Man Destroying Higher Ed Can't Say What Comes Next

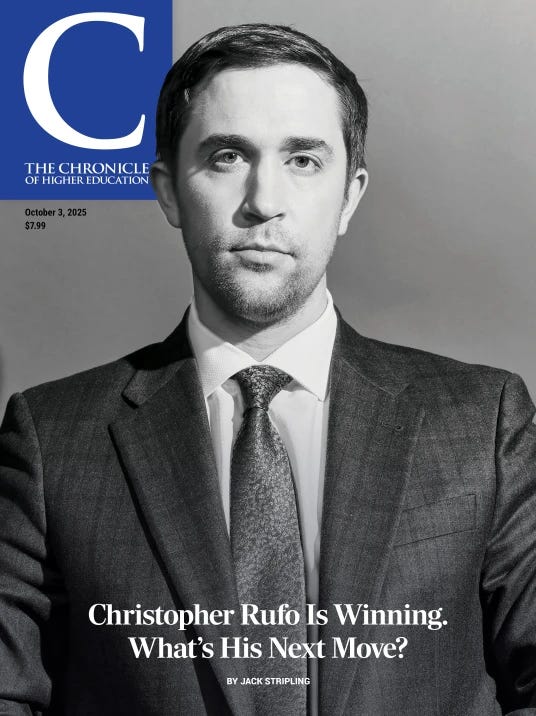

Back in March, before NY Times columnist Ross Douthat officially launched his podcast Interesting Times, he released an interview with Christopher Rufo, a political activist best known for his attacks on critical race theory. Last month the typically left-leaning

featured an interview with Rufo as its cover story. He’s also made appearances on the PBS News Hour, Jordan Peterson, Coleman Hughes, and many more.If anyone can be described as the architect of Trump’s systematic attack on higher education, it is Rufo. His skill as a wedge driver and gadfly is undeniable. But as even major venues have begun to take him more seriously, Rufo has failed to offer a coherent vision for American education.

This is the week in my calendar when I’d typically post a review or interview. But I’ve been troubled by Rufo’s term “classical liberal arts” for some time now, and the extent to which pundits have allowed him to leave it so vaguely defined.

The Chronicle asked what Rufo’s next move might be. Based on his inability to answer that question coherently, I expect that he’s just as interested in the answer as we might be.

Credentials

To his (slim) credit,

describes himself as a “writer, filmmaker, and activist,” not a scholar. He holds a B.S. in Foreign Service from Georgetown (2006) and a Master of Liberal Arts from the Harvard Extension School (2022). Continuing education is a wonderful thing, and I’ve no wish to disparage any education program offered to lifelong learners, but for a political influencer who routinely accuses other people of inflating their resumes to routinely refer to himself as a Harvard graduate is rich. For instance, Harvard typically accepts less than 5% of applicants for its undergraduate degree, but 100% of applicants who complete three courses with a “B” or better earn entry into its Extension School.Scrutinizing credentials can smack of pretension and is, at least in part, the sickness that Rufo and others are trying to exorcise from education. Yet well-administered credentials are one way of identifying excellence and expertise, which conservatives claim to hold in high esteem. For instance, Rufo’s investigation into Claudia Gay’s plagiarism contributed to her resignation as President of Harvard University. While I found the plagiarism scandal somewhat arbitrary and opportunistic, given that Gay initially fell under the microscope for political reasons, there was little doubt that I’d have failed a student who turned in comparable work and reported them to the academic dean.

So I found myself in a strange position: agreeing with some of the substance in Rufo’s critique, but objecting to the vitriol with which he delivered it, and ultimately finding myself confused by the logical outcome of his argument for education itself.

Excellence in scholarship is one pillar of the traditional liberal arts (we’ll get to the “classical” part in a minute). Such excellence is ostensibly what Rufo was defending in his takedown of Claudia Gay. Yet Rufo’s own credentials are, at best, a little above average and his public writing is effectively tabloid journalism, filled with rage bait and conspiratorial thinking.

The only real credentials he has are insider connections and an influencer-sized platform. There’s nothing classical about him. So why is he seen as any kind of architect for education?

Credo

The Latin root of “credential” is effectively the same as for “creed.” Both derive from credere (“to trust” or “to believe”). So if there is a classical basis for education, surely it begins here: with a set of beliefs that inform a curriculum which, once mastered, makes a scholar trustworthy, believable, worthy of others’ belief.

So what does Rufo believe about education? He hasn’t said much except for a few platitudes about the “great tradition of the Western civilization” (see Douthat). Even in a 2023 NY Times op-ed, Rufo spent more time excoriating universities for DEI practices than articulating the core of his vision. The best he could do was vaguely allude to “the true, the good and the beautiful.” None of which are self-evident. All of which require definition to mean anything.

If Rufo really wanted to return to classical roots, he would recuse himself from the conversation altogether. He would say something like, Look, I believe in the old ways of credentialing experts, and I have not, by those standards, become an expert myself. I’m really just an influencer with clout in the attention economy. So please allow me to apply to PhD programs and spend the next few years writing and successfully defending a dissertation on “The Classical Liberal Arts In The Twenty-First Century.” Maybe then I’ll be able to intelligently propose curriculum changes or precedent-setting educational policy.

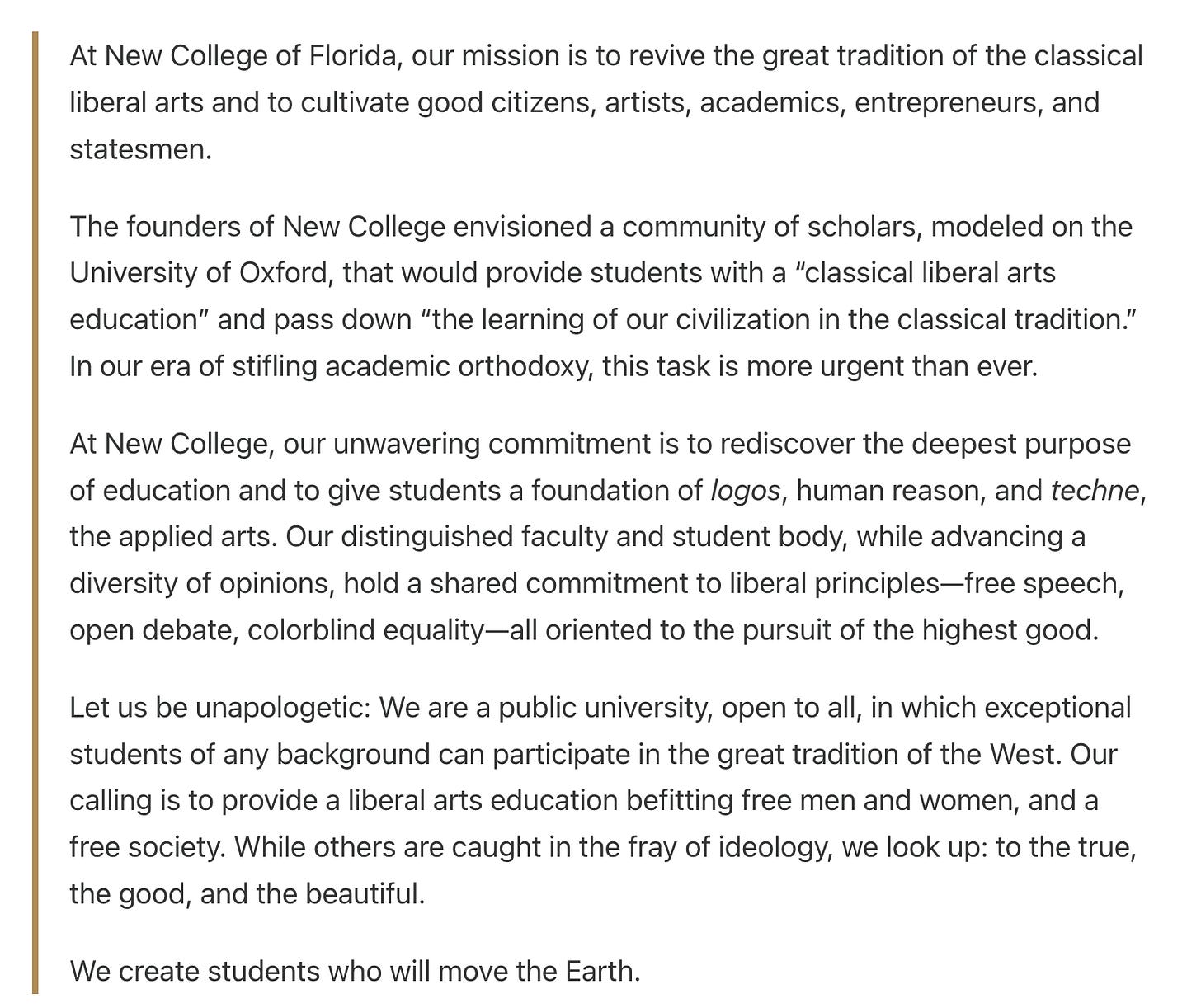

But of course Rufo has said no such thing. The closest he has come to articulating his vision for education is this draft of a mission statement for the New College of Florida. NCF was founded in the 1950s with an explicit commitment to what now would be cast as DEI principles. But in 2023 Florida governor Ron DeSantis assumed control of the school and remade its Board of Trustees in the image of Hillsdale College, a Christian college in Michigan. Rufo was one of those new Trustees. Unsurprisingly, NCF became the first American college or university to agree to the Trump Administration’s Compact For Academic Excellence In Higher Education, a set of conditions for receiving federal funding.

There’s a lot to unpack there, but let’s look at the draft Rufo published, because it’s the closest to a detailed proposal that he’s offered.

Not much of Rufo’s language has survived in the current version of New College’s mission statement. Perhaps that’s because he couldn’t resist activist tells like “in our era of stifling academic orthodoxy,” “while others are caught in the fray of ideology,” or “let us be unapologetic.” A mission statement shouldn’t be a slogan shouted through a bullhorn. It shouldn’t be limited to a political moment in time. It shouldn’t be reactive or defensive in tone.

But the takedown is all Rufo’s got. Everything else has been written in a thousand other mission statements. Logos and techne made the editorial cut, presumably because they sound classical. But that’s a little random. Why not throw a little more Latin in there, such as veritas for truth? Or pulchra for beautiful?

William Cronon’s essay “‘Only Connect’: The Goals of a Liberal Education,” articulates nearly everything you’ll find in NCF’s mission statement, only with more nuance and clarity. For instance, Cronon takes pains to point out that the artes liberales never had any explicit tie to political ideology. The “liber” in liberal simply means “free.”

The original artes liberales were only for the aristocracy. Over time, the word “free” came to describe more of humanity. That was the natural evolution of a tradition devoted to truth-seeking. In fact, one might say that steady progress toward diversity, inclusion, and equity is ineluctably linked to the classical liberal arts, since advances in all three have historically come from removing arbitrary barriers to education, therefore making it steadily more free.

So what is the “there” that Rufo is trying to reclaim? The core of his belief, on paper, seems much the same as the credo that Cronon laid down in the late 90s. Even back then Cronon joked about how defining liberal arts education meant choosing common requirements, which required making lists…exactly as the New College of Florida has done.

It’s like the idea of making America great “again.” Search for greatness in the past, and you’ll find that whatever it was, it is now logically tied to everything else that came after it. Heroize the pioneer, and you’ll have to accept that plowing up homesteads led to roads and to schools, which led to tractors and Big Tech, and every other modern thing. There was no standing still on the frontier. Idolize George Washington and John Adams, and you’ll have to contend with Thomas Jefferson and Benjamin Franklin and the fact that factions and opposites are closer to the truth of what America is than any pretense at unity.

The last line of the New College’s mission strikes as close to the heart of Rufo’s creed as anything: “Together, we seek the good, the true, and the beautiful, in the firm knowledge that only through the eternal verities can we move the earth.”

Ah, “firm knowledge” and “eternal verities.” I suspect we’re talking about Christianity, and by association Judaism. But are meant to ignore their fractious histories.

“Move the earth” is another curious phrase in both Rufo’s draft and the final copy. Does he mean Archimedes’ line (“Give me where [a place] to stand and I will move the Earth”)? And if so, isn’t the phrase self-defeating since Archimedes knew quite well that no physical place existed from which to work his famous lever? Mark Twain would have found the allusion comical since he saw limits to taking Archimedes at his word, even as hyperbole.

I asked Google where the phrase “move heaven and earth” originated, and it couldn’t tell me – sometime in the 18th century. ChatGPT hallucinated a quote from Philip Sidney’s “The Countess of Pembroke’s Arcadia” (1593) – turns out Sidney never used it. When I challenged Chat on that point, it apologized and hallucinated another answer, John Cowell’s The Interpreter (1607), which also proved to be unverifiable.

This would be an excellent research question, to which I don’t have a definitive answer. But I can say with confidence that “move the earth” has no meaning in Rufo’s use of the phrase. Either he’s referring to Archimedes, to an impossible hypothetical, or he’s alluding more vaguely to a source he can’t document — or to the Bible, where the only one moving heaven and earth is God. In which case wouldn’t the New College want to create students with more humility?

If Christopher Rufo really wants to restore classical education, let him cite his sources and explain what he means, because his language is Greek to me.

Curriculum

Curriculum proceeds from a credo. Accordingly, liberal arts education has always consisted of lists. Initially these were the trivium (grammar, logic, rhetoric) and the quadrivium (arithmetic, geometry, astronomy, and music). The reason that list didn’t remain static is simple: new disciplines emerged from the old, creating new hierarchies and taxonomies. A division like Natural Science didn’t exist until fairly recently, not to mention all the majors and subspecialties that have come to nest beneath that heading.

The same is true of literature. Many of the so-called Great Books borrowed from earlier periods and then went on to inspire the next generation of writers. That conversation is called “intertextuality.” You can’t understand Shakespeare without understanding the Bible, and you can’t understand Toni Morrison without understanding both. Writers like Morrison and Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie are particularly rich because they blend canonical texts with other cultural histories. There is no understanding Phillis Wheatley without understanding John Milton, and Wheatley sheds fresh light on Milton’s text, too, particularly his binary use of black and white imagery for moral themes.

Surely Rufo does not propose banning intertextuality?

I don’t have space to get fully into the weeds about academic history, so I’ll reiterate that this is why people get PhDs. You can’t Google your way toward a satisfactory explanation of how academic divisions emerged. You must study the primary texts, cobble together the story from disparate artifacts, and assemble all that into a logical form, such as the traditional scholarly monograph.

Take, for instance, A Diversity of Divisions: Tracing the History of the Demarcation between the Sciences and the Humanities, by Jeroen Bouterse and Bart Karstens. There is in fact an entire History of Science Society comprised of such experts. I’d love to hear their thoughts on what “classical liberal arts education” might mean. Probably dozens of different things.

But let’s look at the Gen Ed list at New College. That ought to tell us something about their priorities. I expected something a little more elaborate, a little more “great,” to use their own language. But this is it:

The state of Florida requires all college students to complete 36 credit hours of approved general education coursework. This includes state-mandated core courses distributed across five content areas. Students at NCF must take one course (4 credits) from each of four content areas (Communications, Mathematics, Natural Science, Social Science/Civic Literacy) as well as a specially designed Humanities course on Homer’s Odyssey (2 credits). NCF students round out their general education requirements by selecting an additional four offerings from our distinctive Enduring Human Questions (EHQ) seminars (16 credits) and participating in a unique 2 credit course, Introduction to Techne.

Even in the nineteenth century, a “classical” education meant required study of Greek and Latin. There’s a little of that plopped in by way of Homer’s Odyssey, but assuredly that is read in translation, which is not at all the same thing.

The only salient differences here, from the thousands of Gen Ed lists in the U.S., are the Homer course, four Enduring Human Questions seminars, and a techne offering.

The upshot is a vague nostalgia for Great Books with little understanding of how those influential texts were produced by hybridity. Great scholars did not limit themselves to a Western or Eastern binary. Karen Armstrong shows in her A History of God that world religions cross-pollinated each other initially. There’s no easy way to set Greek philosophy apart from Falsafa, the Islamic tradition of philosophy, which went on to shape the West through Latin translations. Thomas Aquinas not only synthesized Christian theology with Aristotelian philosophy, he frequently cited Muslim thinkers like Al-Ghazali. Even Europe, which conservatives have in mind whenever they speak of the “good” and the “beautiful,” is filled with this commingled history in art, architecture, and cuisine.

There is no button for rewinding to a pure origin of anything. Even if there were, to what era might Rufo and his entourage aim their time machine? The early 1900s? The 1800s? Surely not the Enlightenment or alchemy-addled Middle Ages. Surely not ancient Greek academies, which met outdoors and had no course lists or degrees.

Even wokeism, Rufo’s favorite target, isn’t limited to recent history. It has its didactic origin in Puritan New England and before that in the persecution the English dissenters fled and before that in the Inquisition and every other form of religious tyranny.

I would need many more essays to propose my own vision for rebuilding higher ed. But mostly I think that Cronon got it right: the liberal arts aren’t static. Being educated isn’t a “state,” it’s a perpetual way of being.

To be liberally educated is to remain curious about hybridity: the past, present, and future intersections of things. One way to identify someone who is not intellectually free is to listen to them wax territorial about imagined histories.

Most of my content in 2025 is free, but monthly installments of my memoir-in-progress are only available to full members. For access, or just to support quality writing, please consider upgrading your subscription. I’m also proud to be a Give Back Stack. 5% of my earnings in Q4 will go to Centre County PAWS, a no-kill shelter focusing on adoption, education, and community assistance.

See my accountability page, with receipts for Q1, Q2, and Q3 here.

I think move the earth or a phrase close to it was in a Dodge commercial a while back.

This is a thoroughgoingly excellent review of what I agree is an entirely expected political move, and one which like yourself, I am placed in a somewhat liminal position regarding. I do think this will, or should, become a reference piece on topic. My version is contained in the following:

https://www.amazon.com/dp/1682358488

When imported staffers purged the FNS library of some 4000 titles, I did wish to have been there to collect them for my own! But that moment was for me the beginning of a new regime of narrowing curricula to the point of it becoming irrelevant. How many steps between the landfill and Fahrenheit 451; riddle me this.