A few weeks ago I was splashing around in a local creek with my son when I ran into another dad I know from daycare. He is an academic, so we’ve talked off and on about my career pivot, and he asked what I was up to now. When I mentioned that I’d launched a coaching practice, he looked puzzled. It didn’t help much when I clarified that I was a book coach.

“What do you do?” he asked. “Cheer people on?”

He wasn’t being snarky, and I got what he meant. It reminded me of a cartoon I saw once, where a lost traveler discovers a box in the desert that says, “Save for Emergencies.” When he opens it, he finds two tiny men who shout encouragement. “You can do it!” “Don’t give up!”

The typical scholar doesn’t think they need a book coach. The way to write a book is to retire to the library carrel or shut the office door and just grind away at the thing. Maybe you ask a mentor or trusted colleague for feedback now and then, but really the book is a solitary endeavor.

The same mentality persists among memoirists and fiction writers. Here is Anne Lamott’s advice.

James Patterson offers much the same advice in his MasterClass course when he recalls his grandfather singing as he drove his delivery truck every morning. “If you’re not singing when you sit down to write,” he says, “something’s wrong. You need to fix that.”

It’s unreasonable to expect someone like Patterson to reveal the secret to his success, but I was hoping for more from his course than the suggestion that I write pages and pages of chapter outlines before even attempting my first draft.

Most writers know that plunking their butt in the chair accomplishes little if they have no plan for how to string paragraphs together or how to follow the seam of a story the way a miner traces a streak of ore. What’s the use of an outline if you have no sense of the larger design? Lamott and Patterson surely don’t intend this, but their advice is so vague that it often predestines failure.

Flannery O’Connor is rumored to have said, when asked if universities discourage writers, that they don’t discourage enough of them. Too many writers take that to heart. I plopped my butt in the chair. I tried outlining. Nothing happened. I must not have the stuff.

I’ve only been coaching for about a year, but the bulk of my work has not been fixing my clients’ attitudes or work habits. They already have ideas they believe in, they already know how to be alone in a room, and they have no trouble grinding away for two hours or more on a chapter. Their biggest problem is the planning stage, where a writer erects the scaffolding that allows a book to take shape. That, more than anything, is what I’ve been doing as a book coach.

Let’s say you have an idea for a novel or for a memoir. Maybe you know that you want to write something about motherhood or coming of age. You have some iconic scenes in mind, maybe you’ve published a few stand-alone narratives that you think could fit together in some way. But even if you’re assembling a linked story collection or a memoir-in-essays, you’ll need some unifying narrative arcs to hold the whole thing together. You’ll need a sense of that wholeness to know what you’re writing toward when your butt hits the chair.

So today I’ll share a few things that have worked for me and my clients in translating a book idea into a plan for completing the first draft. Think of these like three classic chords that you can use to write an infinite number of songs.

1. Start with a problem and write toward resolution of it.

Stephen King famously recommends situation over plot. Throw your character into a predicament and watch how they respond rather than predetermining all the elements of Freytag’s Pyramid. King’s advice is the opposite of Patterson’s, and I believe it allows more room for discovery. Instead of mapping everything out in advance, embrace the trouble the character is in and their struggle to overcome it. Follow that struggle wherever it leads.

Memoirs are driven by questions or a quest for meaning in the past. My memoir follows two parallel problems: my dislocation from fundamentalist Christianity and my geographic exile from the Mountain West. How do I come down from a religious mountaintop and reintegrate into the world? And how do I let Montana go, so I can embrace Iowa – a place with no mountains – on its own merits?

Similarly, Terry Tempest Williams links her mother’s struggle with breast cancer to the larger problem of vanishing habitat for migratory birds in Refuge. Braiding those two problems gives the book a shape that I imagine carried Williams from the idea through the initial draft.

Williams also shows how to link the personal questions to a larger concern, like cancer or extinction. If the questions driving your memoir are bigger than your own life story, then the stakes are higher. Elevated stakes pull you more forcefully toward a finished work in the same way that urgency will keep your readers engaged.

2. Identify the major turning point.

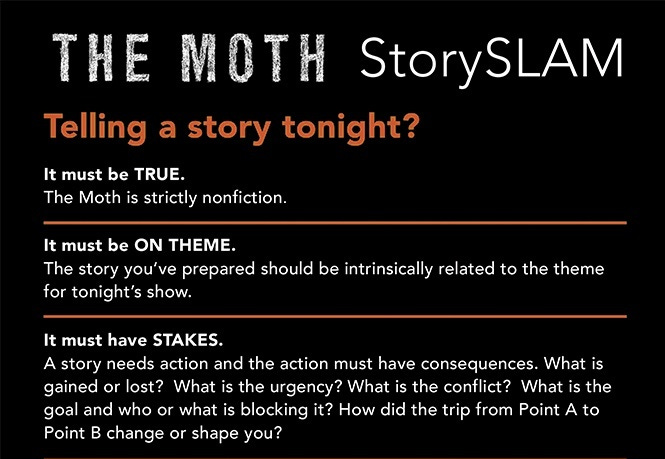

Nearly every story you’ll find at The Moth hinges on a single transformative moment. Moth producers want you to show how you came out of that experience changed. Old news, you might say – the classic plot climax. And it’s true that you can reverse engineer a story if you know exactly what happens at its apex. In Story Genius, Lisa Cron recommends writing the ending first and then using a series of complicated scene templates to flesh out the story leading up to that predetermined finish.

But I find it more useful to leave the big turning point unresolved early in your process. You know that your story is going to build toward this moment that will change everything. Perhaps it’s an all-hands-on-deck scene, as John Gardiner would say. But you don’t quite know what will happen then. You just know that the problem you set out to solve will have to turn one way or another at that juncture, the way a criminal trial leads to conviction or acquittal. As the Moth folks say, the action must have consequences.

But you can allow yourself some suspense as you write toward that revelation.

I knew that my memoir would eventually have to turn the corner from critiquing my religious upbringing to embracing a new value system. Exile should give way to belonging. I also knew that I’d have to stop seeing Iowa for its absence — the place with no mountaintops — and begin seeing it as a place where the infinite is more close-up than far off, where the universe manifests in a square foot of soil rather than in a long sightline from a granite peak.

When I set out to gather my essays into a book, I didn’t know how I’d resolve those two narrative arcs. I just knew that there would have to be a verdict on those questions. That clarity and urgency pulled me forward.

3. Map out some “tent pole” scenes.

There is a perennial debate about whether mapping or pantsing is the superior writing method. Should you plan every chapter the way Patterson does or scoff at the plan and just write blindly every day? I recommend a middle path that fills the gap between the inciting problem or questions and the big turning point when those conflicts are resolved. And that is to identify at least a few smaller turning points between the opening and the climax and rely on those for some general orienteering as you tackle the segments in between.

Pick your metaphor: either these scenes are like poles that keep your narrative tent from collapsing as you assemble it, or they are like cairns along a rocky scramble that you see from the base and aim yourself toward without knowing where you’ll find each foothold along the way.

This is the strategy that I used for my novel. That project is still searching for a home, but I have faith in it. I wrote the first draft in two months because I’d been carrying the inciting problem with me for a while. I also had a sense of the big turning point, and I took a little time to sketch out those middle scenes that would allow me to find my way from the opening to the reckoning.

This abstract captures the gist:

When he learns that his uncle Jesse has gone missing in northern Idaho, Ben Burns is twenty-five years old, working as a bicycle mechanic in Iowa and drifting through a dead-end relationship. After hunters find Jesse’s remains in the wilderness, Ben travels home for the funeral, wrestling with the ghosts that drove him away from Idaho originally and that might have drawn Jesse into a religious cult. Grief forces Ben to confront his mother’s mortality and his responsibilities to his aunt and his cousins, whose bereavement thrusts Ben into the supportive role that Jesse once offered to him. Facts emerge suggesting that Jesse’s death might have been a suicide, and when violence erupts during Jesse’s memorial service, Ben’s family must abandon decades of denial. As he struggles to understand Jesse and reconnect with his family, Ben finds freedom in embracing rather than erasing his past.

When I began writing this book, I didn’t know that the funeral would be violent. But I knew that Ben’s search for answers and the backstory to Jesse’s disappearance would need to detonate in some way at that memorial service where all the major players would gather to pay their respects. Chickens would need to come home to roost.

To get there, I knew that Ben would have to leave his failing relationship, that the funeral would require him to retrace the route from Idaho to Iowa that he’d originally chosen for escape, and that his homecoming would bring the past flooding back. There would need to be a rupture of denial and avoidance in that moment when he accepts his uncle’s death.

And so when I sat down to write each day, it was like waking up in a portaledge midway up a mountain, knowing that I was heading toward the summit that I could see, dimly, from my perch, but not knowing how I’d navigate each twist and turn in between.

I firmly believe that every writer needs some version of this plan before settling in at their desk. If you don’t mind spinning your tires as long as it takes to find traction, then more power to you. But you don’t have to struggle alone. A book coach can shave months off your process by helping you sketch your story’s route and identify the landmarks that will help you stay on course. Even with a guide, there are still a thousand original discoveries to make along the way.

If you have an idea that you’d like to make a reality, or if you have a manuscript that you’d like to take to the next level, I’d love nothing more than to tackle that challenge together. Check out my coaching website for more information on my rates and packages or my About page for a sense of what I’ve published.

This was so helpful!

I found this really useful, Josh. I'm thinking of putting my memoir essays together into a book and am trying to work out a narrative arc to bring them together. Your suggestions here have prompted me to think a little differently. Thank you.