This was the road over which Ántonia and I came on that night when we got off the train at Black Hawk and were bedded down in the straw, wondering children, being taken we knew not whither. I had only to close my eyes to hear the rumbling of the wagons in the dark, and to be again overcome by that obliterating strangeness. The feelings of that night were so near that I could reach out and touch them with my hand. I had the sense of coming home to myself, and of having found out what a little circle man's experience is. For Ántonia and for me, this had been the road of Destiny; had taken us to those early accidents of fortune which predetermined for us all that we can ever be. Now I understood that the same road was to bring us together again. Whatever we had missed, we possessed together the precious, the incommunicable past.

One of my great pleasures as a professor was taking my students to Willa Cather’s hometown: Red Cloud, Nebraska. Cather’s settings and characters are remarkably faithful to their real-life prototypes, and so my students often felt, after spending a semester studying Cather’s novels, that Red Cloud had become an imaginative home.

The familiarity that Jim Burden describes in Book V when he accompanies the Cuzak boys on their chores is very similar to what a reader feels while walking the streets in Red Cloud or the farms beyond the edge of town, because we’ve been there before.

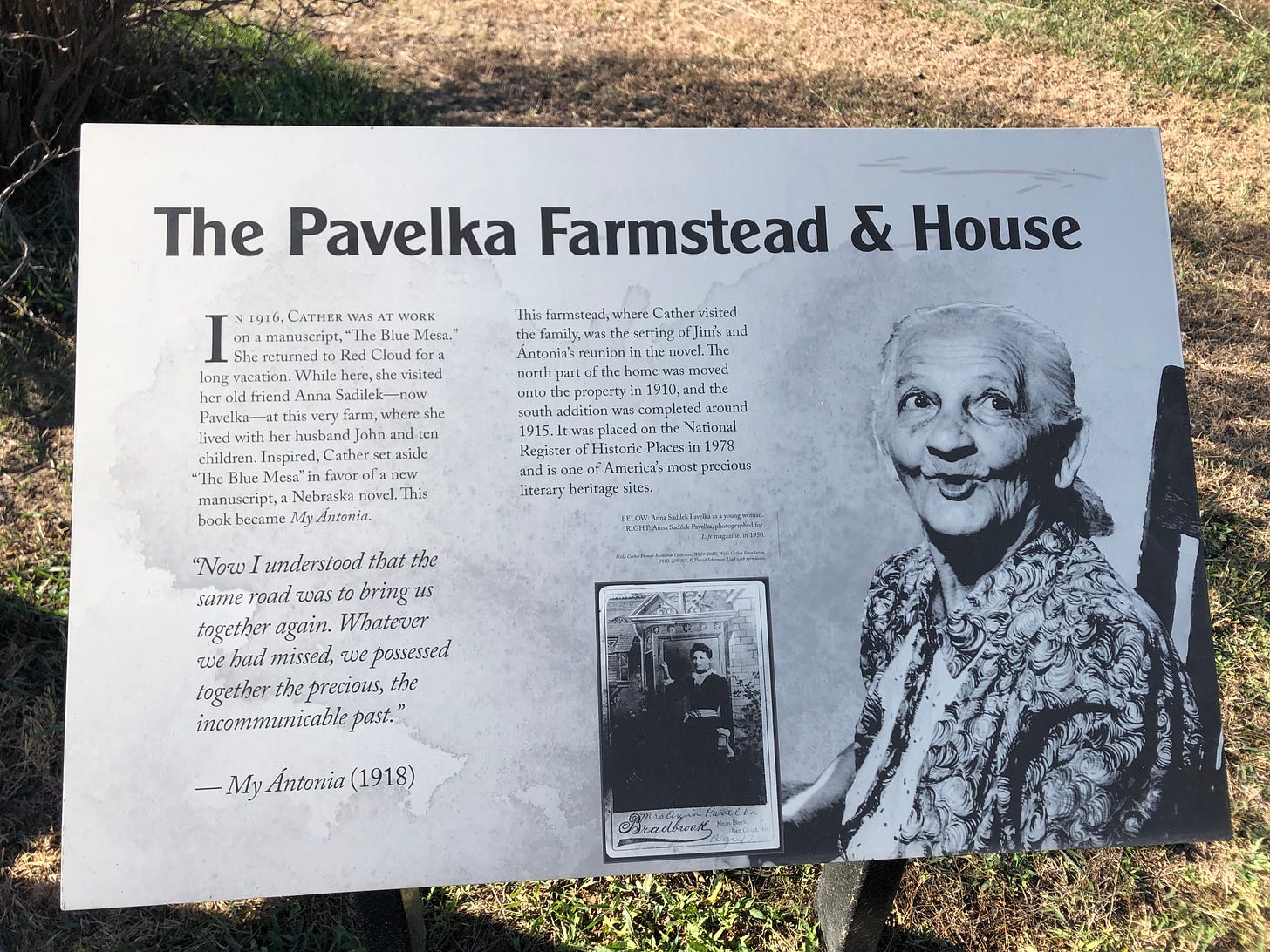

As Jim says, “It seemed, after all, so natural to be walking along a barbed-wire fence beside the sunset, toward a red pond, and to see my shadow moving along at my right, over the close-cropped grass.” Just so, visiting sites like the Pavelka Farmstead, which Cather reimagines as the Cuzak farm, made my students smile with recognition. For some it was more emotional.

Red Cloud is the largest living memorial to any American author. This is partly because Cather sets so many of her stories there and also because the once bustling railroad town became a backwater in the mid-twentieth century. Many of the properties that have now been restored were acquired for next to nothing and have been brought back to life through generous donor support.

When I first visited the Pavelka Farmstead in 1997, while taking Sue Rosowki’s graduate seminar on Cather, it was a wreck. And it stayed that way for the next twenty years. Only recently has it been restored, and the film below captures some of the difficult choices that go into that kind of curation.

For instance, should the entire floor be replaced, or should some of the damage be preserved for authenticity?1

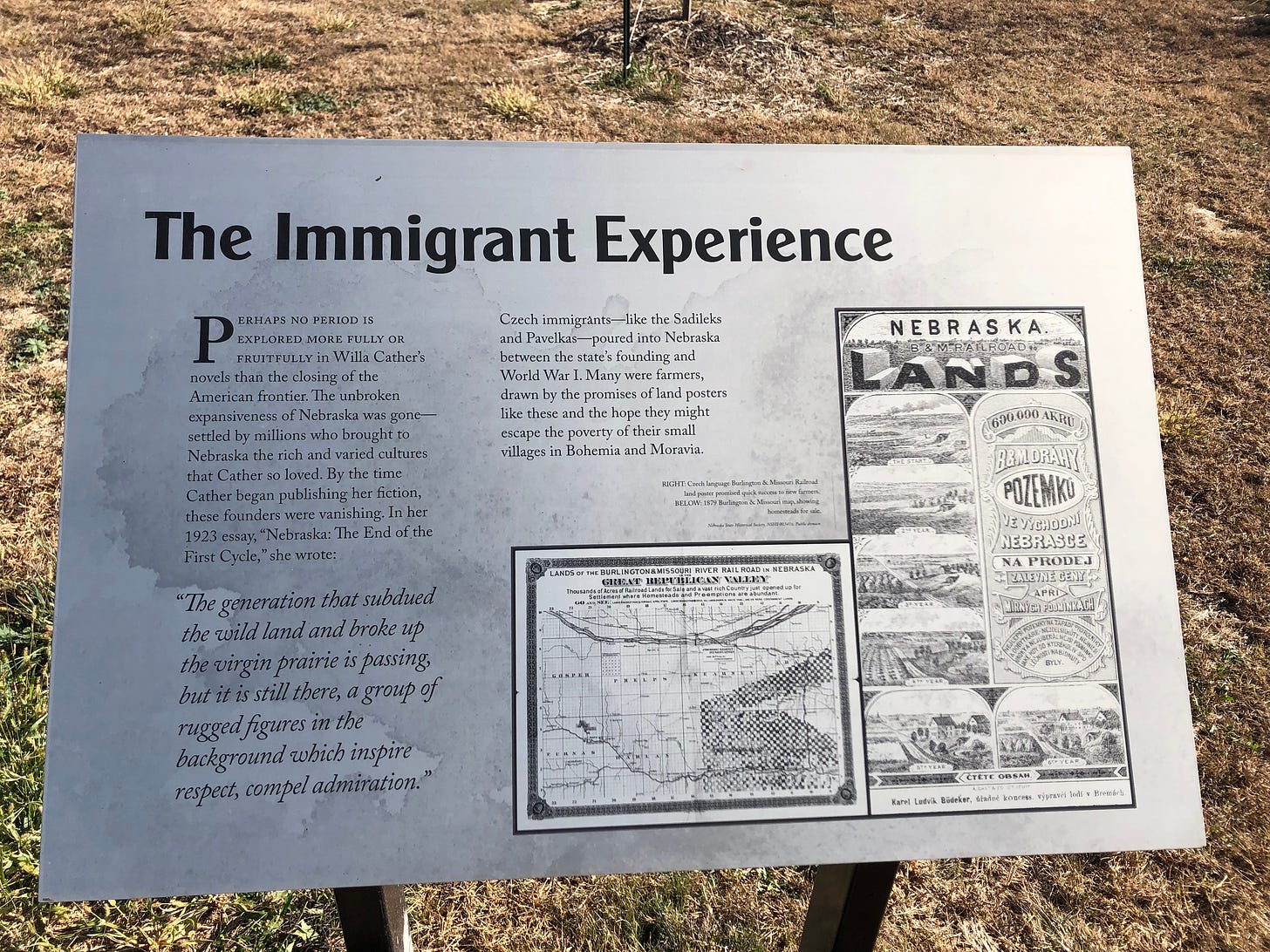

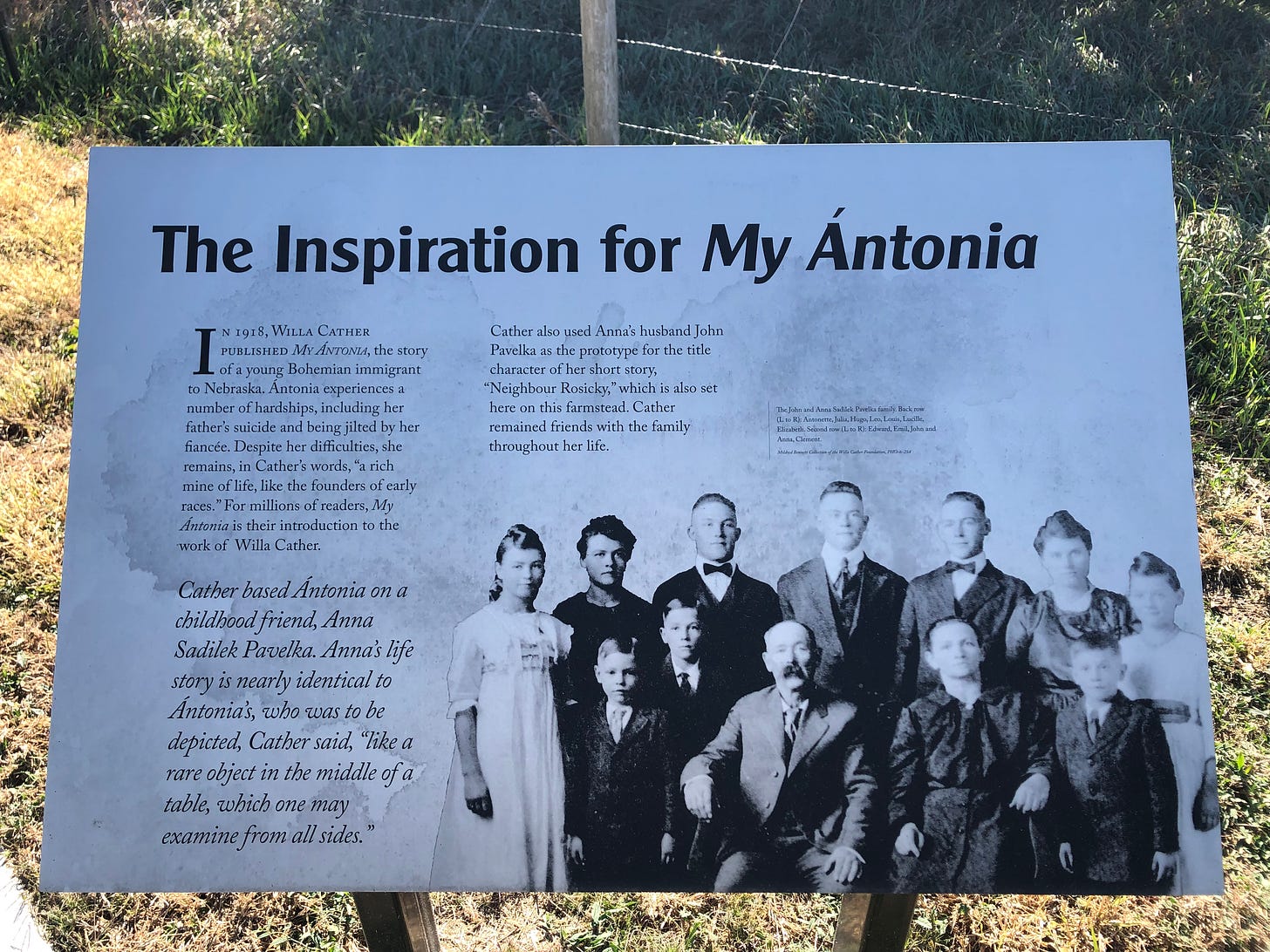

There are now many rich interpretive materials at Red Cloud sites, including these near the Pavelka home.

When I first began this read along, I imagined that it might scale nicely onto a yearlong project, since Cather published exactly 12 novels. Reading one novel a month would be accessible enough. And how marvelous it would be to cap that conversation with a group tour of the Cather Archive in Lincoln and the many historic sites in Red Cloud, as I once did with my juniors and seniors! A man can dream.

Perhaps if you didn’t see my earlier poll, you’ll take a moment to complete it now? I’d love to hear if you would sign up for the yearlong project if I offered it and whether you might be interested in the group activities as a finale.

Now I’d love to hear how Book V speaks to you. I offer a few questions below for each chapter. But I’d also love to hear your independent impressions. And, since this is our final discussion of My Ántonia, please feel free to comment on the novel as a whole.

Book V

Chapter 1

There is a curious logic to Jim’s statement that “Some memories are realities, and are better than anything that can ever happen to one again.” Do you agree? I’m highlighting it because just two sentences prior, Jim acknowledges that growing up requires us to part with many illusions. Is he trying to hold onto rose-tinted memories or actual realities?

My friend Steve Shively often compares the description of Samson d’Arnault to that of Ántonia’s son, Leo, with his wooly, lamblike, hair. The Russian bachelor Peter also has these qualities. What do you make of the lion/lamb juxtaposition in Leo’s name and description? Of his similarity to Blind d’Arnault and Peter? What does it add to the narrative, if anything, that Leo is an Easter baby?

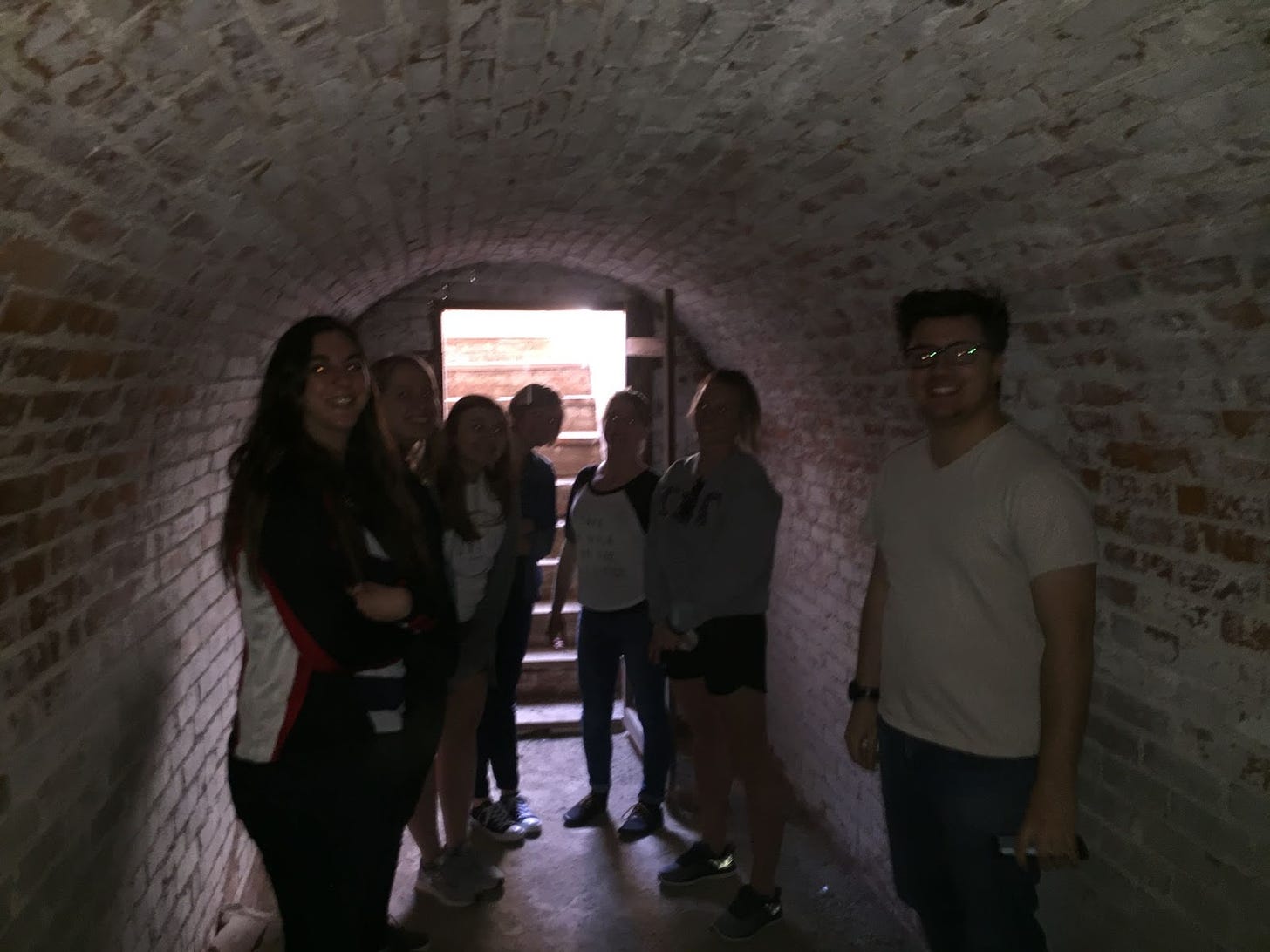

One of the famous passages from this chapter is Jim’s visit to Ántonia’s fruit cellar, a womb-like space from which her children burst onto the prairie:

We turned to leave the cave; Ántonia and I went up the stairs first, and the children waited. We were standing outside talking, when they all came running up the steps together, big and little, tow heads and gold heads and brown, and flashing little naked legs; a veritable explosion of life out of the dark cave into the sunlight. It made me dizzy for a moment.

This is one of the sites that I loved to share with my students. You can see us here, standing comfortably in the cellar and walking back up into the light.

Jim and Ántonia retire to an orchard to continue their conversation. This is one of many outdoor sanctuaries that offer them intimacy. As with many similar settings in Cather’s fiction, this is a place defined both by freedom and safety, limitlessness and shelter, rather like an embrace. You can feel that depth in the language, can’t you?

There was the deepest peace in that orchard. It was surrounded by a triple enclosure; the wire fence, then the hedge of thorny locusts, then the mulberry hedge which kept out the hot winds of summer and held fast to the protecting snows of winter. The hedges were so tall that we could see nothing but the blue sky above them, neither the barn roof nor the windmill. The afternoon sun poured down on us through the drying grape leaves. The orchard seemed full of sun, like a cup, and we could smell the ripe apples on the trees. The crabs hung on the branches as thick as beads on a string, purple-red, with a thin silvery glaze over them.

I don’t have adequate space here to explain how masterful the nuances are in this chapter. Cather keeps circling back to the past in the familiarity that Jim feels in seeing his shadow, sleeping in the barn with the boys, the stories familiar to us (like the rattlesnake) that have now matured into legends. In all these ways, the story feels like it’s coming home, tugging on old threads, resolving conflicts, returning us to the root chord of the song.

I’ll linger just a moment over a sentence that ought to give us chills, given its setting and the brutal scene it recalls, but that feels cleansed by this stage of the narrative:

The boys told me to choose my own place in the haymow, and I lay down before a big window, left open in warm weather, that looked out into the stars. Ambrosch and Leo cuddled up in a hay-cave, back under the eaves, and lay giggling and whispering. They tickled each other and tossed and tumbled in the hay; and then, all at once, as if they had been shot, they were still.

This is not garden-variety nostalgia, is it? The pain from Mr. Shimerda’s suicide is still real, the past is still close at hand, even as time has moved inexorably forward.

Cather’s ability to evoke these feelings is thoroughly elusive from a craft standpoint. If you have never belonged to a place, never rooted yourself within it and suffered prolonged separation from it, I suppose My Ántonia will not achieve its maximum effect. But I’m aware, as I read these lines, of their ability to awaken my own memories, the parts of my own past that are still within reach every time I return to Montana.

Jill Swenson suggested last week that Cather’s representation of Ántonia was heroic, in the classical sense, and we can hear some of Jim’s myth-making here. Only I wonder whether, by seeing her in this way, Jim is reinforcing conventional tropes about women as angels, lifting Ántonia onto a false pedestal of motherhood, or honoring her domesticity in the light it deserves?

She lent herself to immemorial human attitudes which we recognize by instinct as universal and true. I had not been mistaken. She was a battered woman now, not a lovely girl; but she still had that something which fires the imagination, could still stop one's breath for a moment by a look or gesture that somehow revealed the meaning in common things. She had only to stand in the orchard, to put her hand on a little crab tree and look up at the apples, to make you feel the goodness of planting and tending and harvesting at last. All the strong things of her heart came out in her body, that had been so tireless in serving generous emotions.

It was no wonder that her sons stood tall and straight. She was a rich mine of life, like the founders of early races.

Chapter 2

It is curious that this chapter is titled “Cuzak’s Boys,” given that it is mostly about Jim’s reunion with Ántonia – and that we don’t meet Cuzak himself until the second chapter. What do you make of his character? Of his relationship with Ántonia?

Cather treats us to another story within a story, with the secondhand account (thirdhand, through Jim to us) of Mrs. Cutter’s murder. This is a curious flourish, another tug on an old thread. What does it add to the ending? What do you notice about how this story is retold?

We also get Cuzak’s back story, summarized and reconstructed by Jim. What catches your eye in this history of a relatively minor character? Why give Cuzak himself this much ink in a story about Ántonia?

Chapter 3

Jim’s disappointment in town, and his escape into the wilder land in the countryside, is also possible to recreate with students. Red Cloud proper is a quiet, rundown place. The National Willa Cather Center is one of the few economic engines of the community. I’d often take my students on the town tour, visiting the Harling House and Cather’s childhood home. We typically rented the Cather family’s second home, which is now an Airbnb with each bedroom charmingly named for a town in Cather’s fiction (yes, you can sleep in the Black Hawk suite).

But a visit to Red Cloud is not complete without a walk on the Memorial Prairie, an acreage south of town that has supported livestock over the years, but has never been plowed. This is the place to ponder Jim’s final lines:

…this half-mile or so within the pasture fence was all that was left of that old road which used to run like a wild thing across the open prairie, clinging to the high places and circling and doubling like a rabbit before the hounds. On the level land the tracks had almost disappeared—were mere shadings in the grass, and a stranger would not have noticed them. But wherever the road had crossed a draw, it was easy to find. The rains had made channels of the wheel-ruts and washed them so deep that the sod had never healed over them. They looked like gashes torn by a grizzly's claws, on the slopes where the farm wagons used to lurch up out of the hollows with a pull that brought curling muscles on the smooth hips of the horses. I sat down and watched the haystacks turn rosy in the slanting sunlight.

You can also take a virtual tour of the Memorial Prairie here:

Well, we’ve done it! It’s been a joy to share these Fridays with you. Next Friday I’ll share a page where the entire My Ántonia read along will live henceforth, so other readers can follow our tracks asynchronously. Thanks to everyone who has made this experiment such a delight, including

, , , , , , , , , and many others who enriched the discussion each week.These choices are not unlike my recent post on how memoirists try to strike an honest pose as the narrators of their own lives.

Joshua - I’ve loved this. I’m sorry I got behind - we moved last weekend and it’s been solid packing, moving, unpacking and organizing. Today, I’m off to co-lead a weekend retreat, but I *will* catch up! Really appreciate all that you put into this. I’ve learned so much.

one correction to my comment "more Bergman and less Capra" I was thinking of the film, The Emigrants, with Liv Ullman. But it wasn't directed by Bergman but by Jan Troell! A powerful film that depicts the life of European emigrants at the turn of the century.