Episode 5 Transcript

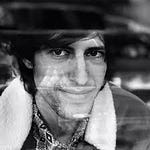

Joshua Doležal

I’m Joshua Doležal, and this is Catchment, the podcast for The Recovering Academic Substack series. My guest today is Dr. Gertrude Nonterah – or, as she asked me to call her, Gee.

Gee completed her doctorate in Microbiology and Immunology in 2015, but after funding ran out for her postdoc she turned to freelance writing. And she has now worked full-time as a medical communications professional for more than five years. Like me, she struggled with some guilt about leaving a path that she had sacrificed so much to pursue. But she was also tired of jumping through hoops for health insurance – of not being able to donate to causes she believed in or just do something fun with her husband and son. And when she began to see ads for tenure-track positions that paid less than her salary as a post-doc, she knew it was time for a change.

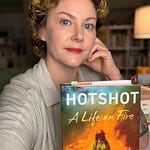

Gertrude Nonterah

There's something wrong with a system that says go to school just to be poor, you know? And then you watch people that dropped out of high school. And they've started businesses and they're making $50,000 a month, and you're just thinking to yourself, there's something wrong here. There's a disconnect… Asking people to get all this education and then underpaying them is a disservice to humanity.

Joshua Doležal

During her transition away from teaching and research, Gee created The Bold PhD, a blog and YouTube channel devoted to helping graduate students and recovering academics like me find careers outside academe. She is also a thought leader on LinkedIn, where she tackles ethical issues like fair compensation and offers practical advice for job seekers.

If you’ve been following this show, you know that I offer my guests a modest stipend. Gee asked me to invest hers back into my business, which was very kind of her. And so I’m sharing our full conversation with everyone today in thanks to Gee and also as a reminder of what paying subscribers enjoy. Because she’s right – I am building a business that relies on your support. If you’d like to hear the full podcast each month and receive exclusive content, like stories for The Chronicle of Higher Education, private discussion threads, and literary work that I share throughout the year, you can upgrade your subscription at joshuadolezal dot substack dot com, slash subscribe. Or just click on the subscribe button in the podcast transcript. If you do, you’ll find that I’m offering a 20% discount on annual subscriptions through Monday, May 15. I look forward to welcoming you to The Recovering Academic community.

Now back to my conversation with Gee Nonterah.

Joshua Doležal

Well, so I think very few of us in our earliest answers to that question of what are you going to be when you grow up really thought of ourselves as academics. I mean, I'm from a working class family in Montana. I certainly was the first in my family to consider that. How about you? When did that start? When did you first start thinking about yourself as an academic or wanting to do that?

Gertrude Nonterah

Right. So I always wanted to be a physician. When I was growing up, I wanted to be a doctor. And, you know, it was encouraged in my household. My mom was a teacher. My father is a scientist, who had a PhD. And so I knew I wanted to be a doctor, but I didn't want to be his kind of doctor. I didn't want to get a PhD and be a scientist. At least that's what I thought when I was growing up. And then I'm originally from Ghana and West Africa, so that's where I grew up -- well, the first half of my life. And I came to the United States for college. So essentially even through college, my whole -- I was a pre-med major and all that. And then coming up to the end of my bachelor's degree, I realized going to med school is super expensive in the US and by the time you get out, you are going to be owing a half a million dollars in student loan debt. And I didn't want to carry around that debt with me for the rest of my life because this is really what happens to people, right? They carry student loan debt with them throughout their whole lives and it becomes sort of a chain that keeps people from moving forward financially, even when they have high paying jobs, right? And so I was like, okay, what else can I do that is not going to set me back so much money? And getting a PhD came to mind. And back then I really didn't think through, I just thought of the end goal, but I really didn't think through what that would mean. And I think a lot of people going into PhD programs, especially when you're coming right out of college, we are still kids really. Now that I'm like almost what… I graduated from college in 2006, so almost 20 years out of college now. Now I'm like, wow, I was a kid. I don't know how I had to make all those decisions. Those were big decisions to make, right? But you're like a 21 year old, maybe 22 year old, and you have to make this decision that affects the rest of your life. Anyway, I chose to get a PhD and we'll talk more about what happened after that, but that's a little bit about my story.

Joshua Doležal

Did you feel growing up then that your parents put some pressure on you to be a professional? It sounds like that was sort of the expectation from the beginning, that you would follow that path.

Gertrude Nonterah

I don't think they put pressure. I think I was encouraged. I think there's a difference. I don't think they put undue pressure, but they also didn't expect…they knew my abilities the way my household worked was, once my parents knew your abilities and what you were capable of, they didn't want you to underplay that. I think that's how my parents were, right? If they knew you could be an A student. Why settle for a C, right? That was my dad's philosophy growing up in the house. And so we weren't pressured, but we were definitely strongly encouraged in a loving way to pursue careers we wanted to pursue so that we would be financially okay, you know? And because one of the things that I saw growing up was my dad, who came from a really, really poor background, lift himself up through getting a PhD and becoming a scientist like that changed his life. So for him, getting out of poverty was education, right? So he really encouraged us. Never really pressured, but I think encouraged…and I wanted it too, right? I wanted to be a professional. Of some sort. Just didn't expect it to be what I am now.

Joshua Doležal

I was speaking in my last episode with Liz Haswell, who is a plant biologist at Washington University in St. Louis and is just preparing to leave her position after many years. And she talked to me about a kind of awakening in high school where she really discovered biology is her thing. Did you have moments like that with your father where the wonder of science, you know, it wasn't just an abstract vocational aspiration, but it was… you owned it, you felt it physically, the pleasure of discovery or experiments -- was that part of your relationship with him growing up?

Gertrude Nonterah

I always loved to learn in general, I don't think science was the thing. I think it was everything. I loved to learn and read about everything. I remember growing up we would go to the local libraries, when we were, like, we had one regional library, so we would drive like 30 minutes out to the library to pick up books. And so I read about anything and everything that was intriguing to me. Including science and science is especially intriguing to me. Cause I wanted to know like how do we have lightning and thunder and how do, how does rain form? So I was very much into that I would say. I was a generalist. I was not good at one thing. I was good at many things. And I think that also how it comes with its own challenge. Because you are good at science. I always tell people that I'm a writer now, and I always tell people that the one subject that I got A’s in from kindergarten all the way through college, A’s all the time, was English. And how it never clicked that maybe I should pursue a career there. I have no idea. But that was the one subject I would get A’s in all the time, right? I would do well in all these other subjects as well. But nothing ever like stood out to me as my thing. I just, I just thought, well, since I think I'm smart at so many things, maybe I can pick a science major, I can pick a STEM major because all the world over, and I don't know how this came to be, I don't know the history, but it seems STEM majors always seem to be in a much more secure position when it comes to jobs than others, right? And, I'm not saying completely, but most of the time that's the case. There seemed to be more paths. I was good at many things. And then I had to settle on one that I thought maybe would open up job prospects for me. I hope that makes sense.

Joshua Doležal

Oh, well, it surely does. And if I'm making funny faces, it's because I was an English professor, you know, for 16 years and near the end of it, it was just a kind of steady drumbeat of this kind of thing. Relentless. You know, it's all about the job skills and the curriculum that leads to the jobs. And so English, Humanities, is always seen as impractical. And of course I fought that myself -- I was going to be a lawyer. I was pre-law and halfway through undergraduate, I just didn't feel it. I could have probably continued and done fine, but where I felt like my full self, my whole self, was in literature class and I guess just stubbornly embraced it, you know? But when you were talking, you're saying, I wonder why I never thought of this. Well, I mean, the world never gave you a chance to think of it, it seems like, right? I mean, it's all STEM all the time.

Gertrude Nonterah

Yup, absolutely.

Joshua Doležal

A little editorializing on my part there, I guess.

Gertrude Nonterah

No, no, no. It's awesome. I like that.

Joshua Doležal

Well, and it is interesting that when you become a PhD candidate, you are really discouraged from thinking of yourself as a whole person or as a generalist. How did that work? So tell me a little bit about your path to grad school and how you sort of chose your specialty, and then did it become increasingly narrow for you?

Gertrude Nonterah

Yes. So it became increasingly narrow for me and I was, I think all throughout my PhD program, I was frustrated not because my PI [principal investigator] was mean. I had a great advisor. I made a joke because by the end of my PhD between the two of us, we had three kids. So she had two kids and I had one kid. And so she understood what it meant to go through pregnancy and have a child, and be doing rigorous work. She understood all of that and she was extremely supportive. But I felt increasingly frustrated because of this, and now looking back, okay, everything is always hindsight. I realize it was because the focus was so narrow -- my whole life, I'd been interested in so many things. Of course I had settled on STEM because I was like, okay, this is going to give me some jobs, you know? And then now I was like increasingly focusing on something so specific, right? Within a specific system and with a specific protein. So it's so minimalistic, right? I also think that at a point I realized I didn't want to be in academia. But I didn't know what to do with that. Because yes, I understood that there were careers outside of academia that you could pursue. There were things people went out to start their own businesses. People freelanced, people went into industry. But I was like, how do I actually do that? And I had no way forward really, or no clear path. There are a lot of professions out there. The one that easily comes to mind was the path I initially thought I was going to go on, which is medicine. You know that you're going to go through four years of college, four years of med school, you're going to go to residency, and then you're going to be an attending physician. So there is a path. But for PhDs, most of the time it's like, okay, well maybe when you finish you should go do a postdoc. And maybe during your postdoc you can try to like finesse your way to getting an assistant professor position, and then you have to write all these papers and then maybe you'll get tenure. So it's not, academia is not such a -- it's clear cut, but then it's not, because there's nothing that's really guaranteed. So I asked myself, you know, I had some kind of like, introspective moments where I kept asking myself if academia was really the path I wanted to go on. So I went through grad school. I was actually a successful graduate student. I finished with published papers. It was really part of the work I did there, but I knew it wasn't my passion. And herein will I say that it's important to realize that you can be really good at something and still not like it. And that's okay. Then I went into a postdoc, stubbornly, I was like, okay, maybe if I go into a postdoc and still try to be a fight to be a scientist, maybe I'll love this. That's almost three more, more years of my life. So finally, got kicked out on my post-doc because we ran out of funding. And that's another problem with academia. When funding runs out, everybody loses their jobs. And finally I got to sit with myself and say, okay, maybe Gertrude, you really should pursue writing like you've always wanted to do and stop trying to be a scientist. Stop trying to be a lab scientist. So I started freelance writing and that has led to the whole career path I have now.

Joshua Doležal

Forgive me for lingering here for a moment, but it's really ironic to me that you felt that graduate school in science was the sure thing, right? The safe bet job-wise. But once you got into a PhD program, you felt that there wasn't a lot of clarity about what kind of jobs except for faculty. It was as if all of your options were shrunk to that. Is that an accurate statement?

Gertrude Nonterah

Yes. I think in my mind, most people became professors. That was the well-beaten path. And I didn't know anybody really outside of that path. I knew one or two people, well, I didn't know them. I knew of them because they used to be part of our programs who had gone into like work for the FDA, or maybe they worked with some industry company, some company out in industry. But it wasn't clear how they got those jobs. So I didn't…the only sure path was academia.

Joshua Doležal

If you were to rewind your journey, it sounds to me like you reached a point where, and I used this metaphor once in an essay… It's like you're walking down a hallway that continues to narrow and then you go through doors that lock behind you, and you can't really go back. So you just have to go through the next door, which, you know, for you was the PhD and then the postdoc and at some point that hallway was a dead end. But if you were to rewind, was there a point at which there might have been more opportunities to you if you had only a master's? Would there have been a space for you to not have been funneled into academe, but you could have maybe stopped and had other opportunities in science outside of teaching or research?

Gertrude Nonterah

I didn't even think of that at the time. My kind of personality that I am…I always thought I had to see everything through. Right? If I started something, then I couldn't quit because quitting, this is the other thing too, so I think you kind of touched on it, but also even when you have like a really supportive family, a loving family and everything who've supported you all through, when you have that there and I appreciate it. There is also some kind of guilt that comes with that. With trying to quit anything, right? Because you feel very beholden to the fact that there's so many people that have had to make so many sacrifices for you, and how dare you try to do anything outside of this path of excellence that you have chosen. So there was also that, there was also that feeling of…if I leave this, this would be really letting down my parents and my parents are giving me everything. So I did not even consider that at all. Like, that was not an option in my mind. Like the option was just like try and finish.

Joshua Doležal

Wow. Can you take me to that moment, that day when you knew that it was over and how that felt?

Gertrude Nonterah

Yes. I think there was, there was a part of me that was excited that I had come to that conclusion and then there was a part of me that also thought, wow, I've spent so many years and is this, you know, I think you, you probably know about the sunken cost fallacy, right? I've done so many things and so I just have to keep going and maybe if I, you know, so there's all that that goes in your mind. So I think finally when I came to the place where I was like, I want to be a writer. When I lost my postdoc due to funding cuts, I remember one day waking up and I think it was around tax season and we had gotten our tax refund. My husband and I. And I just told him, I said, I think I want to be a writer. I want to do medical writing. And he was like, really? What's that? And even I have this conversation with a few people and they're like, what kind of profession is that? Like, I've never heard of it. And I'm like, yeah, it's a profession. There are people that are in it. And I want to do that. And of course, Again, you know, you have always have well-meaning people around you and they may say, well that's like, that's not such a sure path, right? We don't, like many people don't know about that. Going to be a professor is like everything that most people know about. So I think finally when I came to that place where I myself was making that decision of, well, I've made my parents happy by finishing my PhD, which meant a lot to me too, to make them happy. I've fulfilled that goal. I have gone through a postdoc and I've realized I don't like this path. Now I'm going to do something that I like. Right? I'm going to do something that I want to do. I felt happy that that had happened. But I also felt very grateful and happy that I had finished a PhD. I just wish it didn't take me that long to realize.

Joshua Doležal

I hope it's okay for me to ask this. I write for The Chronicle of Higher Ed and wrote a story six months ago on why faculty of color are leaving academe. And one of my sources was talking about a job at University of Arizona where she felt like you're saying -- she was first generation and had achieved all these things that made her family proud, had gotten this job that was coveted. It was in hip hop and religion, which was just like this really niche area that was perfect for her research. She gave up a huge friend community on the East Coast. She and her husband did their degrees at the University of Buffalo and moved out to the desert, which was not a place where she felt comfortable, and they had a daughter and her husband was finishing his PhD, going back and forth, and at some point she had a heart attack. And she just thought to herself, I don't have to die here. I don't have to die doing this thing. But it was for her, partly driven by this fear of letting people down. That she was a kind of representation for her community, that she felt she brought her whole community into the university and then by leaving, she was losing a seat at the table or, you know, as one voice in the choir taken away. Did you struggle with any of that as a Black woman in science?

Gertrude Nonterah

Yes. So actually one of my friends told me, but Gee, she was like, if you quit, you know, who's going to inspire all the Black students in academia? And I felt guilt around that, right. Because I'm like, yeah, that's true. If I quit…because let me tell you an experience I had when I started. I taught community college for three semesters, and this was right before the pandemic. We still had in-person classes. I showed up for the first day of class, right? And there is this Black girl standing outside of the classroom. We were waiting for the classroom to open up so we could enter. So when she sees me, she assumes I'm a student, right? And she starts chatting. She's like, oh, are you coming to this class too? And I said, yes, I am. And she's like, oh, you know, so we start chatting and then once the other class comes out and we go in, she, I watch as her face changes as I go to stand in front of the class and introduce myself as the professor. Her face just like was like…What? I get…? I don't know what she was thinking, but her whole demeanor changed. She's like you're going to be my teacher. And I think she was just surprised in 2020 that she could probably have a Black woman professor in biology. Right. I still think we're unicorns in this space and people don't see much of us, and especially students of color or Black students specifically don't see a lot of black professors. Now, some of that has changed, but the percentage is so quite low. So there was a part of me that felt, well, you need to do this for the culture. You need to do this for the community because if they don't see that, then you know… For me, growing up in Ghana, I was surrounded by people that looked like me, so nothing in my mind seemed impossible. And I grew up with a scientist father. We lived in a community that had a lot of scientists who worked at the same institution. There were women amongst that, so it wasn't such an odd concept for me. Coming to America and seeing all the different ethnicities and seeing how there was, even though we've moved past segregation, there was still some of that even within our institutions. I realize how important it was to sometimes represent that for some people, right? Because they may not have been surrounded by people like I was, where their mind is like: Can I be that person? Can I be that science professor? Can I be, can I go do something in engineering? Can I do this thing in the humanities? When people don't see that, they don't aspire to it. So yes, I did feel some guilt around that. Then you talked about her having a heart attack. I want to talk about the time. I did have an anxiety attack in a parking lot when I was a postdoc. I went to work. Parked my car and started crying because I did not want to be there that day. I did not want to be in, I did not want to be a researcher, and I've had that building, that feeling had built up all through my PhD up until this point, and I started bawling. I started crying. I was shaking. I remember calling my mother on the phone -- as a grown up over 30 year old woman -- calling my mother on the phone and telling her that I did not feel like going to work today. And I was sitting in my car and crying, you know, not because I had a toxic environment, not because I, I always say like, so, and all of these things. That also builds the guilt because you don't have a toxic work environment. Everybody's so nice to you. Your family's so great. Like, why are you having all these feelings, you know? It's so complex and people don't realize it's not just a matter of just getting up and saying, I'm leaving academia. There's so many emotions that come with that, that stem from various aspects of your life.

Joshua Doležal

Thank you so much. So at the end of the postdoc, you ran out of funding and it sounds like you already had this path toward medical communications or medical writing in mind, so can you tell me how you transitioned then to that?

Gertrude Nonterah

Right, absolutely. So while I was postdoc-ing, I started a side hustle because I live in San Diego, California. And one thing about California is that everything is hyperinflated. It's worse now with the inflation in the system, right? So even in 2018 or, well, 2015 when we first moved here…so we moved from Philadelphia to San Diego. Everything was three times the price. When I started the postdoc, I realized it was expensive. So I started a side hustle to just kind of contribute financially to my family and that side hustle was writing. So I had started a blog and I leveraged that to start pitching businesses, to write content for them. So by the time I lost the postdoc, I realized, oh, while my income was almost matching my income from the side hustle — writing was almost matching how much I was making as a postdoc. So if I just stepped it up a little bit, maybe I could, based on income, and that's what I did. And then I started on my YouTube channel. So like there were income sources kind of like tiny income streams coming from everywhere from all these places. But that was so helpful during that period of time where I was at home and with my son taking care of him because he has some special needs, but at home, taking him to school, picking him up, but also having that time to freelance. So that's how that started. And then a few months after the job loss, I began to narrow down specifically to focus on medical healthcare companies and creating content for them because of course they need to market their businesses. And, I was like, I could do this. So I started doing that and had a health technology company, a doctor's practice. I had a home healthcare company, so I had all these healthcare bioscience companies that I was helping to create content. But just around 2021, I had an opportunity to join a company as a, a science writer, and I did. And my career in medical communications formally took off, but I had been freelancing leading up to that.

Joshua Doležal

Well, I know that you've written and also spoken on some of your videos about, about compensation and fair compensation and so much of academic socialization is really focused on doing everything pro bono, right? You're serving, you're making a sacrifice. It's all for a higher good. How did you think through maybe giving yourself permission to just focus on earning potential and really embracing that side of your business?

Gertrude Nonterah

Absolutely. When I give this response, it's always going to sound so crude because of, like you said, academic socialization, but I think I was just tired of being poor. That's it. That's really it. I was really exhausted of…I was like, I have all this education. I think one of the things that got to me was the fact that… I touched on the fact that my, my son had, does have some special needs and I needed health insurance for him, and the hoops I had to jump to get the state funded health insurance were so exhausting, was so frustrating, was so humiliating, was so dehumanizing that I was like, I hate being, having to depend on the state for health insurance on my child. I hate that. I had a PhD, and yet, you know, yes, my freelance income was okay and it helped to pay the bills. But if we wanted to do something fun as a family, we couldn't do that. I hated that. I hated that so much. If I wanted to give to some cause I cared about, if I wanted to purchase something… I'm not a frivolous spender at all. I'm quite frugal, but I just hated being poor. Absolutely. So at a point I was like, there's something wrong here. There's something wrong with a system that says go to school just to be poor, you know? And then you watch people that dropped out of high school. And they've started businesses and they're making $50,000 a month, and you're just thinking to yourself, there's something wrong here. There's a disconnect. So I think all of that made me upset. I think that the one thing that push maybe pushed me over the edge a little was at the time when I lost a postdoc and was looking for opportunities and still couldn't come across any opportunities. There was one job I saw, one job ad I saw for an assistant professor position that I think was paying about $10,000 less than my postdoc. It was at that point that I said to myself, you are requiring somebody with a PhD. With publications. With all this experience to come and get paid $10,000 less than a postdoc? So all these things frustrated me and some people find that quite rude and crude to say, but I don't think it is. I think we need to talk about it more because asking people to get all this education and then underpaying them is a disservice to humanity.

Joshua Doležal

It's immoral, right? And I have to say…so I had a tenured position. I was a full professor when I resigned. And there was a long prelude to that. But part of it was that so much of the emphasis on what we were supposed to be doing in molding students in, even in an American literature survey course, I was somehow supposed to be helping them become more employable. And, I mean, I just got to the point where I told one first year seminar, I don't get up in the morning to help you get a job at Wells Fargo. That is not the thing that motivates me. What motivates me is introducing you to new ideas, giving you something that's lifelong, that's not merely the entry level job skill that will be obsolete as soon as you take the next job. It's really examining your life, seeing yourself in the history of ideas. That's the thing that gets me up in the morning. And I guess the other part of it, where I guess I'll turn to my crude, crass part is I started to think more about my own salary. Why was it that my graduates with nothing more than a bachelor's degree were earning basically the same as me right out of college? That's messed up too. That's not motivating to me. So earnings were never my goal as an academic, but it seemed to become the goal of the academic enterprise for students by the time I left and I just didn't believe in it anymore.

Gertrude Nonterah

Yeah. So there, there was that, so I began to talk about that on LinkedIn, you know, and I started my YouTube channel, The Bold PhD, and began to talk about that. And then the funny thing that happened was I thought that this was a topic that maybe was just me, but I began to have PhDs actually write to me and say, yes, this is happening to me too. Like what? This is not just me, I'm not like a crazy Black woman? You know, there were people reaching out and saying, yes, I finished my PhD and struggling so much to find a job, or I finished my PhD and I'm struggling to…for somebody to like pay me what I think is... You know, I did a video recently when I was talking about two years out of academia, how do I feel? And I remember there was a post I had made on LinkedIn and somebody made a comment about the fact that, basically you all can leave academia because, you know, it's competitive in here and we need space for the more serious academics. And so there's this flawed thinking within academia that when you leave academia it's because somehow you are a capitalistic opportunist. Or you don't want to serve people. You know, good riddance. And I'm thinking to myself, no, that's not, that shouldn't be the response. The response should be, why are we letting intelligent people leave? And so then you have people saying, oh, I don't want to leave because I don't want to seem like I'm leaving just because I'm a capitalist. And I'm like, but academia is a capitalist institution. What made you think it isn't? Like I don't mind anybody getting paid how much money they should get paid, but there are individuals within academia who get paid over a million dollars a year. And then you have the people that are on the ground, the foot soldiers who would get paid less than $50,000 a year. There's something wrong with that.

Joshua Doležal

Well, so tell me a little bit more about your other gigs. So you do this YouTube channel, you do speaking engagements, you have kind of a diversified portfolio. You're doing the medical communications thing full-time now, or are you back to freelance?

Gertrude Nonterah

Yes, I'm, so right now I am in a full-time role. I think it went back to the dehumanizing experience I had with just trying to get health insurance. So I realized a full-time gig was sometimes more secure in that sense when it came to getting the kind of health insurance that I needed for my family. So I did get a corporate gig, which actually is great because it's very flexible. So I'm very, very grateful for that. Once a while I'll still do a freelance project here or there, but right now I'm focused on that. And then of course The Bold PhD YouTube channel. I produce content for that. I do speaking engagements, so I do get invited to speak at different universities. Just last week I spoke at the University of Illinois in Chicago. I'm really, really grateful for these opportunities that I still get to work because I think what's happening with me speaking out, not just me, but there are quite a number of people, including yourself, right? It's beginning to resonate in the minds of some of the people within academia. I even had somebody tell me they have included their videos as part of their curriculum for like a writing course or something, which Wow, I never thought that that would ever be the case, right? Like, oh look, this unsuccessful academic, and now my videos are being used in that. So it taught me a lesson — it taught me a really great lesson. And, you know, don't be afraid to create a path that maybe other people hadn't created, haven't created yet at the time when I started doing this there were very few people talking about this or being as vocal, right? Or as crude, because I was like, I hate being vocal. But I want to have money too.

Joshua Doležal

So one thing that you also offer is coaching, it seems from your website. So can you tell me how you help other academics translate their skills into rewarding careers?

Gertrude Nonterah

Great. So right now I've actually toned that down a little bit. I don't do a lot of coaching anymore, but when I did do it and when people ask me, I'll like evaluate the situation and see if I have the bandwidth for it. I've just had so many things on my plate, so I haven't, I've had to drop a few things. But with coaching, I would chat with the individual because sometimes people didn't even know where to start with, with seeking a job outside of academia. Right. And so we would talk about what they wanted to do, what their resume should look like, because so many academics, we lead with all our accomplishments. But in the, in the non-academic world, people don't care about your accomplishments, right? They care about the skills that you bring and how you're going to help them solve a business problem. So I always try to show them how to…let's pull out the skills out of you, right? The things that you have gained all throughout your PhD, all throughout your educational experience. Let's pull that out. And in light of the job description, let's write a resume that shows how your skills from your educational and occupational experience make you the best candidate for the job. So that's how I tend to coach people is don't, don't just don't just like glance through. I don't glance through job descriptions. I take job descriptions extremely seriously. So whenever I read a job description, I always tell…the way I coach people is, I tell them, think of every requirement in that job description as a question that is being asked you. They're asking you, can you do this? Can you do that? Do you have A, B, C skill? Now, you, with your resume are going to answer those questions and say, based on A, B, C experience, yes I can do this. Yes, I can do that. And yes, I have this experience. Right. You don't have to meet every single criteria on there, but have enough to look powerful on that resume so that the moment your resume, somebody glances at your resume…I think that the statistic out there is that it takes, what, 10 seconds or 20 seconds or something for, for an HR professional to look at your resume. So within those 10 seconds, you had to wow. Right, and they're not going to spend time looking at the 10 papers you wrote that are in Nature, Cell, or any of these fancy journals. They're going to care about the fact that because you wrote papers for those journals, you have skills that allow you to write the application note. It's a type of document I write: the application note that they need for their company. Right. So that's how I coach people, is really to take the job description and read it, spend 5 to 10 minutes reading it, then craft a resume that says, I can do what you need me to do. Another thing too that I love and which has been helpful for my career, is the idea of personal branding as an academic. I think you have to have a strong personal brand as an academic. And this is not just online. This is just with your work ethic, with wherever you are. That's where it starts. But, you should extend that to some online platform. And my preferred online platform is LinkedIn. You are doing this on Substack and that's great. Medium. Wherever it is you want to build this, you can build it. But I'm very familiar with LinkedIn and so I really encourage people to fill out your whole LinkedIn profile. You know, put in those experiences, highlight those skills that make you the person, begin to interact with other people. Also put out your own thoughts, right? Become a thought leader. And don't worry if people think it's rude or crude. If you don't want to be poor, well then go on there and write that and you're going to get some, you're going to get some people riled up, but you're also going to fall on the radars of people that absolutely love everything you have to say, and they want you to come and talk to their students, to have you in their company. This actually happened to me. The first job I got as a science writer. I still have great relationship with people in that company, but one of the reasons they gave me the job was because one of the people that would become my colleague said, I went to your LinkedIn and I read all your posts and I was like, I want to work with this person.

Joshua Doležal

Hmm. You know, I worry a little bit about that because so many of my posts are polemics. I'm writing about real problems in academe or – my latest one this week was about a group of professional athletes that with their investment company purchased an Iowa farm by which they will receive federal subsidies for the corn and soybeans that they grow, which seems to me just completely backward. These are people who benefited from land grant universities, which exist to promote diversity in agriculture. They know nothing about farming, but all the wealth that they've acquired through athletic celebrity is now going to be used to force a lifelong farmer to lease the land from them. It's upside down. So I'm pretty forceful about things like that and I worry that I'm kind of isolating myself by being so opinionated. But you're saying that that can be an asset.

Gertrude Nonterah

That can be an asset. Nobody is going to be happy with you a hundred percent of the time and there's always a section of the population you're going to annoy. Absolutely. That's fine. But I think that especially the right company, not everybody can take, not everybody can handle that. But then you're also going to find some companies that actually love that people have a voice outside of just their work. There are certain lines I absolutely do not cross. You know, I, whether I have views on that, political, social, whatever, religious views on anything. I'm not going to go there, there's a line I will not cross because immediately that happens. That just brings up unnecessary controversy and also just disrespect. Right? I don't, I'm not that kind of person, If it's just for causing controversy's sake. No, never, never ever for me. But if it's something that it's like, no, I was tired of being a poor academic, I'm going to write about that because I think that needs to be fixed.

Joshua Doležal

I'm curious what do you love about your life now? Compared to that moment in the parking lot when you didn't want to go to work?

Gertrude Nonterah

That's a great question. I love life. I love life now. I have a great professional life. I enjoy what I do. Yes. I like, there's drudgery of work, everybody goes through that. But I enjoy what I do. I never feel trepidation going into work. I never feel like, ugh, not again, which is all feelings I used to have as a researcher. Nowadays I'm like, oh, I get to go to work and I get to write cool stuff, or, you know, I get to go see all the data. I’m on a team of R and D scientists. I don't do the research. I just create content for them, but I get to see what these scientists have done today and all the complex data they generated. And I get to like wade through all of that and create content. Financially my life definitely has changed because now I don't feel as financially stressed. I think there is some research to show stress causes all kinds of diseases, including anxiety attacks, including heart attacks, including strokes. And I am not stressed. And so then I reduce one risk factor for those problems, right? So I'm very, very excited about that. One more thing is, wow, for the first time in my life or in my adult life, let's see, I was able to take vacation with my family. Last year I couldn't do that in academia because I didn't have the money to, and I would feel guilty even taking time off sometimes. But now, like we go on like one week vacations and I come back and I'm rested and I'm happy and I go back to work and people are like, oh, how was your vacation? But in academia, sometimes it would be like, oh, you're taking a vacation, but you have a paper to write. Yeah. Don't you think you should focus on that?

Joshua Doležal

Well, and so yeah, summer is not a vacation, right? It's time in the lab or time in the library archive, or you're supposed to be producing something even when you're on sabbatical. It's not for recharging. It's for production. I know in my case, a lot of the pressure, the stress, and the negativity from the academic environment really hurt my family and at least five years leading up to when I resigned, and I would've to say that the impact on my family life and the benefits to life here -- we moved from Iowa to Pennsylvania -- was one of the number one factors of making that decision for me. And I'm curious for you what the impact's been on your family life after this transition.

Gertrude Nonterah

It's been great. It's been great. I remember a comment my husband made the other day and he said something like, when you were academia, you were really stressed and you weren’t, you didn't feel, you know, I would feel he told me I would feel it in my body when we went to bed. Like I was stressed and in the moment I wasn't, that went away. So much of it was built up during that time. And I agree that once I left, I'm not there anymore.

Joshua Doležal

Thanks for listening. And my heartfelt thanks to Gee for sharing her story. You can sign up for Gee’s newsletter at theboldphd.com to receive biweekly career and professional development tips. As a bonus, Gee will send you a free list of 34 non-academic careers that you can consider regardless of your discipline or research area.

My guest next month will be Ginger Lockhart, former professor of quantitative psychology and founder of Quantfish, a statistics training platform for researchers. If you know of someone who might be a good guest for the podcast, or if you’d be interested in sharing your own story with me, please let me know at dolezaljosh@gmail.com. That’s Dole, as in the pineapple, Z as in zebra, A, L, Josh. At Gmail.com.

If you are still a free subscriber, I hope you’ll consider upgrading at joshuadolezal dot substack dot com slash subscribe, where you can take advantage of my spring discount.

Gertrude Nonterah’s story was produced and edited by me. Theme music is by Doctor Turtle. Thanks again for joining me today, and I hope to see you later this week for our usual Friday discussion.

If you missed

's essay at Inner Life, check out "Wounding the Reader: The importance of writing hard things in a commodified world."