Most of my content in 2025 is free, but I appreciate the support of readers who make my interviews possible. Upgrading your subscription unlocks my monthly essays from a memoir-in-progress, as well as the entire archive. I’m also proud to be a Give Back Stack. 5% of my earnings in Q3 will go to the State College Food Bank.

See my accountability page, with receipts for Q1 and Q2, here.

The Things Not Named — With River Selby

Joshua Doležal: Welcome back to The Things Not Named. I’m Joshua Doležal. This year I’ve been asking writers how they know high-quality writing when they see it and how their own sensibilities have been forged. My guest today is

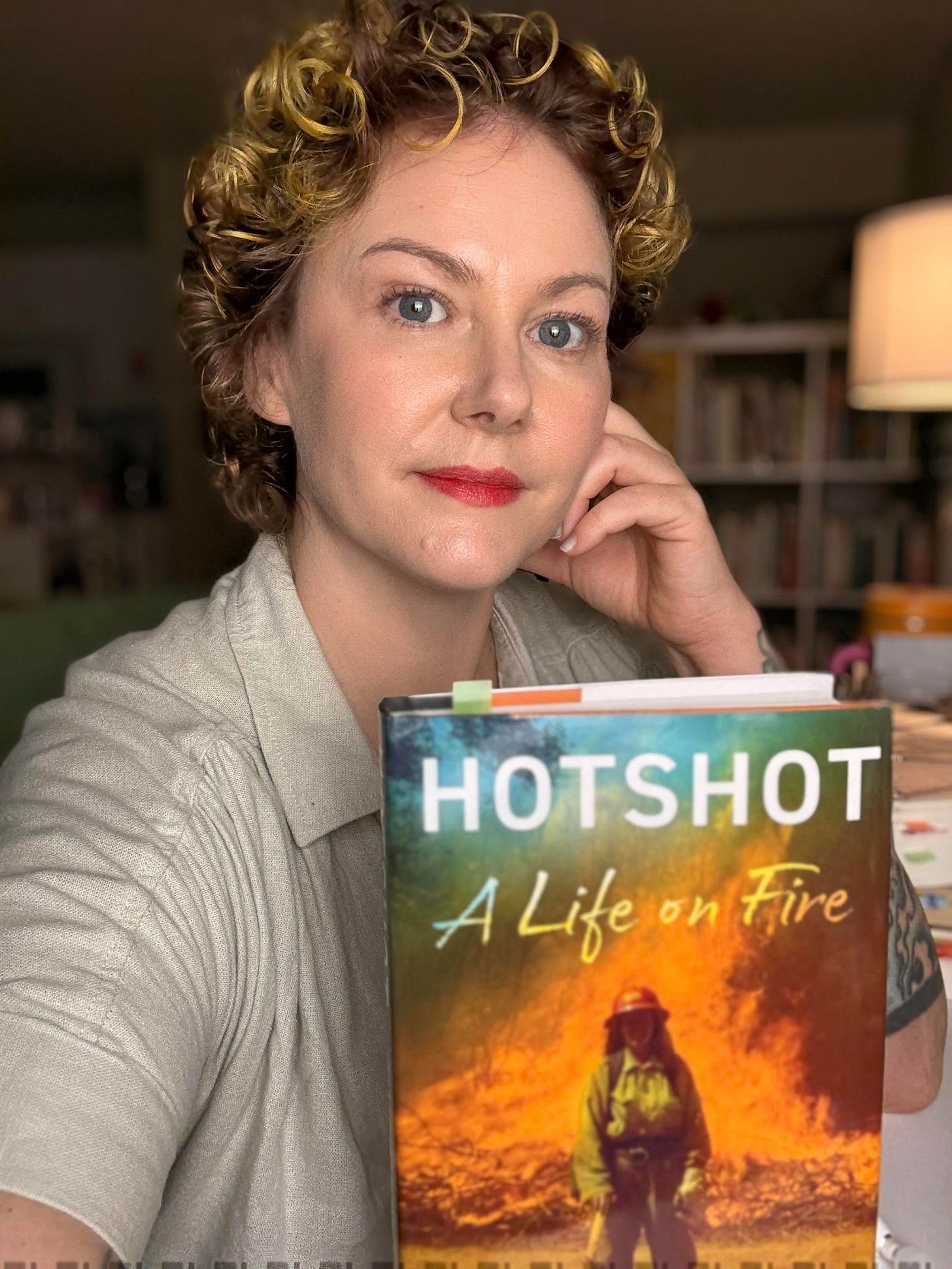

.River is the author of Hotshot: A Life on Fire, their first book. River worked as a wildland firefighter for seven years, stationed out of California, Oregon, Colorado, and Alaska.

They are currently a Kingsbury and Legacy Fellow at Florida State University, where they are pursuing their PhD in Nonfiction with an emphasis in postcolonial histories, North American colonization, and postmodern literature and culture. River has spent nearly a decade researching the history of fire suppression in the United States, Indigenous fire and land-tending practices, climate change impacts, and ecological adaptations across North American landscapes. River holds an MFA in fiction from Syracuse University and a BA in English and Textual Studies from the same institution, where they served as a Remembrance Scholar.

Visit their website at www.riverselby.com and find them on Instagram @riverselby.

As you might know, I was a wildland firefighter for many years, so I was delighted to see this new release. I hope you enjoy our conversation.

Joshua Doležal: It sounds like you grew up reading a lot and you describe in your book about firefighting a kind of journaling habit that you were chronicling your life as it was happening more or less. But it doesn't sound like you started writing seriously until near the end of your firefighting career. So when you look back to some of those early influences, before you even started consciously trying to write what were you reading? Or what were some of those early guideposts for craft, when you responded to literature powerfully and you knew that what you're reading was high quality?

River Selby: I had an unusual upbringing. I was born into Scientology. My mom left when I was two and she was very into new age things, and she read a lot. She had dropped out of high school. But she was very smart and her bookshelf was filled with new age books of the eighties persuasion and also a lot of true crime.

And then some Pearl S. Buck and Rachel Carson and Aldo Leopold, who she got from my grandmother, who I also lived with for a while when I was younger. My grandmother had left her wealthy family in Texas to marry my grandpa, who was a Marine. In World War II she was a nurse and they met during the war.

And my grandma's bookshelf was also filled with true crime and all kinds of pulp, fiction and nonfiction, but also all of the Shakespeare and Emily Dickinson. She loved poetry, loved renaissance poetry. Read to me a lot, encouraged me to read beyond my grade.

I talked really early. I read really early. I was very verbal when I was a child. And too verbal according to many of my teachers. And we also moved a lot. And so reading was my way of connecting with the world because I didn't connect with my peers very well. I was also autistic and didn't get diagnosed until a few years ago.

And so I kind of read all of the stuff they give to kids like Laura Ingalls Wilder. But I also would go to the library and go to the bookstore. I started out reading beyond my age with Stephen King, Dean Koontz, stuff like that because I really loved the genre of fiction and horror. And then started reading more nature writing. When I was a teenager, I read Mary Karr’s, The Liars’ Club and really became a fan of memoir because it was a way that I could imagine myself out of my life in a way, because memoirs are almost always writing from a place in the future narratively.

Joshua Doležal: When you started to think about writing your own memoir, I was curious about who some of your influences were, but it sounds like you discovered the literary memoir pretty early. So there was kind of a period there where it was very much a scene that was emerging as you were a teenager. What spoke to you about Mary Carr's book and how she made literature out of her life?

River Selby: It's interesting for me to reflect back on my reading life when I was a teenager because I ran away for the first time when I was 12 and was homeless on and off throughout my teens. Sometimes I was encountering books and sometimes I just wasn't because I wasn't living in a home. And I think that when I was encountering books, they were almost like, I almost just picture someone climbing up a cliff and they were the handholds for me. And Mary Karr’s The Liars’ Club. Yeah, my childhood was really unstable and my mom had mental health issues and was an alcoholic and she had this kind of cycle of boyfriends coming through who also were not very stable and then married an alcoholic when I was 13. And so her book felt like being seen because so much of what I had read felt very constructed and far away from me, whether it was fiction or nonfiction. But because of her voice in that book she really inhabits her younger self.

And I think that because that voice was so strong and there wasn't really a narrator that was placed outside of the time of the book, that made me feel like I had a companion almost in my own experiences, so it was really special to me. And I don't think at that time I was thinking, I want to be a writer. That thought was so far away, but I do think that subconsciously it was planting a seed of, oh, well this person lived this life and now she has this book and she's a writer, and so maybe that's a path that I could take.

Joshua Doležal: For a lot of years, I'd associated memoir with autobiography. Ben Franklin's autobiography is very chronological. There's not a lot of layering that happens with it…sort of this happened and that happened.

But literary memoir, as I understand it has more fictional elements to it. And also some layering of what we call the voice of innocence and the voice of experience. The younger self immersed in moments that that self can't see or understand, blinded by impulse or just naivete and the voice of experience that can make meaning of it or see a bigger picture—read against the grain of some of what the younger self saw.

So I liked the texture of that and it really fit my own life story because I'd grown up in an evangelical home and I'd left that faith tradition. So there was a lot of before and after distance for me to use. And I think that's true for you as well, because in your memoir, Hotshot, you use she because your name was Anna then. And so you've since rediscovered or evolved in your identity. The voice of experience is quite different, in a very literal sense, from the voice of innocence in that book. Is that fair to say?

River Selby: I needed to have a certain level of authority narratively embedded into the prose. That was a huge process personally, psychologically, because so much of memoir for me, and I think for some others as well, in that reflection for me, I had to go back and re-experience those things and essentially not re-traumatize myself, but I had to be in that space and it was not a comfortable space.

I would write from that space, and my authority wouldn't be there yet because it was so still in the past. And so part of the revision process was having to work through so many things personally and kind of parse through things so that I could write about my past self in a way that was not judgmental, that was not scared.

That was where I could really bring myself forward in all of my flaws, while also bringing forward a lot of the cultural issues I was trying to engage with. And also pulling out things. As far as my non-binary identity, I look back at myself then and I see myself trying to inhabit an identity that didn't fit me.

Joshua Doležal: So last week I pulled out one tool from your book because I really admired how you'd used it. And it was signposting, which I really first understood in radio form, where you would get a teaser clip and then it's almost flipped from academic writing.

In academic writing, you always identify the speaker ahead of time. I spent a lot of time working with students on signal phrases and seamless integration of quotations and things like that. And in radio it's completely the opposite. You want to let an audio artifact build suspense or intrigue and then identify it almost immediately after.

So it’s an intuitive thing where you anticipate a point of need for the listener, and then address it at that point of need. In your book, I thought it was especially evident because firefighting is such a subculture with its own arcane language. And that's a real barrier for readers coming into firefighting, not knowing what a trunkline is or what a Mark 3 pump is, those kinds of things.

You could have done it very tediously. But instead you just told the story in an immersive way. You set the scene and then would name the thing. Piss pump, for instance, was one of the examples I used. And in the very next sentence, you would then describe either the tool or you would just show how it was used or you would address what surely was confusion for the uninitiated reader. And I don't know how conscious you were of that, if that came through the editing process as you're working with your commercial publisher or if that was something that you learned along the way in your coursework.

River Selby: So thank you. I really appreciate that because like I said, I teach writing, but usually when I teach it, we are looking at something and taking it apart. And it's also an intuitive process, so I'm seeing what my students are seeing and then I'm helping them draw things out. So for me, it's very helpful when someone like you is able to say, oh, here's something you're doing. Tell me how you did that.

It was partially the editorial process and partially it was a mix. I mean, of course when you come from any sort of community that has its own jargon, like wildland firefighting is mystifying. It's a whole world. And also before I wrote my book, I read every single wildland fire memoir that existed and also was reading a ton about just the history and everything.

And so I saw how other people had done it that maybe worked or wasn't working for me. And I think that first of all, when my editor would flag things and say, what is this? What does that mean? What's that? It would've been very easy for me to just put things in parentheses or define things in the moment.

But because of my fiction training, that's not how I want to do things. I want to create an immersive experience for my reader. Sometimes it would take me a while to figure out like, how do I explain gridding to a reader? And then, it occurred to me that you don't only do gridding in fighting wildfires, you also do gridding if there's a search and rescue or something. And so that's the example I used so that a reader could understand what that looks like. And so I would think about ways that I could put it into context for a general reader, things that the general public would know, how to bring the reader into a moment so they can see it in action and how it's working.

I think depending on the person's exposure to fire there can be more than a moment of confusion and I'm okay with that. I'd rather have them have like a little moment of not knowing than to take them out of the text with an omniscient voice coming in to explain something in a way that doesn't fit into the text.

Joshua Doležal: I have a related question because this is something that every memoirist deals with: how to write ethically about others.

So there are some pretty clear-cut moments where there are some jerks on your crew and it's pretty obvious why certain characters would be portrayed as they are, and I assume authentically and accurately. So there are other more private moments that involve relationships where there are particular details about other people. And so I wonder how you navigated that. How did you make some of those choices, especially with people that you'd had brief or longer-term relationships with?

River Selby: Can you give me maybe one example?

Joshua Doležal: Well, I think Colin is someone that you had a longer-term relationship with. There's some other guy, I'm forgetting his name. There were some details about his teeth chattering during intimate moments and things. So I'm wondering how you made those choices.

River Selby: So basically all identifying details are changed of people like that. Of the people I worked with, there is certain background information has been changed a little bit. Physical appearance changed, stuff like that. And that was protective for sure.

And also, as far as the relationships I was in, like Colin and Lewis, those aren't their real names obviously. But there's a lot that I didn't share and there's a lot that I didn't say about those relationships. And I think that really what I was writing about was my experience of them. And I also think that this is one of the reasons that at the beginning of the book and in the introduction I was like, memory is a tricky thing. These are my recollections. I have journals, I have conversations I've had with people. I have my memories, but also memory changes. Each time we remember something, it changes and it's fallible. And so I am one of those writers that I don't really, other than changing details to protect people, I'm not one to add things for story. I don't do that with nonfiction. And so I just wanted to be honest about my experiences and I think that anyone reading a memoir who is not in their twenties anymore, knows what it's like to be in your twenties.

I also really wanted to write about the kinds of dynamics that create some of the behaviors I see from crew members in the book in a way that doesn't excuse them for those behaviors. But that explains why those behaviors are accepted. Why they're even encouraged sometimes. I'm talking about sexual harassment, gender stuff, and firefighting. Why it's a systemic issue, not an individual issue. That's one thing that I really wanted to engage with craft-wise too, so that the reader would see it from a zoomed-back place and not say, this person is the problem. It's this system is a problem. Even with my superintendent of the first crew, he's not the only person behaving in that way. It's a system.

Joshua Doležal: I don't know if you'd agree with this, but when I was working with students trying to navigate the ethics of writing about others, one of the pillars to me is that whatever scrutiny others are subjected to, I have to subject myself to. And so in those moments with Lewis, it's not just his lack of availability or his particular quirks with lovemaking or whatever that's the focus.

It's also what you seem to recognize as maybe unhealthy impulses in yourself, almost irrational desires that after one or two encounters, you had this urge to just marry him. And revealing those kinds of things to show imperfection both ways, I think, is one of those pillars of writing about others. We don't just point the finger or subject others to scrutiny or embarrassment if we're not willing to put ourselves under the same microscope.

So I felt like in those segments it was even-handed. Even with some of the power dynamics on the crew, the ways that you had been perhaps conditioned to acquiesce to the systemic forces or moments when you were disappointed in yourself for not being stronger or more forceful or proactive, that was all part of the picture, I thought, rather than just as you're saying, vilifying an individual or presenting a kind of hopeless picture of the…you're trying to expose all layers of it, not merely, say, the perpetrator's role. Is that fair?

River Selby: Absolutely. I think, and there was no maybe about it. I mean, anyone who grows up in a traumatic abusive environment, anyone who's been sexually assaulted more than once is going to come into experiences with a lot of baggage. And I hadn't yet been in therapy. And yes, that was really important to me.

And it was also one of the hardest things about writing the book — I had to go through those experiences again mentally. Psychologically. Actually, I have chronic post-traumatic stress disorder. And so what happened is that I went into emotional flashbacks, and I didn't know what those were at the time.

And it lasted for a long time while I was revising. And then my therapist finally figured out what was happening and was like, do you know what emotional flashbacks are? And so I had to go through that. And I think that in those first drafts, it's easy to see on the page that I am protecting myself from the reader's judgment. And that's an instinct I think all writers have when you're writing about yourself is being fearful of what the reader's going to think of you, how they're going to judge you. Because often, I'll speak for myself, because I was judging myself and seeing myself on the page as I would think the reader would see me.

I think that in order to expose the truth of any situation, truth is a subjective thing when it comes to our personal experiences, like how we're interpreting things. And so I had to show the reader how I was interpreting things and how I was rationalizing things without trying to justify my behavior or explain away my behavior or make excuses for my behavior.

That it is a very complicated thing to do, but I definitely put a lot of thought into how I wrote about other people and what I wrote about other people and making sure that they're protected as individuals.

Also, a lot of this happened a long time ago. But I do think that's why I felt, especially in the last drafts, very comfortable just laying it all out there because I was like, this is about something bigger than myself. It's about something bigger than individuals.

It's about trauma. It's about the psychology of human beings and systems. And so I don't think I could have done that if I hadn't done my own psychological work through therapy and really shown up in that way. And that was the most challenging thing about writing the book was clearly looking at myself, being honest about myself and my own many shortcomings.

And how it was all part of the way the machine worked—the machine of the experiences, you know?

Joshua Doležal: You wrote this book over six years. It took a lot of years of lived experience before you even got around to writing the book.

But then over that period of time, you were able to get the Holy Grail for a writing career. You got an agent and you got a commercial book deal that came with a $50,000 advance that was paid in installments, but no one would really expect to live on $50,000 for six years. Even for one year that would be seen as low.

And you're doing this while you're studying for PhD on poverty wages. So I guess I have a kind of crass question: is it worth it? Has it been worth it for you?

River Selby: There are a couple different ways that I can think about that. And one is on a personal level, another is on what I'm contributing to the world. And I think that if this had just been a memoir, first of all, it would've been easier to write. But second of all, I'd probably say no if it were just a memoir.

I sold the book, $50,000 advance. I was paid $20,000, which was the most money I'd ever had in one time in my entire life. Like by far, like way far.

I didn't inherit money from my mom when she passed. My dad died without any money. I do not have a safety net as a person. And I had a lot of ideas about things when I got my advance. I also didn't realize that an advance is a loan. I won't make any money from this book directly unless I earn out my advance.

And that's okay with me. I have accepted that reality. It wouldn't have been okay with me a year ago. I would've lost my mind. But I chose to start a PhD program. Had I known what that would look like, I might have chosen differently. That's not a reflection on the program that I'm in. It's a reflection on the way that graduate students are treated and paid across the board pretty much. I think an advantage that I see myself as having is that I’m very adaptable. My level of what feels comfortable financially is much lower than some people's. And I think that in a way, my work right now as a person is seeing my own potential for how I can not be in poverty anymore. What I have to offer, what's the worth of what I have to offer, how can I frame that in a way that feels authentic to other people and feels authentic to me?

Joshua Doležal: We're at a real inflection point with the defunding of higher ed at the federal level, with attacks on programs precisely like the one you would want to go into, arts programs or MFAs, the things that your credentials would fit. So, is there a future for you as a writer…how are you thinking about those things? I don't mean to be depressing, but it's kind of a weird mashup of success on every level that a writer could hope for and a sobering reality that some of that success is perhaps illusory.

River Selby: It's really important to talk about these things because I don't think that we talk about class enough in general, and definitely not in academia or in writing spaces. Because of the experiences I've had, I never have just one plan for myself. I have like seven plans for myself, and that is where I am right now. So I am going on the job market. I see very few jobs coming up. I know the reality of that. And I also know that I would regret it if I didn't at least put myself out there and really give it a shot to get an academic job. That said, I'm not going to take a job unless it's a unicorn job, and I really want it. I worked as a nanny for 20 years and I love nannying. I truly do. I love working with kids. I love working with babies.

When I decided to leave fire and become a writer, I made a commitment to myself. And I'm not saying this in like a stubborn way. I made a commitment, I'm going to do this forever, but it still feels true to me that this is what I love doing. I love writing, I love creating worlds and narratives. As long as I love doing that, I'm going to do whatever I can to sustain myself and being able to do that.

Joshua Doležal: Let's say you get this unicorn job and you're teaching at a program that can afford to not require a four-four teaching load, students would be paying a lot for that experience and would assume that you would have the same level of affluence that would go with the means to afford it. And that's just not the case. I think it's one of the best kept or worst kept, not a positive thing, but it's one of the secrets of higher ed that many people don't understand. And a good reminder that the commercial book deal is not going to save you from all of that.

River Selby: If I could give myself any piece of advice when I was working on my proposal, it is…don't count on making any money from the book, do not count on making any money. Like, if I could go back in time, I would've just put that $20,000 straight into savings and do a high-yield savings account or something and not touched it. If you come from poverty, it's almost inevitable that you'll develop some sort of magical thinking strategy for surviving. Yes, let yourself believe the best things for yourself, but ground yourself in reality financially as much as you can, especially if you come from poverty.

Because our society offers no safety net for people that don't have one in the first place. So we gotta take care of each other and ourselves, you know?

Joshua Doležal: That’s “the thing not named” for today. Thanks for listening. I’ll be back in a few weeks with Sam Kahn. Stay tuned next week for another craft essay.