Walking Off The Grid

The following is a new chapter from a memoir in progress. These monthly installments are only available to full members. For access, please consider upgrading your subscription. I’m also proud to be a Give Back Stack. 5% of my earnings in Q3 will go to the State College Food Bank.

See my accountability page, with receipts for Q1 and Q2, here.

Walking Off The Grid

Twenty years ago, after my last season as a wilderness ranger in Idaho, I drove over Lolo Pass, down to Missoula, and across the plains to my new faculty job in Iowa. I went back a couple of times for brief visits, but I never had time to hike into the heart of the place that I’d embraced as my spiritual home. Once I started a family, it seemed I was gone for good.

But divorce closes some doors and opens others. This summer I knew that when the kids spent their vacation block with their mom, I’d have a chance to walk into the wild once more. After plans with a friend fell through, I started preparing to do it alone.

The Selway-Bitterroot is remote. The largest roadless area in the lower 48. Combined with the adjacent Frank Church and River of No Return, it covers 3.6 million acres of wilderness. It’s pretty much the opposite of visiting a national park, where every trail is manicured and thousands of tourists snap selfies at scenic views. That roughness captured my heart in my late twenties as I finished my Ph.D. I’d hike with my crew to a remote cabin in June and stay there, off the grid, until late August. It was like stepping out of my life, out of time.

I knew I was in for some hardship, but after calling the district office I learned that significant portions of the trail had burned the year before and a microburst had toppled hundreds of trees the year before that. The trail crew was still whittling away at the mess, and no one could tell me just what I’d find along the routes I was considering. I’d been planning to cover 70 miles in five days, but the trail report changed things. I’d have to scale back the distance, but the unknown just heightened the appeal. I bought a solar charger and a satellite transmitter, so I could check in twice a day, and packed my bags.

This wasn’t a vacation for me. It was a quest. I wasn’t sure if my return would rekindle the passion that had haunted me for years, if I’d want to come back more frequently now, or if I’d find enough closure along that wilderness path to finally let the place go.

My cousin offered to loan me a truck to save the steep rental fees. But I found his garage in disarray when I arrived. The spare pickup had blown its clutch, and he had oily parts spread all over the floor. That left only one reliable ride: a 1977 Ford Ranger.

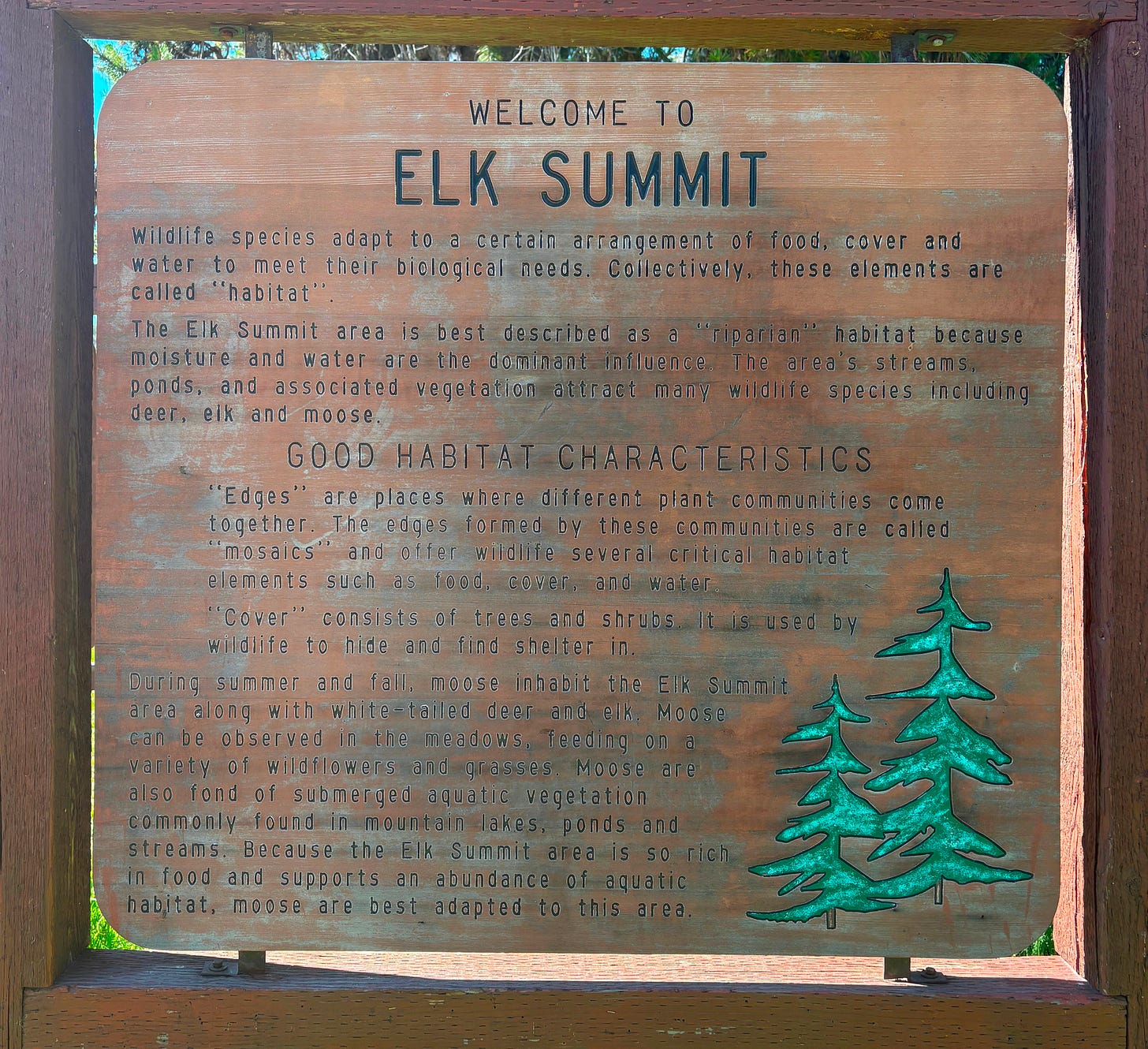

Calling the truck reliable is a little generous. He’d traded some heavy equipment for it and a few other fixer-uppers a while back, like a team offloading a franchise player for a few unproven prospects. The engine ran great, but the side mirrors swiveled if you hit any bumps, and the gas gauge didn’t work. This meant that if I didn’t want to end up stranded on a dirt road somewhere, I had to keep some steady math going in my head, roughly ten miles per gallon against the distance I’d covered since the last fill-up. Not a big deal running odd jobs close to home, but it was five hours from there to the trailhead at Elk Summit. Even if I filled up at the last available station, it required extra faith to believe I’d make it up the mountain and back down.

But I like old trucks, the price was right, and I wasn’t glamping anyway. The trip was already an attempt to turn back time, so driving a truck nearly as old as me felt appropriate. That’s what I told myself as I shimmied over washboard ruts, fishtailing through the gravel.

I left before dawn and drove along the Bull River toward its confluence with the Clark Fork. Nearly all the main roads in that country follow rivers. If you buy yourself a retirement home with water frontage, chances are good that you’ll hear train whistles through the night, because the railroad follows the waterways, too. It’s one thing I love about mountains, that the traveler must accommodate himself to the terrain. There are none of the right-angle grids that define the Midwest, not many long straightaways to put you to sleep. Every mile or so you’re leaning into a curve or crossing a gorge as the great rivers make themselves known.

I followed the Clark Fork to a town called Paradise, where the main channel takes a hard turn south, and the easterly fork forms the Flathead River. It’s a scenic drive south to St. Regis through mature stands of Ponderosa pine and crags where mountain goats show their scruffy beards.

There were no cinematic reveries, no flashbacks to my glory days with the trail crew. My mindset was prayerful as the sun rose. I asked for protection, for wisdom, for the meaning of my journey to be revealed to me. This is a new habit for me this year. After four years of loss and all that aching grief, I’m making the effort to remind myself of what I have, not what I lack, and to rest in that gratitude. At other times, I ask for help or guidance. It might be a stretch to say I wanted a vision in the wilderness, but I was asking for something like that as I drove, some clarity about what is and is not meant for me in the years ahead, what to hold onto, what to let go.

I pumped my fist and whooped as I rolled over Lolo Pass, going the right direction this time, down along the Lochsa River toward the Elk Summit Road. Even those place names felt like medicine to me. Lochsa. Lolo. Selway-Bitterroot. I was making good time, sure to hit the trail by late morning, ready for my adventure to begin.

The trouble began five miles from the trail, long after I’d left the highway. The old Ford was a three-quarter ton, which meant it rode stiffly, as if the shocks had worn out. The little coin drawer clattered out on one of the potholes, more wires dropped down from the dash, and the mirrors spun every time I rattled over a rough patch.

This was all tolerable enough until I heard a scraping sound. I braked hard and jumped out to find a stick wedged between the back wheel and the undercarriage. Easy to remove and better than losing the muffler or some more essential part. I dusted off my hands and leaped back behind the wheel.

But the truck wouldn’t start. No sputter or cough. Not even the electrical whine that live wires give off. The old Ford had died.

This was not good. I pumped the gas, cranked the key. Nothing.

I grew up around trucks, but I know little about engines, so looking under the hood is just silly. The only trick I know for a stalled vehicle is to get it rolling, then pop the clutch, so I put the truck in neutral and started rocking it toward a dip in the road. A 1977 Ford weighs around 4,000 pounds, so this took some doing, even on flat ground. By the time I got the thing going and hopped in the cab, my arms and legs had turned to jelly from the strain.

When you grow up poor, you learn to make do, and this can help enormously during hard times. Whining and carrying on won’t change anything, so you focus on the task at hand, refusing to accept the possibility of failure. But there’s a fine line between determination and magical thinking, and sometimes refusing to quit just digs a deeper hole.