A few weeks ago while watching the Nebraska Cornhuskers, like a dog who can’t resist his own vomit, I was shocked to see Nobel Laureate Thomas Cech appear in an ad for the University of Colorado. Cech won his Nobel in 1989 and still teaches Chemistry in Boulder, so it wasn’t surprising that the university would market his accomplishments. It was the words he said that stopped me cold.

The ad is a riff on Deion Sanders’s nickname, “Primetime.” What’s special about the University of Colorado? Prime research, prime alumni, prime location, and – in Cech’s words – prime faculty.

If you don’t follow college football, you may be unaware that Colorado hired Sanders to revive a program that won just one game in 2022. Coach Prime, as his players call him, is an NFL Hall of Famer with just three years of coaching experience. He was seen as a risky hire, but CU Chancellor Philip DiStefano made it plain that the university was banking on Sanders’ celebrity to elevate the university brand.

That gamble paid off when Colorado upset Texas Christian University on September 2. Just a day later, the university released the 30-second spot that opens with Cech and ends with Sanders. Three weeks into the 2023 season, Sanders’ Buffaloes were undefeated and every remaining ticket had been sold. Even after recent losses to Oregon and USC, DiStefano’s roll of the dice looks brilliant, as every casino payout does. But make no mistake – Coach Prime is not promoting scholarship that represents the greatest benefit to humankind. It’s the other way around.

The Nobel Laureate is now the face on the cereal box of college athletics.1

For more hard-hitting polemics about higher ed, such as this one comparing the reality show Alone to graduate school or this one suggesting that humanities professors need a divorce from their institutions, please consider upgrading your membership.

The corporatization of higher education has made this reversal of priorities seem inevitable. Branding has eclipsed mission, we have been told, because marketing is indispensable to a university’s long-term survival.2 But this reasoning derives, in part, from the myth that college athletics are inherently profitable. In fact, all but 25 U.S. universities lose money on athletics every year. While the University of Colorado football team typically records a profit, its revenue was not sufficient in 2022 to offset a $13 million deficit from athletic spending. The university subsidized $8 million of that shortfall from its operational budget, which includes state funds and tuition revenue.

Colorado’s finances are more the rule than the exception. Even at profitable schools, less than $1 out of every $100 in athletic revenue goes to reinforcing academics. But when an athletic program dips into the red by underperforming or by amassing renovation debts, the subsidy often works in reverse, with administrators skimming from academic programs to cover investment in sports, hoping that success on the field will boost the university brand overall. Some athletic departments, such as the University Athletic Association at the University of Florida, maintain complete financial independence from their host institution. Other institutions, like Nebraska, rely on private donors to offset major losses, such as buyouts for fired coaches (Nebraska has paid more than $50 million in buyouts since 2005). But there is no universal standard for how the money flows in college athletics, and the chaos created by these high-stakes wagers destabilizes institutions that are already on the verge of collapse.

Branding damages higher education because it is driven by dominance. The social history of branding includes punishments for criminals and heretics, as well as the degradation of animals through domestication and of humans through slavery. An institutional brand necessarily creates winners and losers among its faculty, and this has typically led to a relentless promotion of STEM and a quiet suppression of the humanities and social sciences (except when a white-haired Thespian looks good on a brochure). Perhaps Cech’s colleagues have grown weary of hearing about his Nobel. But Cech now has real reason to wonder whether he is the institutional brand or whether Coach Prime has sizzled his own mark into the venerable professor’s flesh. This is the hidden cost of financial roulette through athletic branding: that the meaning of the enterprise erodes, that the individual’s sense of importance to the university is damaged beyond repair.

Athletic success can boost a university’s market share for a time. Such was true for Texas A&M in 2012, when Johnny Manziel won the Heisman Trophy. The university reportedly raised $740 million in private donations that year. But there was no way to predict Manziel’s meteoric rise. And every boom eventually goes bust. That Gold Rush mentality is just as harmful to university culture as it is to the young people caught up in the pressures of celebrity. It nearly cost Manziel his life. And those branding strategies backfire when young people do dumb things, such as urinate on a rival’s logo on camera, or when coaches push their team culture too far.

It is also difficult to square the unrestrained spending in college athletics with the austerity imposed on academic programs. West Virginia University recently eliminated 28 majors and cut 143 faculty positions while the athletic director, Wren Baker, claimed that the athletic department wasn’t spending enough compared to its peers. That disparity, alone, ought to expose the canards about athletics keeping academics afloat. WVU’s president, Gordon Gee, writes that “Most nonacademics do not care about research volume, or a university’s number of national prize-winning faculty.” Let that sink in: the highest levels of professional achievement simply do not matter to a college leader pandering to the public. If Cech taught at WVU, Gee might well see him as more of a branding liability than an asset.

A colleague recently shared this gem from the Syracuse Hancock International Airport. It’s got to hurt to teach at a university that spends thousands of dollars on such insipid slogans, which are meant to map directly onto athletic fandom. What does “Rise as One” or “Rise as Orange” even mean? It reminds me of the term “Kenough” from the Barbie movie, which Freddie deBoer rightfully describes as a “deepity, an empty placeholder for a message.” I mean, seriously. George Saunders teaches at Syracuse. Mary Karr teaches there. Tobias Wolff got his start there. And this is the best language the university can find. Did anyone think, if I’m reading the symbolism here correctly, that the rising sun must also set, that orange is more characteristic of evening than of dawn?

🔹

The federal government typically regulates economic forces that spin out of control. But universities are classified as nonprofit organizations and are governed by state law. No state legislator would suggest imposing limits on coaches’ salaries or stiffer taxes on television revenue from college sports, because doing so would be political suicide. The National Collegiate Athletic Association has no real regulatory authority, either. Universities could withdraw their membership in the NCAA just as many schools are switching athletic conferences in naked grabs for more television revenue. The Supreme Court’s ruling in NCAA vs. Alston opened the door to unlimited sponsorships for college athletes. Deion Sanders’ “Primetime” slogan is now the standard that every athlete strives to meet through Name, Image, and Likeness deals. Institutional branding is futile, because the particular identity or culture of an institution is secondary to the personal brand.

Justice Kavanaugh claimed, in his written opinion on Alston, “Nowhere else in America can businesses get away with agreeing not to pay their workers a fair market rate on the theory that their product is defined by not paying their workers a fair market rate.” But no one knows what the fair market rate is in college athletics anymore. And it might just as easily be said that nowhere else in America do businesses spend billions of dollars gaslighting their customers about what their product actually is. The NCAA tried to maintain that the true product offered by colleges and universities is education. But education is now a garnish to the entrée offered by the athletic department.

As one of my LinkedIn readers suggested recently, one of the few ways the current business model for higher ed makes sense is by comparison to cable television. Alyssa Pearson, a recovering academic who now works in project management, wrote that the product lifecycle for academe “has moved from the growth stage…[to] the maturation, maybe even decline stage.” All those consultants and administrators that I liken to the Communist occupiers of Czechoslovakia? Pearson argues that they “are all basically treating this in the same way as the cable television companies are treating their declining memberships. Trying to add new enticing services, chopping off things customers aren’t excited about, [and] becoming increasingly too heavy with crisis managers.”

Will Cech’s Chemistry department see a dime of the revenue generated by this year’s upstart Buffaloes? Or will the income flow back into more TV ads, strength coaches, and fancier locker rooms? And who will make up the deficit if the Deion Sanders experiment begins to look “Subprime”?

Sanders made headlines again recently for trademarking four popular catchphrases from his brief tenure at Colorado, including “Prime Effect” and “Coach Prime.” The next time the university runs a TV ad, it may need to pay its famous coach royalties for his slogans, in addition to the $29.5 million it has already committed to paying him over the next five years.

🔹

I hear you there in the back hollering that none of this is new. Football coaches have been the highest-paid public employees in their respective states for much of my life. The sheer scale of athletic marketing caught my attention as a graduate student at Nebraska in 1997, when I discovered that the university had a contract with Pepsi and the football team had a separate contract with Coke.

But now 80% of the highest-earning state employees are head coaches. And even those high salaries might not be sweet enough. Earlier this year, Mack Rhoades, Athletic Director at Baylor University, voiced concerns about how name, image and likeness (NIL) compensation and revolving doors in the transfer portal have made college football less attractive for college coaches. His speculation that elite coaches may simply walk away from the game is reasonable, given that the trend is already affecting basketball programs at the top levels. Some of the most decorated coaches in NCAA history, including Mike Krzyzewski, Roy Williams, Jay Wright, and Jim Boeheim, have explicitly stated that the transfer portal influenced their decisions to retire earlier than they might have under different circumstances. This is something new under the sun, is it not?

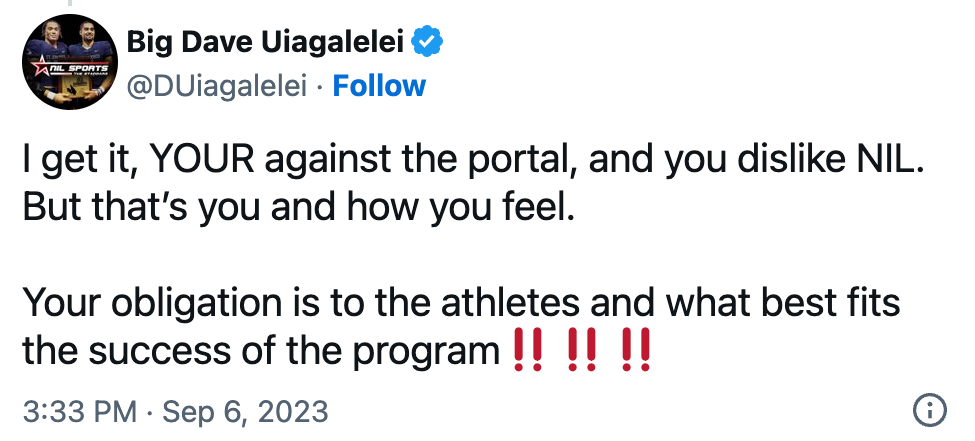

I actually have some sympathy for Dabo Swinney, head coach at Clemson and winner of two national titles, for dealing with public criticism from one of his former players, whose father can’t resist piling on.

When even top-rated coaches like Swinney begin to lose faith, surely the sports boom is ready to bust. Nearly every gripe that coaches or fans might level at players who privilege their own business interests over team loyalty can be leveled at academic institutions. Free market capitalism might be great at generating revenue, but left unchecked it creates ghettos, ghost towns, and thousands of acres of clearcut forests.

Sports are supposed to be fun, and fandom is meant to be a shared experience between family and friends. I played baseball from T-ball through college and have fond memories of high school basketball and football — pounding the hardwood with my hands to get low on defense, breaking into the open field as a running back, feeling a kind of religious ecstasy when I found the sweet spot with my bat. But even coaches agree that this isn’t what athletics is about anymore.

I write this with a sense of urgency, but I know all too well the impotence of my argument. A surge of courage, human sacrifice, and political will toppled the robber barons from their gilded perches in the early twentieth century. But there is no such majority interest now. The average person wants their flagship team to win. More tears are shed over losses to rivals than over furloughed faculty. The solution to the problem is regulation, just as it was for Standard Oil. But I won’t hold my breath that it will happen.

The futility of the case is captured by a scene from The Wire. Marlo, the latest kingpin in Baltimore, walks out of a corner store with a lollipop that he didn’t pay for right under the nose of the security guard. The officer follows him outside and says, “What the fuck? You just clip that shit and act like you don’t even know I’m there.”

“I don’t,” Marlo says.

“I’m here,” says the guard.

“You want it to be one way,” Marlo says. “But it’s the other way.”

The Nobel Prizes have their own baggage. Just 3% of Nobel laureates have been women, and not one Black scientist has ever been honored. Clearly there are systemic problems here that call the meritocracy of the award into question. For some, this television ad might represent a kind of intractable irony — Sanders is one of a handful of Black head coaches in college football, and Cech parroting the coach’s slogan might be an example of decolonizing the university. Yet it’s clear that nothing carries more currency as a marker of academic or artistic excellence than a Nobel, Pulitzer, or other major award (MacArthur, Guggenheim, fill in the blank). I’d need a separate essay to think through how I feel about the ad trading on that currency, which has its own damaging effects on institutional culture and morale.

As a reader of an earlier draft pointed out, this shift in priorities is not a nefarious plot. It began in the 90s when state legislators tied funding to enrollment growth. Enrollment then became a salient data point in the rankings race, along with senior leaders’ perceptions of quality at peer institutions. Malcolm Gladwell’s “Lord of the Rankings” fleshes out this back story.

This has bugged me for a long time and it starts in high schools. Athletics are always funded more and at the expense of other programs.

As for the Supreme court ruling allowing college athletes to make money- this is infuriating. Colleges give student athletes free tuition along with other perks. There should be a clause that if they make money from endorsements in college, they at least have to pay back their tuition.

Great piece. Most folks love sports, either playing or watching. That can’t be said for chemistry or composition. Universities should be promoting the latter, but they just can’t help themselves, now that they have turned into corporations.