Why It Took 20 Years To Publish This Book

The road over Lolo Pass from Missoula was slick with rain, but the melancholy felt right. I knew this was the last summer I’d spend in the Selway-Bitterroot Wilderness where I’d been a ranger for two unforgettable seasons. I always listened to Emmylou Harris’s Wrecking Ball and Daniel Lanois’s Acadie on the drive up from Lolo and down along the Lochsa River into Idaho. The bass and steel guitar caught the exact pitch of the forest.

The year was 2005. I’d just finished my PhD in Nebraska and accepted a full-time faculty job in Iowa. It was everything I’d worked for, but it meant the end of my summer work out West. The demands of teaching at a small college wouldn’t allow it. My Forest Service supervisor and academic dean were equally unhappy with me, one for cutting my tour short in early August, the other for arriving two weeks after my contract began.

I didn’t know then just how far my future would carry me from the place that had become my spiritual home. But I knew I had three golden months left to savor it. As I turned onto the gravel road where the Lochsa and the Selway merge to form the Clearwater, I could feel a plan taking shape. I was going to write a hundred poems that summer and turn them into a book.

It took nearly twenty years to make good on that promise. This is the story of how Someday Johnson Creek came to be.

There are many kinds of wilderness rangers. I was foreman of a trail crew, which required backpacking into a remote station and working for ten days at a stretch clearing fallen trees and brush from the trail, sometimes repairing tread or small bridges. Gas engines are prohibited in wilderness areas, so we did all of our work with crosscut saws, axes, and other hand tools. We ordered our food by handheld radio, and a packer delivered it by mule every ten days.

Backcountry trail maintenance is some of the most grueling work I’ve ever done. We often covered 40-60 miles over ten days, carrying our supplies, shelter, and tools on our backs. It was my job to plan the routes, triage work priorities, and keep us all safe. This little pamphlet was my guide.

It is hard to write poems after swinging an axe all day, so I filled several notebooks with fragments and devoted my weekends to translating those notes into verse. Even if I didn’t have the mental energy to draft anything at the end of the day, I was gathering images and ideas while hiking, sawing a fallen cedar, or reshaping tread with a pick mattock. Often inspiration came in the form of metaphors which I imagined sharing with friends and family back home. When I made it to the Moose Creek cabin for four days of R&R, I spent that time reading and drafting my poems longhand on legal pads.

What did I read? So many lovely books. Gary Snyder’s Danger on Peaks and Mountains and Rivers Without End, Louise Erdrich’s Original Fire, Billy Collins’s Sailing Around the Room, Rita Dove’s Thomas and Beulah, Charles Simic’s Jackstraws, Joy Harjo’s She Had Some Horses, Yusef Komunyaaka’s Talking Dirty to the Gods, Ted Kooser’s Sure Signs and Weather Central and Delights & Shadows, Audre Lorde’s Our Dead Behind Us, Twyla Hansen’s Potato Soup, Sherman Alexie’s The Business of Fancydancing, Keith Ratzlaff’s Man Under a Pear Tree and Across the Known World, Sharon Olds’s The Dead and the Living and The Gold Cell and The Wellspring, Philip Levine’s The Simple Truth and What Work Is, Mary Oliver’s House of Light and American Primitive and White Pine, James Welch’s Riding the Earthboy 40, Wendell Berry’s Sabbaths, Dickinson, Whitman, Emerson, and more.

The journey from thought to word to the printed page is a perilous one. But I imagined myself in conversation with all the writers I read — and with readers who might have enjoyed those same books. If I sometimes grow impatient with writing online it’s because I miss that imagined communion. It’s the closest thing I’ve found to prayer, the feeling that I am bound to a reader I cannot see, the abiding faith that I can do for others what the writers I’ve read have done for me. I still feel that with you, dear reader, every week. But it is not the same as keeping the faith for months, even years, and then emerging from that silence with my very best work.

My favorite poems are those that assemble the raw materials for epiphany. And so my vision, so far as I can explain it, is to transport a reader to the place where I stood and provide the essentials for them to experience the same revelation. A poem finishes a little differently in every reader, and it’s true that you can’t control art once you’ve created it. But I wrote my poems out of literal isolation, not for myself, but to share what I saw with my eyes, felt with my body, and carried in the quiet of my heart.

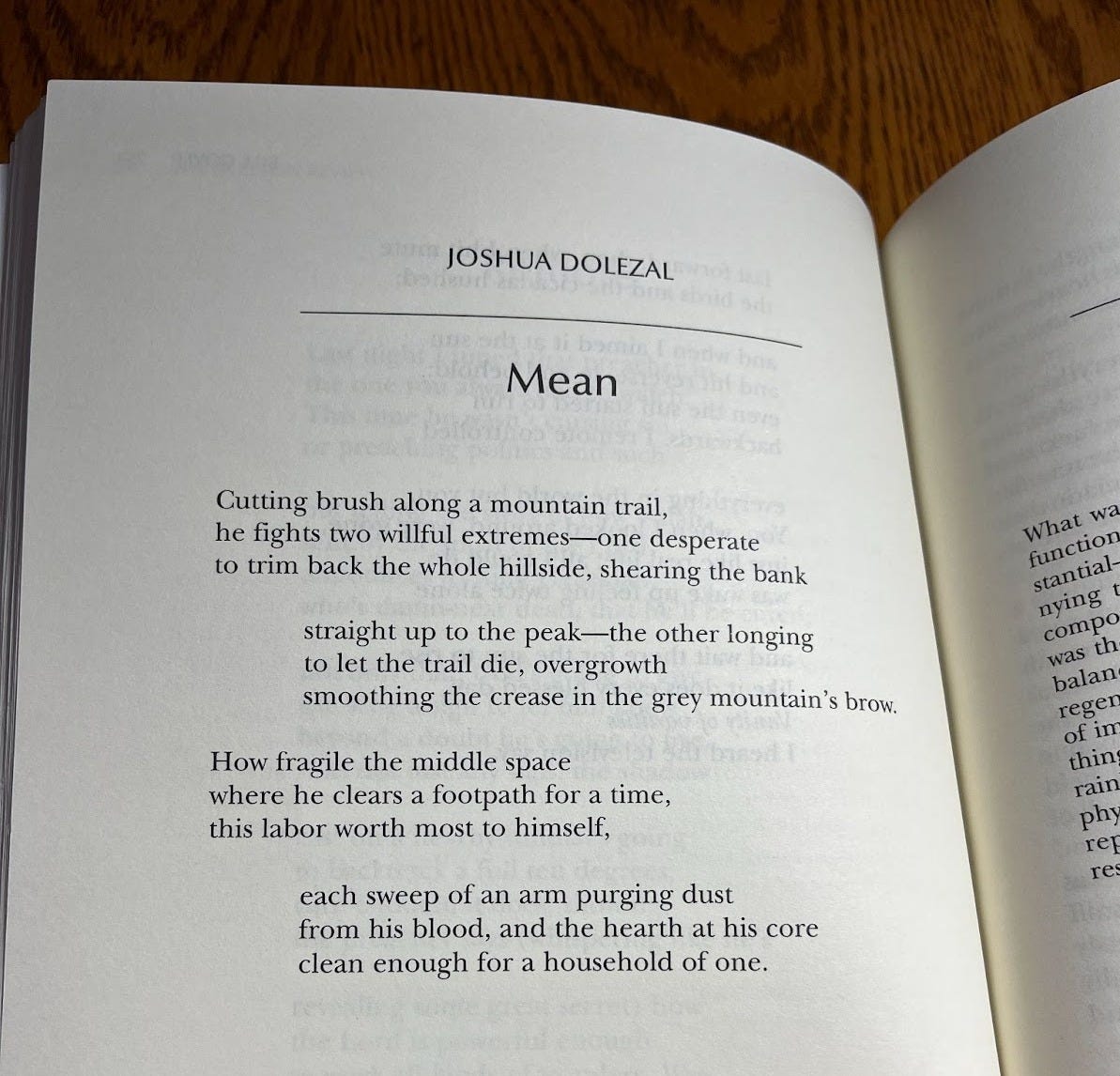

I drafted 120 poems that summer, but some of them fell flat, the way a dream fades in the morning light. Just 43 have survived. You can read some of them in my archive, including “Duende,” “The Helicopter Pilot,” “The Skier,” and “Little Damascus.”

—

The traditional way to publish a book of poetry is by placing several pieces in journals and then winning a contest. It’s a strange convention when you think about it, but nearly all of the accomplished poets I know got their first book deals by paying hundreds in entry fees before carrying away one of those coveted prizes. I also know many fine poets who never broke through.

One of my friends grew so frustrated at being selected as a finalist year after year that he buttonholed one editor at a conference and let him have it. Sometimes that’s what it takes. He won that magazine’s contest the next year, and clearing the first flaming hoop meant carte blanche with the same press for every new collection he published thereafter.

Several excellent journals have hosted poems from this book. I’ve even shared pages with Wendell Berry in The Hudson Review.

But after many years of plying contests, I came to understand that it was a fool’s errand. The poems could stand on their own, but it was clear from past winners and from the slates of judges that nature writing was no longer hip. Maybe the feeling was that it had already been done by Mary Oliver and Gary Snyder, maybe it was the old sneer from New York to Norman Maclean (“These stories have trees in them”).

Sometimes you need to keep grinding. Sometimes you need to read the room.

The choice in this case was to abandon a work of art that I believed in or produce it myself. It has been shelved for at least a decade, but after interviewing

about The Requisitions and following ’s pioneering work with A Memoir in 65 Postcards & The Recovery Diaries and In Judgment of Others, I knew that I wanted to share Someday Johnson Creek with you.Samuél helped me figure out ISBNs and copyright, and Eleanor pointed me to Reedsy, where I found my designer, Laura Boyle. I sent Laura a few of my own photos, she mocked up some covers, and we finally settled on a burnt alpine fir at the top of Lost Horse Mountain, looking toward El Capitan on the Montana side. Laura also designed the interior and set up the Kindle version. After several friends contributed blurbs, including Samuél and Eleanor, we were done.

—

Someday Johnson Creek is dedicated to the memory of Connie Saylor Johnson, my wilderness mentor and friend. Connie was a high school Spanish teacher in Iowa for many years, and she discovered the Idaho wilderness when divorce left her a single mother. After raising her daughters, she moved to Idaho and devoted the rest of her life to wilderness conservation.

Connie’s second husband, Lloyd Johnson, was a retired cop from Los Angeles. Together they raised horses and mules and spent their summers at Moose Creek. Connie’s favorite mules were named Lillian and Toad. Connie and Lloyd believed that instead of breaking mules, you should win them with warmth, with a loving touch. They were like that with me, too, generous with hugs, a clap on the back, a firm hand on my shoulder. Lloyd cooked huge stacks of pancakes for me and my crew at the Moose Creek Station. I can’t look at a Bisquick box without thinking of him. He nicknamed me Sawzall and emailed me salty jokes throughout the winter. Connie read my poetry, showed me all the secret water sources on the topographical maps, and packed our gear to the first campsite every hitch. I loved them both like my own grandparents.

Lloyd took a bad fall several years ago. His mule spooked at a bear and threw Lloyd down a steep slope, where he shattered his leg and broke several ribs. After a helicopter medevac, he survived for some time under Connie’s care, but I know they both wished he’d drawn his last breath on that mountainside. Connie wrote to me that town life was turning her into an “old bat.”

After Lloyd’s funeral, Connie went to work as a camp cook for an outfitter. She was so happy to get back out into the wild country she loved that she didn’t mind staying in camp alone. But one October day while the outfitter was out with his hunting clients, Connie disappeared. Despite a prolonged search, no trace of her was ever found, except that which all of us who knew her carry within us.

Connie loved the title poem in this collection. It is named for an actual place that I visited just once near the end of that last summer. Someday Johnson Creek is a feeder stream, bubbling out of an alpine spring to join other tributaries of East Moose Creek. I discovered it while my crew was working along a ridgetop where everything had burned to a crisp the year before. It is unnerving to hike through a moonscape like that where the ground is still black with char. But I’ve never seen anything like that creek. It was a ribbon of green running straight through the ash. The stream formed several man-sized pools before it dropped off the slope. It was a hot day, and I was glad to drop my pack, peel off my dusty clothes, and soak in one of those pools while I waited for my crew. Part of me is still waiting there.

So that is the story of this book. I’ll end with the blurbs, but I also have a favor to ask. I hope you’ll buy my book, of course, but I also need your help in spreading the word. It would mean so much if you’d restack this post or write an Amazon review. If you can’t afford a copy, but would still like to write a review, please message me and I’ll share the PDF. Thank you in advance.

Praise for Someday Johnson Creek

To spend time with these words is to be outside in rushing water, alive with hard stone and soft bark, to be amongst the wild with all its roar and pelt. Doležal is enraptured by his surroundings, and their essence pours throughs his fingers onto the page where we drink them in, are suddenly tumbled, washed, warmed and thrust out again and again into the landscape he loves. A collection dazzling in its claw, and raw with sudden personal sorrows. A delight.

Eleanor Anstruther, author of A Perfect Explanation

Each poem in this collection can be held in the hands of the reader and turned over, with shape, texture, heft, with physicality that defies what naysayers believe of poetry—that it is a no-thing. Here is visceral crunch; Doležal shapes living heart words inside iron rib works.

Alison Acheson, author of Dance Me to the End

In Someday Johnson Creek, Joshua Doležal transports us to the Idaho wilderness with all its haunting and redeeming realities. The book opens with his uncle’s brush with death after being shot while hunting and ends on grace notes with gratitude for being alive. In-between there are poems of familial cruelty and the raw days of being a wilderness ranger. Doležal exhibits considerable poetic skill on tough subjects without sentimentality or self-pity in this memorable collection.

Twyla M. Hansen, Nebraska State Poet and author of Feeding the Fire

If Ernest Hemingway had remained Nick Adams, had he allowed himself to be Nick Adams – pounding and hewing a love and pain-born self out of wood and wilderness – he might have been Joshua Doležal. Hemingway, of course, was never of Montana, where Doležal emerged both man, attuned to wild nature’s way, and writer. But Norman Maclean was, and he, too, fought wildfires and cut his own kind of narrative poetry out of the wilderness, worked and sought his soul there. Now, in a lean, taut poetry that at just the necessary moment exerts its lyrical lift, Doležal reaches not to conquer nature but toward a hard-earned union, seeking, as in ‘Geometric,’ ‘the square root of the sum / of this body, this earth.’

A. Jay Adler, author of Waiting for Word

Like a hiker venturing down an overgrown trailhead, in Someday Johnson Creek, Joshua Doležal offers a disquieting ode to the wilderness of the Americas. From poems about hauling lumber down gravel roads to the terrifying power of hunting rifles and pickup trucks, Doležal peers through the corrugated iron of rusted relationships, the price of hard labor that comes with an all-American work ethic, and the consistent reprieve to be found in the great outdoors.

Samuél Lopez-Barrantes, author of The Requisitions

I just ordered my copy! I'm looking forward to reading and sitting with your words in my hands soon

Congrats friend. Love to see this. The story of Connie and Lloyd is so beautiful and tragic but it makes so much sense, too, that they both succumbed doing what they loved