilgrims mistook the revelry for idolatry. It did not help that the Maypole dancers cavorted with Indian women or that they had written a poem for the occasion riddled with mythological allusions. The Pilgrims cut down the maypole, imprisoned Morton, and sent him back to England, which is how one was canceled in those days, if not by hanging, beheading, or burning at the stake.

Bradford believed that Morton was an atheist who wanted to revive pagan traditions, such as bacchanalian orgies. For his part, Morton scorned “the precise Separatists” for being too uneducated to understand the symbolism of his festival. Morton was, in fact, blending a traditional Anglican ceremony with the Roman celebration of Maia, goddess of spring, for whom the month of May is named. The point of Morton’s maypole was to have fun, let off steam, and raise the morale of young bachelors who found their lives in the New World lonely and bleak.

Morton thought that learning, even just for the fun of it, allows us “to converse with elements of a higher nature than is to be found within the habitation of the Mole.” But to the Pilgrims, poetic allusions to Maia, Oedipus, Triton, Proteus, and other mythological figures represented “unnecessary learning.” Which view lies closer to the soul of America?

I worry about this for my children, because I don’t think it’s really a question of college affordability that we’re debating. It’s the Puritan grandfather versus Nathaniel Hawthorne, William Bradford versus Thomas Morton. The real fear for conservatives is that more students might choose to study art and theater if they really had the freedom to do so without enormous financial risk. Anyone who learns enough about history to perform as a Shakespeare character is going to be difficult to manipulate politically and is going to favor a more inclusive society. If the stage can be framed, like the maypole, as the playground of degenerates or as a frivolous pastime for rich people who pay for it on their own dime, it can be effectively written out of the soul of the nation.

Anger in search of purpose

The characters in the AAN ad imagine that their hard-earned money is being wasted on rich kids who are trifling with art and theater. I can understand that resentment, as factually incorrect as it is, but what troubles me more is that none of these characters seems happy. One says he spends more time working on cars than with his own family, another claims to be breaking his back mowing lawns, and the third is working two jobs where, by her own admission, she guzzles coffee to keep her strength up. If they had formerly been employed in lucrative manufacturing jobs that had been replaced by automation, these characters would be more comprehensible. I can’t quite tell if they represent people who never had other opportunities or people who truly believe that they made their own beds and ought to lie in them.

How do you read these characters? Let me know in the comments.

American suspicion of education, as George Packer explains, is rooted in a belief that “the authentic heart of democracy beats hardest in common people who work with their hands.” But the characters in this ad are not proud farmers or loggers or entrepreneurs. They seem to feel stuck in dead-end work that no one appreciates, and the only virtue they associate with their labor is the right to keep every penny to themselves. If these characters were real people, an affordable college education would be the best way for their kids to avoid a similar fate. But they seem driven by a kind of spite: I got left behind, and you shouldn’t get a chance if I didn’t.

It is no coincidence that all of these actors are white. Much ink has been spilled noting the disturbing similarities between Donald Trump’s support of white supremacists and Adolph Hitler’s transformation of economic resentment into ethnic nationalism. The AAN advertisement captures a simmering economic resentment in America that, as yet, remains too incoherent to support real mobilization. The January 6 riot similarly remains a mystery to most political experts, who recognize that the rioters expressed rancor without any clear purpose or plan.

Anger like that typically finds a target if it doesn’t have a clear one at the outset. In Puritan New England, it was independent women, Quakers, slaves, and those who dared criticize the religious courts. If Thomas Morton had still been around in 1692, he would assuredly have been hanged as a witch. In twentieth-century Germany, the primary targets for working-class anger were Jews, but the list of victims grew to include anyone the Nazis viewed with scorn: people with disabilities, queer people, and dissidents of all kinds. Contempt as obvious as that in the screenshots below is often a precursor to violence.

You can’t trust everything you see on television, but when I see identifiable propaganda aired during a midday football game, I consider it a cultural moment worth noting. The analogy is still distant enough that I can’t equate the American Action Network with Nazi propoganda films about concentration camps like Terezín. Plenty of alt-right media sources serve up far worse than the AAN ad on a daily basis. But when I see this next to the usual ads for car insurance and hoagies, alarm bells begin to ring.

I’m also haunted by the similarity of the ad in tone and substance to much of what I heard growing up in rural Montana in the 1980s and 90s. Up until the very end of my senior year of high school, I had resolved to forego college — not because the cost was prohibitive, but because I was afraid of being indoctrinated by liberal college professors.

One urban legend I heard has been around since the 1920s. Maybe you know the one about the atheist professor who held up an egg in class one day (or a piece of chalk in some versions), announced that he was going to drop it, and challenged God to show that he was omnipotent by suspending the law of gravity that would otherwise smash the egg on the ground. The professor was humiliated when he dropped the egg and it caught his shirt sleeve, rolling unharmed down his leg, over his shoe, and across the floor. I thought college would be something like that: a perpetual showdown between me and godless academics.

When I finally decided to go to college, I chose a Christian school in Tennessee. My beliefs were challenged there, but not by intimidation or force. Instead I learned to recognize the weakness of confirmation bias and ad hominem arguments, to weigh context and evidence carefully, and above all to be humble about the conclusions I drew. Just as the results of a scientific experiment are never final, but remain perpetually open to falsification, so I learned to regard my opinions as works in progress, not as objective truths. Whereas I’d been raised to stick to my principles no matter what, college taught me that changing my mind based on new information could be a better measure of character. And that’s where I learned about Nathaniel Hawthorne and Thomas Morton.

The people at the American Action Network are like William Bradford. They don’t want anyone getting the kind of education I did, even if they pay for it themselves. The fact that I did not pay for my education entirely, but benefited from a combination of Pell Grants and Stafford Loans that, combined with competitive scholarships and a good summer job, helped me avoid crushing college debt before it would need to be forgiven would not mollify anyone presently opposing Biden’s plan. I prefer Thomas Morton’s notion that learning ought to be for everyone, and that it should lift us out of our individual lives into a celebration of the human history that we all share, such as the story of how the month of May got her pagan name.

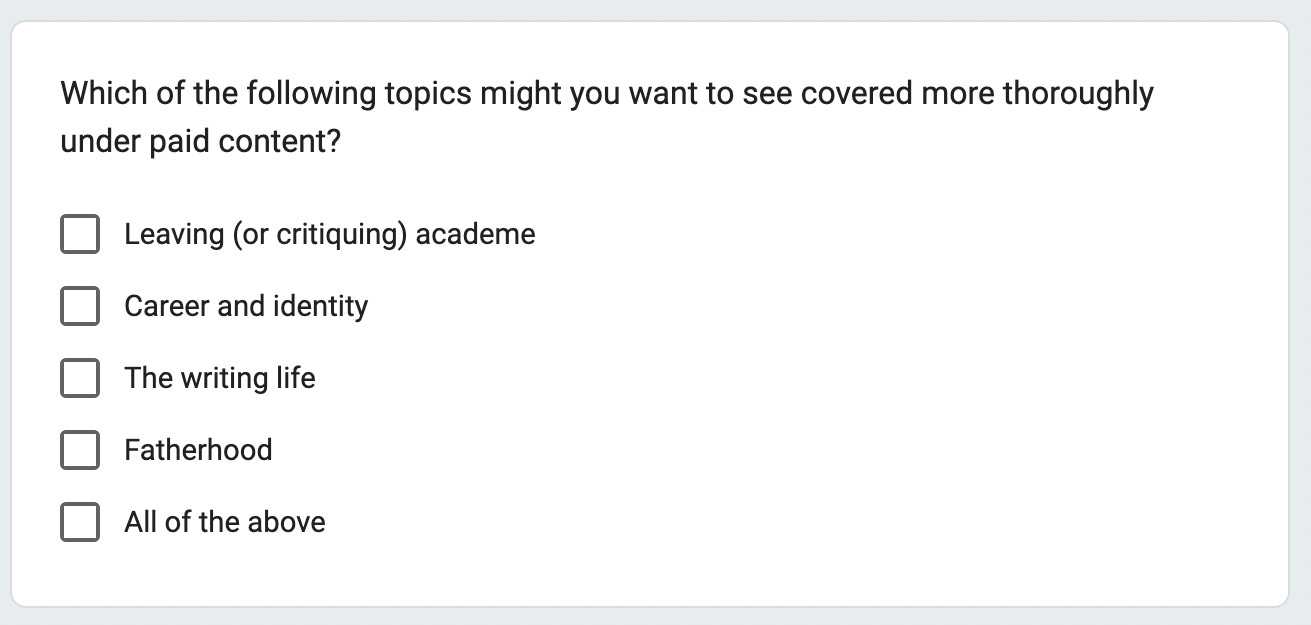

Thanks to your support, I am now approaching the point at which it might make sense to add paid content to The Recovering Academic. Over the next few months, as I plan the future of this series, I’d be grateful for your feedback on topics that you’d like to see covered more deeply or new features that you’d like to see added. If you’d like to make suggestions, please complete this Google Form. Or you can always send me a note at dolezaljosh@gmail.com.

I grew up with those people, and dropped out of college to go back to their lifestyle, which in my youth felt so tight knit and understandable. Conservatives have lost, scarily understandably , their sense of hope for the future... so many psychological identity anchors are getting nuked... as their financial independence circles the drain. A progressive mindset is fundamentally more at ease with a changing society... I think on a primal level ... one looks to the past and the other looks to the future.... and for many they no longer see their place .... and we hate deep down being useless or not wanted .... I think it’s that existential angst about a role in society and connection that is the real zeitgeist of the ad.... even more deeply troubling because although the ad is cheap political propaganda.... the existential issues are profound and instead of coming together to figure out how we’re gonna get through another industrial revolution - this one even scarier than the last in many ways - all we have is demonization and hatred of each other at the top. Empathy compassion unity if you’re out there please come to planet earth

The humanities help us understand the human condition. We could all use more education in the humanities. ✅