Start With A Riddle, Not A Rationale

What do cinnamon, Stephen Jay Gould, and Kleenex all have in common?

I could tell you, but I’m not going to. Not yet.

That, in miniature, is how a good essay hooks a reader: with a puzzle to solve. But instead of preaching that point, let me try to prove it to you.

One of the great pleasures of graduate school was browsing local bookstores. Amazon was making a name for itself as an online retailer then, but nobody I knew bought their books that way because we all lived within walking distance of downtown, where we had several excellent booksellers to choose from, including the university.

My mindset followed Kurt Vonnegut’s famous anecdote about buying an envelope. He tells his wife he’s going out to the post office, and she asks him why he doesn’t stock up on mailing supplies to save himself the trouble. He explains that he likes all the surprise encounters, the fire engine suddenly whizzing by, and he gets more out of this than he does from the errand itself.

Here’s Vonnegut:

The moral of the story is — we’re here on Earth to fart around. And, of course, the computers will do us out of that. And what the computer people don’t realize, or they don’t care, is we’re dancing animals. You know, we love to move around. And it’s like we’re not supposed to dance at all anymore.

That’s why I walked downtown to shop for books. It was one way to escape the library stacks, to get out of my head, dance a little. Convenience was never the point.

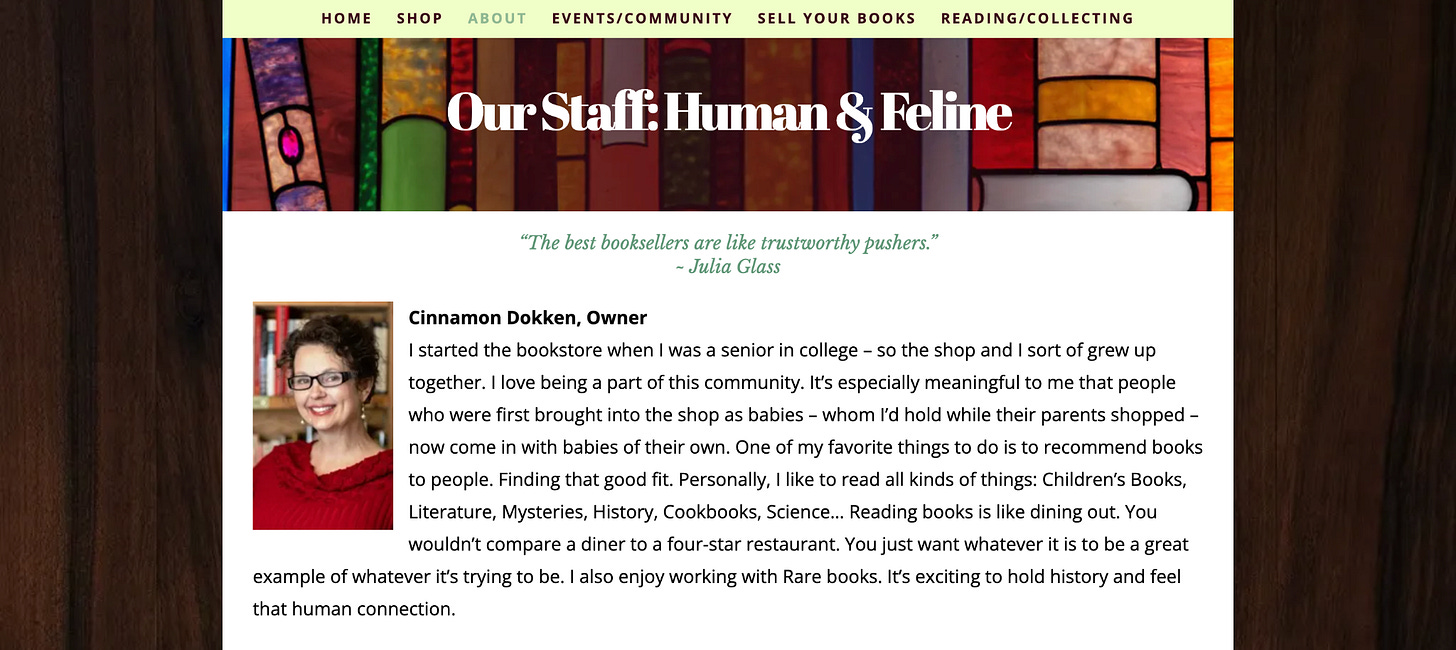

I bought a lot of used books at A Novel Idea, a clever name surpassed only by the owner, one Cinnamon Dokken. Cinnamon owned a half dozen cats who napped in the store windows and never refused a scratch behind the ears. It must have been the oak flooring and shelves that made her shop glow, or maybe the fact that the storefront faced west and caught the afternoon sun. In my memory, those stacks are always bathed in light.

It gave me a little surge of happiness today to discover that both the shop and Cinnamon are still going strong.1

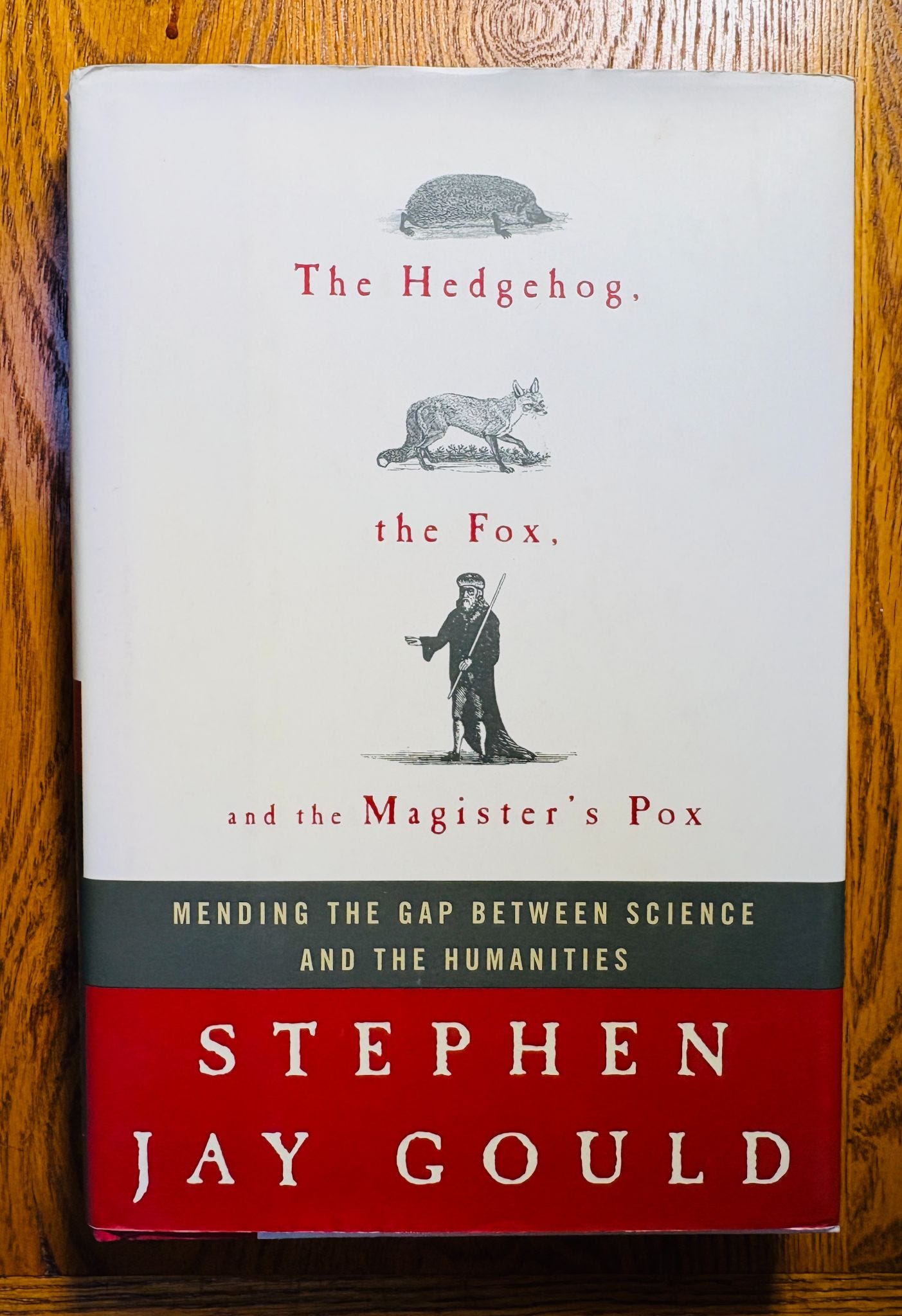

Cinnamon also sold new releases, and browsing her stock was one way I stayed up to date with the latest in science writing. It’s where I discovered Atul Gawande’s Complications, E.O. Wilson’s The Future of Life, and Stephen Jay Gould’s The Hedgehog, the Fox, and the Magister’s Pox.

Gould filled a lot of lecture halls, and I’m sorry I missed the chance to listen to him live. But I read a lot of his essays, and I loved how the titles were always perplexing.

Here are three from The Flamingo’s Smile: Reflections in Natural History (1987):

“Adam’s Navel”

“Of Wasps and WASPS”

“Only His Wings Remained”

Now it turns out that Adam’s navel (or lack of one) is one way of thinking about evolution. But Gould doesn’t frontload a thesis, he dances a little first.

The ample fig leaf served our artistic forefathers well as a botanical shield against indecent exposure for Adam and Eve, our naked parents in the primeval bliss and innocence of Eden. Yet, in many ancient paintings, foliage hides more than Adam’s genitalia; a wandering vine covers his navel as well. If modesty enjoined the genital shroud, a very different motive – mystery – placed a plant over his belly. In a theological debate more portentous than the old argument about angels on pinheads, many earnest people of faith had wondered whether Adam had a navel.2

In “Of Wasps and WASPS,” Gould muses on the cruelty that we attribute to predatory insects while remaining blind to the brutality of colonialism. And “Only His Wings Remained” alludes to the grisly aftermath of mantid mating. But in each of these cases we’re invited into a riddle, not a rationale.

Who is “he,” why does he have wings, and why is that all that’s left of him? I, for one, want to know.

The Hedgehog, the Fox, and the Magister’s Pox is another such riddle. We know the three relate in some way, and that intrigue draws us into the book, where we find Gould’s passionate call for harmony between the sciences and the humanities, including the acronym NOMA, which stands for non-overlapping magisteria. The magisterium of science asks “how,” and the magisterium of literature, religion, philosophy, history, and art asks “why,” and there is no need for either to claim sovereignty over the other.

But before we get into all that we need a little suspense, a little playfulness, a wink that assures us that we’ll dance a little before we get to the point.

Ben Percy illustrates the idea in a chapter on urgency in Thrill Me. His friend Darren asks him, when they first meet in high school, “How do you make a tissue dance?” It’s the first half of a joke, but Darren didn’t know that. He heard it from a stranger at an amusement park, but was whisked away by a roller coaster before the answer came.

This was long before you could just ask Google or Siri, so Darren sincerely didn’t know, and neither did Percy. A few years later, Percy overheard the full joke at the gym where he worked, but he refused to tell Darren the punch line for months. It wasn’t until the summer after graduation, when the two were waterskiing, that Percy finally spilled the beans, and it was so disappointing that Darren dropped the tow rope and sank briefly into the lake.

How do you make a tissue dance?

You put a little boogie in it.

It’s a letdown, Percy explains, because “desire is the most thrilling and pleasurable and terrifying condition. Anticipation satisfies us in a way acquisition does not.”

That’s why the cold open is ubiquitous in streaming TV, why you can guarantee that the first scene will be a catastrophe that peaks just before the first ad break. It’s also why spoilers are so rude.

Desire is even more essential at the top of an essay, where you know you’re in for some exposition eventually and need a little urgency to spice up the deep thinking. A cold open can work there, too, but Gould shows how to achieve a similar effect with conceptual cues.

The more puzzling the paradox, the more powerful the epiphany. We never forget an essay that pulls off a logical feat we didn’t think possible, reconciling the twain that we never imagined could meet.

Yet I’m forever reading first drafts that begin with rationales, not with riddles.

So what do the hedgehog, the fox, and the magister’s pox have in common?

I could tell you, but I won’t. And Stephen Jay Gould will take his time letting you connect those dots for yourself.

Most of my content in 2025 is free, but I appreciate the support of readers who make my writing life possible. Monthly installments of my memoir-in-progress are only available to full members. For access, please consider upgrading your subscription. I’m also proud to be a Give Back Stack. 5% of my earnings in Q4 will go to Centre County PAWS, a no-kill shelter focusing on adoption, education, and community assistance.

See my accountability page, with receipts for Q1, Q2, and Q3 here.

I find Ben Percy's THRILL ME is a superb book on craft, whether you are writing a thriler novel or not. Especially this chapter!

As someone who grew up in Lincoln, A Novel Idea remains one of my favorite bookstores of all time - glad you had the chance to meet Cinnamon (and hopefully Katherine as well)!