There Is No Wildness In "The Wild Robot"

This past weekend I took my daughter to the movies. It’s tough to find one-on-one time with my kids as a single father of three, so now and then I hire a babysitter and take one child out for the evening. That’s how I found myself watching The Wild Robot on the big screen.

The Wild Robot has most of what you’d expect from a mainstream film: an internally conflicted hero, a wisecracking sidekick, and oversized doses of adrenaline and schmalz. But it also feels ambitious in a way that I don’t expect from a kid’s movie. So I’ve been puzzling over it ever since.

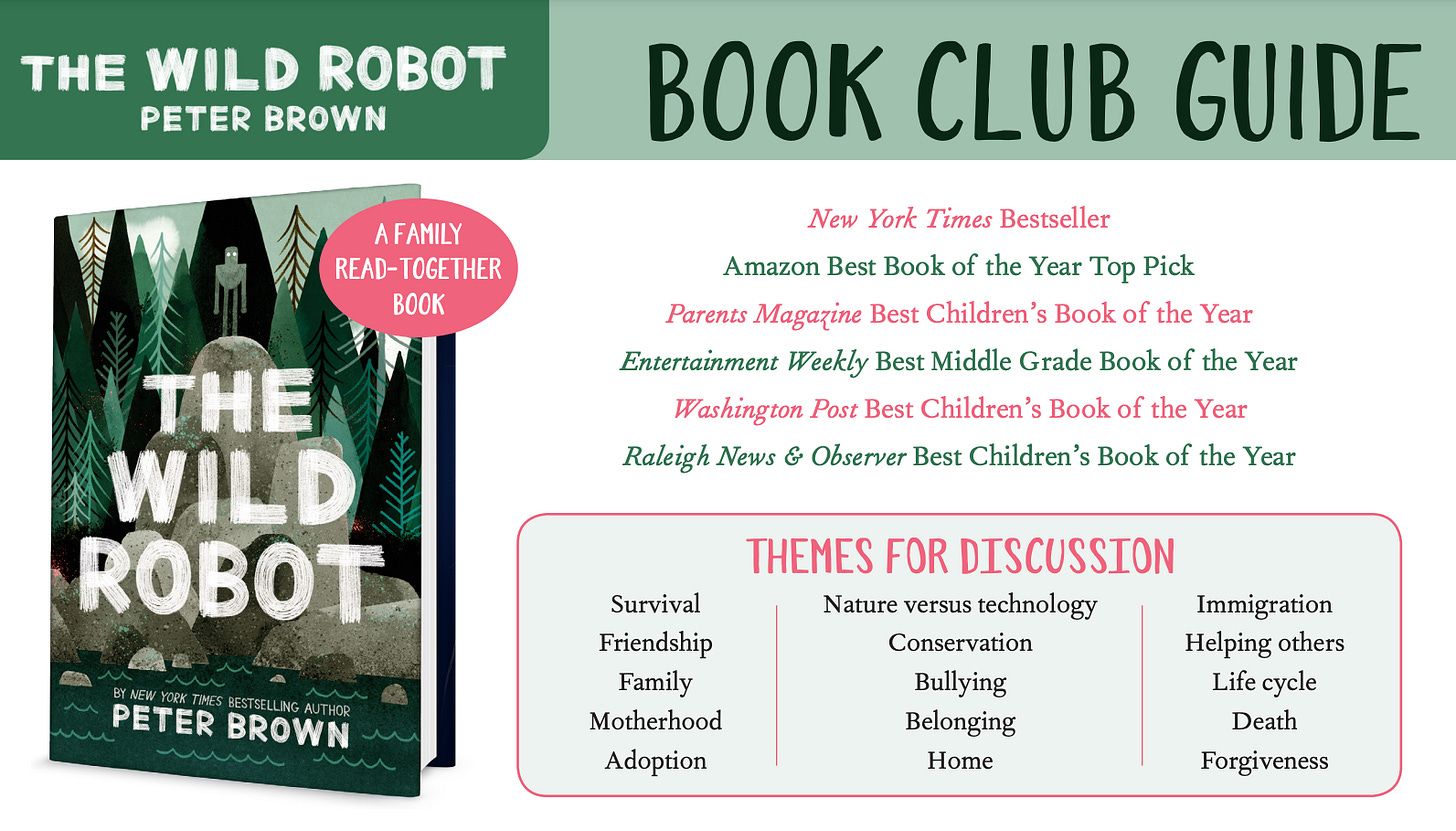

The film is based on Peter Brown’s eponymous book series. If you think I’m straining to make sense of a film that should just be fun, keep in mind that The Wild Robot has a book club guide. Based on the sprawling list of themes for discussion, there is at least some intentionality behind the characters and the narrative arcs, so it seems fair to probe those possibilities. But if you care about spoilers, you might want to bookmark this post, because there will be plenty of them.

The film and the book are both driven by a question: can a robot learn to survive in the wild? If you can suspend disbelief about an electronic device weathering shipwreck and exposure to the elements, this is the most interesting part of the film. During a typhoon, the ROZZUM unit 7134 (“Roz”) washes up on the shore of a heavily forested island, presumably somewhere near Alaska or Seattle. When a group of curious sea otters turns her on, Roz has to learn how to navigate the rugged landscape, survive hostile creatures, and alert manufacturing headquarters that she needs rescuing.

Learning capacity is AI’s most fascinating and terrifying capability, and there’s enough plausibility in Roz’s mimicry of wild animals to keep me in the viewing dream. In one scene she learns how to scale a cliff by imitating a crab, in another she learns to bound like a deer, and perhaps most preposterously she can imitate a skunk’s spray by creating some kind of internal short-circuit that produces an awful smell.

Once Roz realizes that she is failing to communicate with wild animals, she sinks into a catatonic learning mode in which she absorbs everything around her for days on end, ultimately translating that data into a universal language that allows her to communicate across species (presumably the animals can already understand each other). Not as elegant as C.S. Lewis’s talking beasts, but not implausible within the world of the film.

Roz has been programmed to be a home helper who completes every task, but none of the animals have any assignments for her until she stumbles into a grizzly’s den. During her flight from the enraged bear, she falls into a goose nest, crushing all of the eggs but one. Roz tries to study the egg, rescuing it a few times from a fox named Fink, before it hatches. The gosling imprints on Roz, which confuses her until a helpful mother opossum explains that Roz has a job now, and it is motherhood. She even has three clear objectives: to teach the gosling (later named Brightbill) how to eat, swim, and fly in time for the fall migration.

I enjoyed these craft elements as my daughter nuzzled against my arm. In fact, I could imagine teaching the film as a masterclass in plot. No sooner than Roz escapes one threat, she has a new problem to solve. The complexity of mothering a gosling has built-in rising action, natural peaks and valleys of conflict and reflection, and a looming climax of separation. The film is well-told throughout with callbacks, irony, and the paradox of bonding deeply with a child even as you know that someday you’ll need to let go, that your real work as a parent is rendering yourself obsolete.

It is hard to pinpoint when the problems creep in. Roz’s rescue transponder is damaged early in the film, so she has to search among the wreckage for another working unit. When she activates another robot, Roz learns enough of her past to know that she has overridden her programming and needs to return “home” to be set right. She also knows that her journey has changed her, that she won’t necessarily belong with her kind anymore. Nevertheless, she’s able to salvage a working transponder, which she triggers just long enough to be “seen” back at headquarters, where the rescue operation shifts into gear.

Aside from a few workers scurrying between screens at the corporate office and a fictional family in an advertisement for the ROZZUM robot series, there are no humans in this film. This is a problem, because Roz has no reason to exist without humans. She has been built to be the ultimate helper, doing everything a real person might find onerous, from laundry to landscaping. The film doesn’t say it, but you might surmise that Roz is meant to fill the domestic labor gap.1

Most children’s films have a double voice. Slapstick and moralizing (such as how to overcome bullying) are for the kids, and the higher flying themes are for the parents. It’s on this higher plane that The Wild Robot loses me. For instance, I’m not sure why a device created to do work typically done by housewives would be gendered female. Was this just a lapse on the part of some hidden engineer? An oversight by Peter Brown, the male author of the book series?

There is some not-so-subtle feminism in the idea of Roz struggling to override her programming and claim a more natural (?) wildness. But if that is an intentional subtheme, why would all of the robots in the film be so conventionally gendered? The attack robots back at headquarters and the Storm Trooper types who try to rescue Roz are all curiously buff, as if musculature means anything in robotics. Similarly, a “retrieval robot” named Vontra is a sinuous female with metallic tentacles who has been programmed to lure rogue units with her charm before strapping them to a chair and sucking their memories out in the name of research.

All of the wild animals in the film hew to predictable types, as well. The ferocious bear is male, as is the sly fox and the runt gosling. The mothers are the only grownups in the story; everyone else is an emotional child. The mother opossum complains about her children in all the ways we’ve come to expect, but despite her weariness she remains competent. Roz follows her marsupial friend’s lead and even goes so far as to single-handedly rescue the island’s inhabitants from a cold snap that might have killed them all, gathering them into a lodge that she copied from a beaver’s design. While the animals bicker like siblings, Rozz urges them to set their instincts aside at least long enough to make it to spring.2

At this point I was no longer dreaming the film because I was distracted by too many questions. We are supposed to root for Roz in her escape from headquarters, her liberation from her oppressive programming. But she also seems to urge wild animals to give up their own wildness, setting aside the troublesome tooth and claw for a kind of mutual aid that has only ever existed within species, and precious few of those. So in this sense, both the ROZZUM code (a robot’s equivalent of socialization, I guess) and wildness seem to be irreparably flawed. If you’re following your instincts, you’re doing it wrong. Goodness, wellness, a better way of being is only possible by overhauling your whole makeup. But just where this imaginary morality comes from remains a mystery.3

I will confess that I left the film sad, but not in the ways that Peter Brown intended. The human world that I see is still very red in tooth and claw. I do not believe that children need to be sheltered from this reality, even if some moderation in that education is required. My own children seem to agree, since they are huge fans of Adam Gidwitz, who retells the goriest versions of Grimm’s Fairy Tales.

As we walked out into the cold and stopped for a glimpse of the stars, I thought about how much I prefer the world of Beatrix Potter. Potter’s works have been cutsied up by illustrators and animators, painting a false impression of her stories. In Potter’s telling, Mr. McGregor would love nothing more than to turn Peter Rabbit into a pie. As a gardener who lost several lovely butternut squashes this year to a tooth-gnashing groundhog, I can sympathize. In Potter’s “Tale of Mr. Tod,” a badger named Tommy Brock kidnaps a whole family of bunnies, fully intending to roast them for dinner while squatting at the home of Mr. Tod, a fox. The bunnies get rescued in the end, but not before a terrible brawl between the badger and the fox, who are both pretty nasty fellows.

You don’t come away from Potter’s works with a romantic view of nature, which is as it should be.4

Another thing that Potter gives us that The Wild Robot does not is fathers. I’ll admit that it was hurtful to have planned an evening with my daughter, to have identified so strongly with the subplot between Roz and Brightbill, then to realize that I simply did not exist within the world of the film. If there are fathers in The Wild Robot, they are absent, like the deadbeat daddy opossum.5

On the drive home my daughter yawned happily in her booster seat. All she could talk about was how cute the baby opossums were, how funny Fink the fox was, how much she enjoyed the evening. My heart warmed back up knowing that she’d look forward to our next daddy daughter night.

But after I put her to bed and started my own bedtime routine, I thought about how far back the pathetic fallacy goes for robots. At least as far back as C-3PO, with his impeccable manners, and his adorable sidekick, R2-D2. Maybe even farther back than that, to L. Frank Baum’s industrial Tin Man, who gains the heart he was created without. We keep thinking that machines will mimic us so well that they’ll take our place. We keep forgetting what Ellen Ullman reminds us in her wonderful essay “Dining with Robots” where she has an epiphany at the supermarket about how robots are already turning us into themselves.

What scared me…were the perfect limes, the five varieties of apples that seemed to have disappeared from the shelves, the dinner I’d make and eat that night in thirty minutes, the increasing rarity of those feasts that turn the dining room into a wreck of sated desire. The lines at the checkout stands were long; neat packages rode along on the conveyor belts; the air was filled with the beep of scanners as the food, labeled and bar-coded, identified itself to the machines. Life is pressuring us to live by the robots’ pleasures, I thought. Our appetites have given way to theirs. Robots aren’t becoming us, I feared; we are becoming them.

I went to the store today, and there wasn’t even a human cashier in sight. I scanned my own items and followed the soulless female voice’s commands. After picking my kids up at school, I’ll allow them a little screen time, and the house will fall silent as their iPads flick on. For those twenty minutes, wildness will be the furthest thing from their minds.

Yet that is precisely the story about technology that we ought to be telling our children. We never find a heart for the Tin Man. He always lures us into surrendering our own.

Here the film politely sidesteps the questions about privilege that must accompany any technology as sophisticated as the ROZZUM 7134. Whoever the families are that can afford a robot this advanced, they must be living in bubbles of their own. If instead of learning how to mother a gosling, Roz had stumbled instead into a logger’s home, the story might have taken a more interesting turn.

I wonder if this bizarre scenario is what the publishers had in mind when they listed “conservation” as a theme in their discussion guide?

This sounds an awful lot like Dr. Becky, founder of “Good Inside” (your 24/7 Parenting Coach!), who famously claims that we ought to assume that everyone, including our kids, is doing the best they can and just needs a little help through whatever hard time they’re having at the moment. Similarly, there’s no wildness in The Wild Robot that can’t be tamed, no shadow side with any real heft to it.

And Peter Rabbit isn’t “good inside” — he’s tormented by competing impulses and just as often loses that struggle.

If there is to be progress in socializing young men to be better fathers who foster equity within the traditional family home, perhaps authors of children’s books might consider making fathers visible as competent caregivers with reliable moral compasses of their own.

On this review, the gendering of the robots, and footnote 1, I wonder if you have read Kazuo Ishiguro's Klara and the Sun? This novel is about a robot nanny and does a really good job of grappling with these questions, as well as the disposability of the robots, and love for individuals qua unique individuals in an atomized, consumerist world. Highly recommend if you haven't already read it.

Also, a pedantic note: "setting aside the troublesome tooth and claw for a kind of mutual aid that has only ever existed within species, and precious few of those" is itself a view of nature that comes out of the industrial revolution and capitalism. Arguably the most successful group of animals of all time is the hymenopterans, the group that includes ants, bees, and wasps--all extremely social. "Nature red in tooth and claw" was a popular line from the Tennyson poem for social Darwinists like Herbert Spencer (the coiner of "survival of the fittest") to appropriate to underscore how nature is, like, super selfish and that's why we shouldn't have any social welfare programs. It's interesting to note that even in the late 19th and early 20th century, many naturalists noted that mutual aid across species was extremely common--it's just that (in the west) they were ignored by the mainstream scientists (who happened to be wealthy and pretty big fans of capitalism themselves.)

One of these was Beatrix Potter, whose work illustrating lichens helped to prove that lichens are mutualistic associations across not just species, but kingdoms (a fungus and a plant). The Royal Society would not accept Potter's work, though, because of her gender and because of the mutualistic conclusions it supported.

"The Wild Robot has most of what you’d expect from a Disney film: an internally conflicted hero, a wisecracking sidekick, and oversized doses of adrenaline and schmalz."

However, it's NOT a Disney movie, but a Dreamworks one. And therefore it's meant to beat Disney at their own game (as they have before), while being more faithful to Brown's novel than Disney itself would have allowed.