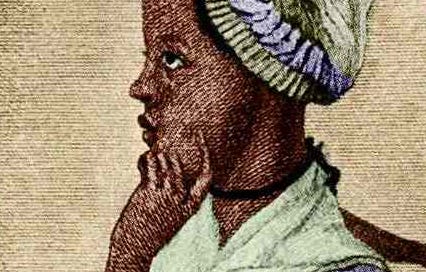

Phillis Wheatley was kidnapped in Africa, brought to New England on a slave ship, and purchased by a wealthy Boston family in 1761. She had just lost her two front teeth, which likely meant she was seven years old. She wrote her first poems in English four years later and was soon published in a regional newspaper. Wheatley’s elegy for George Whitefield, which drew international attention in 1770, was her first major breakthrough. By that time she had gathered enough poems for a manuscript, but she could not find an American publisher. In 1773, Wheatley delivered her book to Archibald Bell, a London publisher, who distributed a successful first edition later that year.1

Phillis Wheatley was 20 years old when the world knew her name. She is an American genius. But chances are good that you have never heard of her.

Today I return to my series on American authors who most people would never know without a traditional literature survey. This series is a reminder of what we lose in national identity and civic engagement when we push the humanities aside. To start at the beginning, read my introductions to Anne Bradstreet and J. Hector St. Jean de Crévecoeur.

A master class in double voicing

Wheatley’s most widely anthologized work is “On Being Brought from Africa to America.” The poem offers a series of contrasts and associations that the reader must resolve for themselves. Just as Anne Bradstreet placated Puritan patriarchs with one voice while undermining them with another, Wheatley delivers an elusive message that lands differently now than it did with her largely white audience in 1773.

Here is the original. If you a prefer a study text, try Ann Woodlief’s version.

On Being Brought from Africa to America

'Twas mercy brought me from my Pagan land, Taught my benighted soul to understand That there's a God, that there's a Saviour too: Once I redemption neither sought nor knew. Some view our sable race with scornful eye, "Their colour is a diabolic die." Remember, Christians, Negros, black as Cain, May be refin'd, and join th' angelic train.

“On Being Brought” reminds me of a Thanksgiving dinner that I shared with extended family in Georgia. That side of the family is conservative, and I often had to bite my tongue during meals. The Civil War was “The War of Northern Aggression” – that kind of thing. One of my second cousins made the same specious claim that Ron DeSantis has recently tried to resurrect: that some Black people benefited from slavery.

Wheatley’s poem is powerful because it invokes that racist premise in the first four lines, suggesting that her forced removal from Africa might have been merciful because it saved her soul. But “mercy” is a euphemism for providence, not for her captors. In that sense, Wheatley positions herself as the beneficiary of divine grace, not of human compassion.

In fact, the second half of the poem works directly against the idea that Wheatley benefited from enslavement. By the poem’s end, she is the teacher, not the one being taught.

The most crucial line is the penultimate one. “Remember” squarely situates Wheatley in the minister’s role — you can almost see her at the pulpit. The punctuation of the line is also crucial to its meaning. If the commas after “Negros” and “Cain” were removed (as they were in some American versions of the poem), the line would merely echo the bigoted claim before it, reminding Christians that even people of color might be redeemed.

But that is not what Wheatley’s text says. “Christians” and “Negros” are equally subordinated by commas to the spiritual imperative, “Remember.” The allusion to Cain also replaces the racist association of skin color and salvation with the universal condition of original sin.2 So the line, as I read it, says that everyone stands in equal need of redemption.

Can one read Wheatley’s “angelic train” as anything other than an inclusive band of refined human beings?

Cornelius Eady says this all better:

I also find Paula Bennett’s analysis moving:

“Trying neither to evade the consequences of her racialized difference nor to hide behind European literary conventions, Wheatley placed at the center of her work the tensions and possibilities her difference produced… She wanted to be acknowledged, even in her difference, as a legitimate member of the society in which she lived. This desire to participate as an African and as a poet in colonial culture was the complex, self-contradictory project of her verse.”

Wheatley’s poem endures because it is not limited to the Black experience. “On Being Brought from Africa to America” speaks to the isolation that many first-generation students feel in college and as professionals, especially those from immigrant families. There are echoes of Wheatley in works as varied as Richard Rodriguez’s Hunger of Memory, Kao Kalia Yang’s The Latehomecomer, and Tara Westover’s Educated.

Sometimes it feels like mercy to leave poverty or a provincial life to join the community of arts and letters. Fill in the blank: “Once I ____ neither sought nor knew.” But it is also misery to know that talent and desire are no guarantees of belonging.

The embrace of reason and love

I am an unashamed Romantic. Even my prose defaults to lyricism. I want my words to taste sweet, to rise above the cold potatoes of rationality. And yet I am also a student of the Enlightenment, the era in which Wheatley rose to fame, and I recognize that her verse turns on tight logic. Throw a syllogism at Wheatley, and her poems will hold up.

No poem illustrates Wheatley’s balance of reason and feeling better than “Thoughts on the Works of Providence.” I have to keep reminding myself that she was a teenager when she wrote it.

Wheatley’s God is “the monarch of the earth and skies.” Her early stanzas echo Thomas Paine’s notion that instead of reading the Bible, people would be better off reading “the Scripture called the Creation.”

In one of Anne Bradstreet’s poems, Spirit claims that heavenly matters are too lofty for her lowly sister, Flesh. But Wheatley sees the physical world as heavenly in its own right: “Almighty, in these wond'rous works of thine, / What Pow'r, what Wisdom, and what Goodness shine!”

Wheatley echoes the Enlightenment trope of God as a prime mover or blind watchmaker, and much of her language is scientific – “vast machine”; “solar ray”; “heat and light.” But her verse also bubbles over with joy. The sun is not an indifferent orb — he is Phoebus, light personified.

Phoebus makes Creation smile. Shouldn’t we all greet the sunrise with this kind of hope? “Hail, smiling morn, that from the orient main / Ascending dost adorn the heav'nly plain!”

You don’t have to be a Christian to admire the marriage of concept and form in Wheatley’s verse. Rhyme and meter enhance the message in the following passage. Maybe it’s a stretch to say that the final line anticipates hip-hop, but if rap and jazz are fusions of European and African influences, then surely we hear something like that in Wheatley’s voice.

How merciful our God who thus imparts O'erflowing tides of joy to human hearts, When wants and woes might be our righteous lot, Our God forgetting, by our God forgot!

(By the way, have you ever tried to write in iambic pentameter without those ten beats and rhyming couplets feeling forced? It is damn hard. Wheatley makes it look easy. No filler words in there. No froth or slack in the ideas.)

But my favorite part of the poem alludes to a debate among the “mental pow’rs” about who most faithfully illuminates “th’ Eternal.” What might have been a standoff between Reason and Love, perhaps an homage to Bradstreet’s feud between Flesh and Spirit, turns into a familial embrace. Love defends her divine origins — heaven and earth would never have been created without her. But Love also entreats Reason to end “this most causeless strife.”

In a delicious twist of wit, Love convinces Reason. “Thy words persuade,” Reason cries. “[M]y soul enraptur'd feels / Resistless beauty which thy smile reveals.” Then, so moved by her own words, Reason pulls Love into her arms. Take that, Descartes.

Wheatley’s closing stanza shows how unnecessary it is to pit the mind against the heart. In fact, I see these lines as a perfect distillation of what the liberal arts try to teach: a sense of wonder and curiosity about the world, an abiding affection for people and for the places we inhabit, and a sense of duty to the collective good.

Infinite Love where'er we turn our eyes Appears: this ev'ry creature's wants supplies; This most is heard in Nature's constant voice, This makes the morn, and this the eve rejoice; This bids the fost'ring rains and dews descend To nourish all, to serve one gen'ral end, The good of man: yet man ungrateful pays But little homage, and but little praise. To him, whose works arry'd with mercy shine, What songs should rise, how constant, how divine!

Only the good die young

I wish there were a happy ending to Phillis Wheatley’s story. She did not die a slave — the Wheatleys granted her freedom after pressure from English readers, who couldn’t understand how a family could continue to own one of the great poets of the time (and, by the way, what’s all this talk about freedom from England while slavery persists?!). If you’ve been thinking that the Wheatleys weren’t so bad because they gave Phillis a great education and pulled whatever strings they could to get her published, you might think again knowing that they basically left her to fend for herself as a free woman.

Any young woman of the time, even the most privileged, would have struggled to maintain financial independence at age 20 if cut off cold turkey from family support. Wheatley did her best to market her own book, but the timing was bad. The British took Boston the year after Poems on Various Subjects was published, and people had more pressing concerns than book buying for the next several years.

As Henry Louis Gates, Jr. observes, Wheatley did her best to leverage powerful connections, writing directly to George Washington and enclosing a flattering poem about him that he later had published (though he agonized about indulging his vanity in that way). But her famous friends did little to help her, and she eventually married John Peters, a grocer who struggled to make ends meet.

It is hard to overstate Phillis Peters’ suffering as a young mother. She lost her first two children when they were still babies, and she was weighed down by her husband’s debts. Despite all this heartache, she continued to write and even finished a second book in 1779, which she tried to publish for the next five years. But publishers ignored her. In December, 1784, overworked as a scullery maid, Phillis died of pneumonia while John languished in a debtors’ prison. She was 31 years old. Her sick baby died the same day.

There has been some debate about whether John Peters exploited Phillis or whether they knew true love. For instance, when he kept trying to publish her second book after her death, was he just trying to cash in on her talent, or did he hope to finish what she had left undone? Honorée Fanonne Jeffers tells a more sympathetic story about Peters in The Age of Phillis, imaginatively reconstructing the life of the young poet and challenging earlier biographies. New archival materials also suggest that the poet most Americanists know as Phillis Wheatley ought to be remembered as Phillis Wheatley Peters — and that John Peters supported her vocation.

But there is no brightsiding the fact that her second book was lost and has never been found. Phillis Peters died unnecessarily — not of pneumonia but of poverty, of systemic barriers that even a woman of her prodigious talents could not overcome.

She died just one year after American independence had been won.

Sometimes I wonder how many geniuses have been lost to violence, hatred, or squalor. Einstein had equals in Auschwitz and Dachau — talent abounded at Terezín. How many prodigies were snuffed out in Rwanda, in the Native American Holocaust? How many potentially great minds have been lost in Gaza, Israel, Afghanistan, or Iraq?

The ethicist in me balks at genius as a measure of worth. Other Black people died in poverty, coughing the bitter irony of freedom without justice, and many white colonists fell before their time — to fever, to hunger, to a British bayonet. The fact that we don’t know their names does not mean their lives meant little.

But the poet, as Emerson says, is representative. The poet “stands among partial men for the complete man, and apprises us not of [her] wealth, but of the commonwealth.” We revere a genius, Emerson says, because they are more ourselves than we are. “They receive of the soul as [we] also [receive], but they more.”

I love Phillis Wheatley’s poetry not merely for its mastery, though I stand in awe of that, too. I love it because it does what great literature should do: it reveals me to myself. Wheatley is a reminder that branding and SEO and all the hallmarks of success in our time are but shadows and dust. What she achieved will outlast all that.

I wish for her own sake that Phillis Wheatley Peters had lived a longer and happier life. A selfish part of me also wishes that I had more of her poems to read. I’d like to have seen what those poems might have unlocked — perhaps something I didn’t even know I held within me. That loss is also America’s loss.

The least we can do is remember the great gift of art that she left us. For a time, that is what teaching American literature allowed me to do. Thank you for helping me honor her in some small way here.

Learn a little more about Phillis Wheatley:

As Wheatley’s fame rose, suspicion of her authenticity did, too. She faced something like a plagiarism tribunal in 1772, when eighteen leading intellectuals gathered in Boston to quiz her about her manuscript. Henry Louis Gates, Jr. captures the scene.

There’s no record of what was said, but Wheatley convinced the group that she was legit. Although no American publisher would take her book, Phillis’s answers to the Boston panel secured the following letter, signed by those 18 ministers, thinkers, and politicians, which the Wheatley family carried with them to London.

“As it has been repeatedly suggested to the Publisher, by Persons, who have seen the Manuscript, that Numbers would be ready to suspect they were not really the Writings of PHILLIS, he has procured the following Attestation, from the most respectable Characters in Boston, that none might have the least Ground for disputing their Original.

We whose Names are under-written, do assure the World, that the POEMS specified in the following Page, were (as we verily believe) written by PHILLIS, a young Negro Girl, who was but a few Years since, brought an uncultivated Barbarian from Africa, and has ever since been, and now is, under the Disadvantage of serving as a Slave in a Family in this Town. She has been examined by some of the best Judges, and is thought qualified to write them.”

Referring to sin as “black” might seem to make the same error, and I concede that the figurative associations with white (positive) and black (negative) remain problematic. However, the distinction is Wheatley’s, and it remains significant. It is one thing to literally associate people with the devil because of their color. It is quite another to invoke a spiritual metaphor that implicates all equally. Wheatley’s double voice hinges on the difference.

Thanks Josh for introducing us to Wheatley.

"Our god forgetting, by our god forgot" has the ring of Shakespearean rhythm to me. But I agree it could also be a line in Hamilton.

Beautiful.