Friends,

Last week I wrote about the need to re-engineer a former self to show growth in an essay. Reconstructing growth requires choices about where to place the emphasis at crucial junctures — which notes to amplify and when. The larger goal is to make an essay go somewhere by its close. I don’t believe that is possible without risk.

This week I’m sharing a formerly unpublished piece that tries to do what Danielle Ofri models in “Merced.” I’ll resist the urge to preface it too much except to say that if the piece makes you uncomfortable, that is the point. It’s not the only point — I hope to turn a corner near the end. But my theme is mental illness and stigma. Please exercise discretion and stop if you need to. I look forward to the discussion.

Take care,

Josh

Darkness and Light

Lonnie, as I’ll call him, liked to trim his toenails on the edge of his bed where the clippings would disappear into the carpet. This should have bothered me more than it did, since we were sharing a room, but I had my side, Lonnie had his, and the toenail boneyard fell between his bed and the wall, a region I vowed would remain, for my part, uncharted territory.

So I put it out of my mind.

Lonnie was sandy-haired, medium height, a regular guy from Nebraska. He would have looked right at home in a military uniform from any American era. The room I shared with him was one of three bedrooms in a little duplex near the outskirts of Lincoln, Nebraska, maybe a mile from the state penitentiary.

The owners were the Bradleys1, a middle-aged couple who planned to spend the following year building a church in Mexico. Caden Bradley, their adult son, would stay on to keep an eye on the place. The only room left was the master, which held two beds. Lonnie had claimed one, and the Bradleys offered a cut rate for the other. I was about to begin graduate school in literature, and even though my tuition was covered by a fellowship, the poverty-level stipend that came with it made a solo flat seem extravagant. I told myself that it would be like dorm life, only with a private shower, and signed the lease.

The Bradleys flew to Oaxaca and the guys introduced me to their church, a monstrosity built among the subdivisions and commercial sprawl near Pine Lake, and we settled in to life together. Caden was short and scrawny with a wild head of hair. He took night classes and lived on his computer between trips to the grocery store in a rusted out Oldsmobile. Trevor, a pudgy undergraduate who had the downstairs room, was a gamer like Caden.

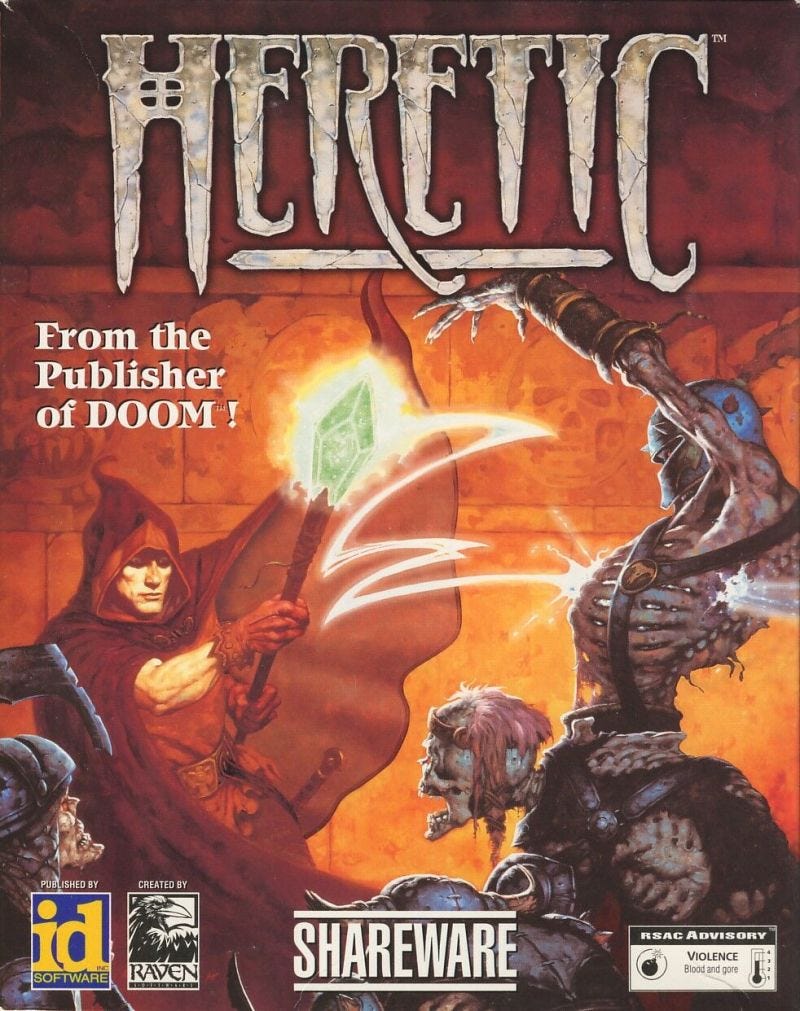

Sometimes the three of us linked our computers and chased each other through the medieval hellscape of Heretic, a shooter game that I loved for its crossbows and for the tall monsters who threw spinning battleaxes and let out a cry, something between a scream and a sigh, when they died and their ghostly souls drifted up and out of the picture. We killed each other hundreds of times on the screens in our separate rooms, reveling in the muffled shouts through the wall or beneath the floorboards when our weapons struck home.

I remember Caden and Trevor best for their nervous laughter when we startled one another in the hallway to the bathroom, still addled from the game, and our hands flew up, and each of us fired a dozen imaginary arrows into the other’s chest. It was difficult to read Dickens and Trollope after that — it took some time for the ghouls of Heretic to stop playing over the page — but even the worst of Victorian England felt like a balm after another virtual bloodbath.

Lonnie did not care for video games, especially the violent kind. He told me that he had crazy dreams as a kid and even chased his brother around the house with a knife one time while caught in a night terror. I knew he took some kind of medication at night, because he never stirred until his alarm pierced the dawn. He worked at an auto body shop during the day and spent most evenings with his fiancé, Maria. I rarely saw him except at breakfast and after dinner, when I’d have my books spread out in the living room and he’d nod to me on his way to bed. Lonnie’s alarm never bothered me, and he changed the oil in my car for free. If now and then over breakfast he came out with something strange, like, “You hate me, don’t you?,” I shrugged it off.

One thing about Lonnie that I couldn’t figure out was that Maria was out of his league. She was a nursing major, a curvy brunette who hid her figure in sweaters and skirts and had a smooth complexion that never needed makeup. It wasn’t that they looked wrong together, it was that Maria acted more like a nurse than a lover. She came home with Lonnie most nights, and the first time it made me blush when they walked right by me on the couch and disappeared into our bedroom. I gave up trying to read and listened hard through the wall, even though it wasn’t any of my business what was happening in there.

I was surprised to see Maria emerge after maybe ten minutes, scarcely enough time for a hug and a peck. She smiled and said good night and was gone. Some minutes passed before I could focus on my reading again, and when I felt my way through the dark and slipped into bed, I was certain that a trace of her coconut shampoo lingered in the air. I amused myself as I drifted off with the thought that a smell, which finds its way deep into the body, is not far from an actual touch.

After a few weeks of that, I asked Maria one night on her way out why she came home with Lonnie at all if she never stayed very long. It seems brazen of me now, but it had become part of the household routine. Lonnie and Maria coming in, Maria leaving alone. Caden and Trevor were always holed up in their rooms, so I was the only one who saw them come and the one who waved to Maria when she left. It was usually nine o’clock, at the latest, and I wondered why Lonnie couldn’t at least see her to the door.

What I really wanted to ask was why they seemed so chaste when all the other young couples I knew who claimed to be saving themselves did everything else they could justify short of coitus. It had been a subject of much debate at my Christian college, whether going down on a girl crossed the line, whether there were material differences between a hand job and a blow job or if all skin to skin contact below the navel was equally verboten.

But thinking a thing is close kin to doing it. It’s the heart the deeds flow out of that matters. By that measure the guys on the baseball team who hooked up once or twice a week and talked NASCAR the rest of the time were purer of heart than those who had never touched a woman but spent most of their waking hours imagining it. By the same measure, I wasn’t really asking Maria why she left so soon every night. I wanted to gauge whether she was disappointed by that and, if we want to get right down to it, whether her thoughts were anywhere near my own.

“Oh, I just tuck him in,” she said. “It’s no trouble.”

That answered one question, but it raised others that haunted me for weeks. Somewhere at the edges of my thoughts was the knowledge that I spent too much energy gaming these scenarios out, that there was a difference between studying the human condition empathically, as my professors claimed we were doing in literature classes, and simply prying into people’s lives.

I bristled at a classmate when she claimed she got most of her story ideas from airports, just by watching people walk by. “I see someone alone,” she said, “or a couple with a new baby, and a few seconds later I’m living in their world.” What a load of crap, I thought. Maybe it would pay to actually get to know someone before presuming what their world was really like? But that was more or less what I was doing with Lonnie and Maria. Even though Lonnie slept only a few steps from my bed, he was as inscrutable in most respects as any stranger. He was good at working on cars, helpful around the place. He liked Forrest Gump. He took medication that made him sleep heavily, and he was engaged to a woman who happily tucked him in at night. And he clipped his toenails into the carpet. This was really all I knew.

Like most young people, I thought I was good at turning the microscope back on myself. I had stumbled into Hotmail during college, and it was a revelation, that I could have instant exchanges with family and friends about theology, philosophy, everything that until then had been available to me mostly in books, where I felt at ease, and in conversation, where I did not. I wrote pages about Jonathan Edwards’s sermon, “A Divine and Supernatural Light,” Plato’s Republic, Henry Nouwen’s The Way of a Pilgrim. Time could fall away in front of the screen and the blinking cursor until I surfaced, as dazed as I was after hours playing Heretic, and tried to inhabit my body again. All those epistles now seem like little more than imaginary play, but I wrote them in earnest, as if I were Plato’s prisoner, unshackled from the wall where I had seen only shadows, making my way gradually from the firelit cave into daylight, always a little closer to the truth.

Darkness into light. I really believed it. These are the years, like adolescence, that we render comically or not at all when we consider how our adult selves were forged. It would be easier to forget the young man who spent hours playing Heretic, philosophizing, and speculating about Lonnie’s love life to compensate for his own loneliness. Rendering that younger self a harmless caricature would be another, perhaps equally dangerous, kind of blindness. Better to know that young person well, to speak of his errors plainly, to reveal what he could not see.

During that time I was still learning something that C.S. Lewis discovered late in life while grieving his wife’s death: that I could be sure of myself and be totally wrong. “Imagine a man in total darkness,” Lewis writes. “He thinks he is in a cellar or dungeon. Then there comes a sound. He thinks it might be a sound from far off—waves or wind-blown trees or cattle half a mile away. And if so, it proves he’s not in a cellar, but free, in the open air.” I craved those moments, when a phrase or the sustained experience of a book tilted my axis and I saw everything differently thereafter. But I had not yet learned how to apply such insight to real people. Like my classmate who thought she could know someone well enough at a glance to tell their story, I was pretty sure that marrying Lonnie would mean that Maria was consigning herself to a life sentence. After she opened up to me one night, I knew it for a fact.