While packing boxes for another move, I’ve gone through a familiar cycle of deciding what to keep and what to throw away. Old photographs always make the cut, but I puzzle over some of them. I can’t believe that the boy flexing in neon Spandex and a shredded tank top could ever have been me. But maybe I’m fooling myself by imagining that I’ve left him behind.

I was thinking of these things the other day while following Jess Sims through a workout on the Peloton app. Part of me marveled at how far fitness culture had come since the 1990s, when weight rooms were gendered spaces that literally reeked of testosterone. One offender at my college gym filled the place with such rank B.O. that we nicknamed him the Toxic Avenger. Which captured the Zeitgeist of weightlifting well enough.

There’s a lot to celebrate in escaping that mindset. Maybe there’s even hope for progress if a boy steeped in 90s fitness culture can become a man whose favorite trainers are women. Yet I continue to ask myself if those old habits of mind are really gone.

The bodybuilding paradox

The goal of strength training in the late 80s and 90s was dominance. You lifted weights to get bigger, to max out higher than the guy next to you, and to make people scared to slam you into a locker. I felt so happy when I set a record as a high school freshman by military pressing the entire stack in the cage. It didn’t matter that I had to twist my torso unnaturally to manage the last few inches and that my upper back ached for days afterward. What mattered was my name up on that wall.

Gyms simmered with the tension and silence that has long defined male relationships. There were intimate moments when my lifting buddy placed his hands on mine as I struggled to complete a final rep. But we masked those moments with insults and drew our motivation from the self-loathing that pulsed through the grunge and metal of that era.

I am the man in the box. Buried in my shit. What I’ve felt, what I’ve known, never shined through in what I’ve shown. Never free, never me, so I dub thee unforgiven.

A lot of the young men I lifted weights with were compensating for voids their fathers had left in them. Ripped biceps were no different in that regard from jacked up trucks with gun racks. A body that said Don’t mess with me more often meant Help, I’m dying of loneliness.

And so for many years my fitness was a façade, not wellness at all, but a stand-in for other forms of self-harm.

The muscular Christian

These thoughts did not occur to me when I first saw John Jacobs and the Power Team perform. The year was 1992, and I was a high school junior when my church youth group bought tickets to see the Power Team in Missoula. There were no YouTube trailers then, no TikTok previews, just posters like the one at the top of this post. My imagination filled in the rest. By the time our bus arrived at the arena, I was buzzing.

I watched John Jacobs break 20 (30?) baseball bats over his thigh, slowly, like he was massaging a knot. A man lowered his shoulder and ran through half a dozen enormous blocks of ice. In a particularly twisted stunt, a Power Team soldier lay on a bed of nails and bench pressed 315 pounds more than 20 times.

The point of all this was to glorify God, but these were not joyful men. John Jacobs and his crew carried the same simmering rage through their routine that I recognized in my football teammates, even in the coach’s son, who earned straight A’s with an aw shucks grin, but who screamed at us in the huddle, Let’s kick their fuckin’ ass!

I knew even then that a person secure in their faith does not need bodybuilders to inspire them, and that anyone who answers such an altar call falls away once the endorphins fade. Gazing at that poster now, it’s not the mullets that catch my eye or the phallic swords, it’s the sadness in the mens’ faces. They couldn’t crank their music up loud enough to touch it. Not even the Blood of the Lamb seems to have reached those chilly depths.

But I hung the poster on my wall and measured myself against those men each night before bed. I told myself that there was redemption in each burning curl, that torching the last ounce of my strength might cause God to smile down on me as a worthy son, the way my own father never had done.

There was a cruel logic in all this, because my penance in the gym made me sexier, more virile, even while I remained committed to abstinence. Sometimes exhaustion was even erotic, sending flickers of pleasure through the pain on the sit-up bench or during the last chest fly, when I’d squeeze my core to help finish the set.

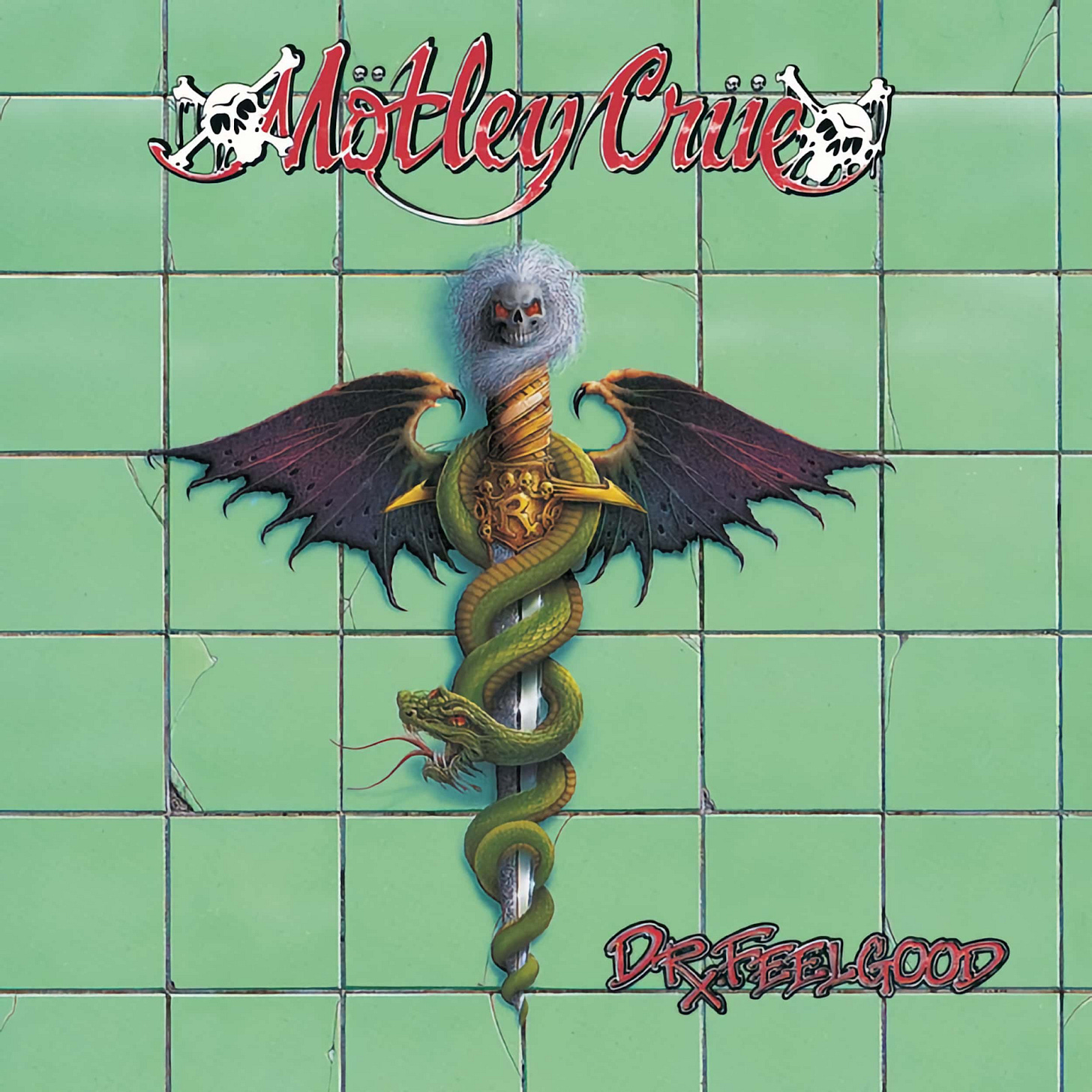

But how different was that pleasure, really, from the dopamine hit I sought from cheap college beer? Or, later, from sex itself? Most of my workout playlists were all about drug addiction, anyway. I never bent a needle to my arm, but I sure knew what it meant to call Dr. Feelgood.

The problem was that Dr. Feelgood never left me feeling alright.

The gym reborn

I’m not sure when this all changed for me. I still love pushing my physical limits, but now it’s about seeing what my body can do at age 48, not because I think I deserve the pain.

I trace part of my evolution to a running group that I joined more than ten years ago. We had a standing rule that everyone ran together on the way out. The club was co-ed, and talk ranged all over the place, from kids to high school sports to pop culture. It was a revelation, after years of disappearing into my rituals, to be present to others during exercise. A few of us always kicked into higher gear on the way back, but always for the joy of it.

COVID killed most of my group workouts. The running club never got back together, even after the danger had passed. And the two friends I’d been training with in the gym got used to their basement routines.

Around that time my ex ordered her Peloton bike, and I started using the app for my home workouts. Peloton has a trainer for every demographic. Latino? Check out Rad Lopez and Robin Arzón. Queer? Matty Maggiacomo’s got you. Representation matters in fitness, like everywhere else. Seeing someone who looks like you doing what you aspire to do is motivating.

I knew that I was supposed to gravitate toward the “bro” trainers, like Andy Speer, Matt Wilpers, and Adrian Williams. All three of them offer a watered down version of 90s fitness culture with the Metallica, Korn, and DMX playlists to go with it. But you know what? I wasn’t nostalgic for any of that. I wanted more of what I’d experienced in the running club, which is what drew me to instructors who weren’t like me, at least not outwardly.

Athletes like Jess Sims and Tunde Oyeneyin.

One thing I love about training with women is how different the messaging is. I know that Jess and Tunde don’t see me as their target audience. Much of what they say is meant for people who aren’t accustomed to pushing their physical limits, who need to be reminded that they can do hard things. But they also caution against comparing yourself to anyone else. As corny as it sounds, Jess’s motto, “No ego, amigo,” really resonates with me. If you’re struggling, scale it to the knees. Don’t contort your spine just to get your name on the wall.

But the biggest difference between the Peloton staff and my childhood heroes is that Jess and Tunde are happy. They’re not punishing themselves or compensating for emotional neglect. What a privilege it is to move, they say. Fill yourself up so you can show up for others.

Just like song lyrics read aloud, most of these platitudes ring hollow if stripped of context. But they land differently when you’re sweating alongside someone who is communicating, at every step, that they’re doing it with you. I even find some healing in the thought that my ex is taking the same classes, responding to the same messaging, even if we both see each other as the thing we’re recovering from.

I think I keep choosing Jess and Tunde because I need proof that the gym is no longer the segregated place it once was, and I want to believe that I’ve left those sad men behind. That I belong to this new, happier, fitness family.

But I wonder if I can shed my past that easily. I remember the verse I heard so many times as a child, which explains what it means to be born again, “Therefore if any man be in Christ, he is a new creature: old things are passed away; behold, all things are become new.” Being born again is not far from Paul DeMan’s definition of modernity as “a desire to wipe out whatever came earlier, in the hope of reaching at last a point that could be called a true present, a point of origin that marks a new departure.” I share in the hope of discovering a truer self, a more authentic form of being, but I’m wary of such radical erasure of what came before. It seems violent, like a long blast of electroshock therapy.

Even so, I’m not sure what to do with the muscular boy in that old photograph. Maybe we all have a core, like the pith of a tree, that remains solid as we add growth rings every year. Maybe that boy lives on in the heartwood of “me” — not alive, exactly, but still part of where I come from, what holds me together.

Another option, as Gail Griffin suggests, is to see myself more like a matryoshka doll — younger versions of me nesting within the more recent shells. But the original core, in Griffin’s formulation, is the ultimate blank slate — “a darkness, a space, a silence.” Even if I carry all of my selves within me, considerable gaps yawn between them — enough to wonder if some of my previous lives now belong in someone else’s nesting doll.

I’m keeping that old photograph for now. Hopefully it will be years before I have to go through those boxes again. But someday I know the question will swing back about what to keep and what to throw away, and that then I’ll be asking with my kids in mind. I don’t know whether this photograph will make the cut then or fall mercifully into oblivion. But I marvel at how the stories we pass on can never be whole truths, how our lives land in the hands of others searching for their own points of origin, their own new departures, their own questions about what is essential and what should be wiped from memory.

Just lost my comment somehow so will quickly say that I love this essay. There may be a genre emerging here, "fit lit"? Or maybe that's already a thing. Love the modernity quote, the description of how ex's define each other (what we're recovering from), the use of the photo as a hook, the moving description of what so many would dismiss as toxic masculinity (I too saw the sadness in the faces of those grotesquely misshaped young men), wow. Thank you.

Enjoyed this. I used to run, but then my knees started giving me trouble. For a while, I tried to lift weights, but found it boring. Finally, I’ve found a wellness routine that suits me: yoga and long dog walks. My yoga studio is about 90% women, but since women are much tougher than men, I figure that if I can keep up with them at my age, then I’m doing ok. Plus, I always feel better after yoga, which seems like a good sign, and my studio is a kind, welcoming place that makes everyone feel at home.