Danielle Ofri taught me how to turn myself into a jerk in nonfiction. It’s possible that I don’t do it enough. Because if I can’t see myself as a jerk, even temporarily, I might not be showing enough growth in my essays.

Around the time I started writing my memoir, Ofri got her first big break. I’d been following her work in smaller journals, then The Missouri Review called her up to the big leagues. Stephen Jay Gould chose her TMR piece for the 2002 Best American Essays, an agent found her that way, and she got a book deal with Beacon Press. She’s now published seven books with Beacon. That’s how traditional publishing once worked.

The essay was “Merced.” You can read it for free on Ofri’s website. Or as part of her debut memoir, Singular Intimacies.

Today I’ll use “Merced” to think a little about where to place the emphasis, and when to shift that emphasis, as you develop yourself as a character in memoir.1

Let’s start with the foundational premise that an essay ought to show growth in the narrator. Just as readers expect a short story to resolve some of the problems it poses at the outset, so they hope that an essay will go somewhere. Even if all the loose ends don’t get tied up, readers don’t want to end up right back where they started with a narrator who hasn’t budged an inch.

But it’s very hard to reproduce your own growth in hindsight. You’ve already been changed when you sit down to write. How do you show transformation in yourself-as-narrator if you begin an essay knowing how it will end? Doesn’t this violate one of the basic principles of good writing, that if you don’t surprise yourself you won’t surprise your reader, either?

The answer might seem like a dodge, but it’s true: you must reinvent your past self. Sometimes that means you have to turn yourself into a jerk, at least for a little while.

“Merced” opens at a medical conference where Ofri is the star of the show. Three weeks earlier she had diagnosed one of her patients in New York City with Lyme Disease after two ERs had mistakenly treated her for bacterial meningitis and herpes encephalitis. It was a shocking diagnosis in the inner city. The case was being presented at neurology grand rounds, and Ofri mused that she might publish it in the New England Journal of Medicine. Ofri’s patient, a woman named Mercedes, even attended the conference, glowing with good health.

At the time, Ofri was nearing the end of her residency. She was a woman thriving in a male-dominated profession after overcoming a serious case of imposter syndrome during her first year. I really can’t picture her, even at her most sleep-deprived, as a jerk. But she had to make herself one for this essay to land.

“I was a little cocky that day,” she admits. She recalls scolding the ER hacks and making “a big show” of canceling the medication they’d ordered. Ofri walks us through her examination of Mercedes, remaining just as attentive to the dimples in her patient’s cheeks and the gold cross around her neck as to her physical reflexes. If I’d landed in Ofri’s office, I’d have thought I’d found the perfect doctor. Which is exactly the point. Ofri lays on the perfection thick enough that it grates:

Just to show the ER docs how real academic medicine was done, I wrote up an extensive admission note for Mercedes, detailing all the rare causes of aseptic meningitis listed in Harrison’s. Paragraph after paragraph elucidated my clinical logic, a textbook example of orderly scientific thinking. And I printed neatly, so it would be easy for anyone perusing the chart to read.

That last part is fantastic. You can almost see her smirking as she writes. The pettiness of lording even penmanship over those ER bros! She even randomly sends off an extra tube of Mercedes’ cerebrospinal fluid for rare tests, anticipating every possible detail a superior physician might ask if she’d overlooked.

But that superiority is about to come crashing down. In fact, if you didn’t catch it already, Ofri has hidden a flaw in plain sight: she initially diagnosed Mercedes with aseptic meningitis. NOT the Lyme diagnosis she is being lauded for at the beginning of the essay. So an attentive reader will see that her confidence is built on sand. Even if you miss that, Ofri wakes you up soon enough.

The next morning, as Ofri is “dazzling” a crowd with the case during grand rounds, the nurses call her to Mercedes’ room. Ofri’s star patient is a mess:

Mercedes was on the floor with her clothes off, hair askew, babbling incoherently. Her IV had been pulled out and her body was splattered with blood. Completely disoriented, she fought us vociferously as we tried to help her back to bed.

Ofri sheepishly resumes the medication she’d canceled and orders another battery of tests. But there’s nothing new on the CT scan or spinal tap. Mercedes gets transferred, Ofri rotates off the ward, and everyone wonders what the hell happened.

Ofri can’t let it go, so she checks back in with an intern and discovers that the Lyme test (one of those rare tests she’d run with the extra tube of cerebrospinal fluid) came back positive. So now we’re back on the timeline of the opening scene:

Soon everybody was talking about the case of Lyme meningitis in our inner-city hospital. The head of my residency program became interested in the case and suggested I plan a seminar on Lyme disease. I set about obtaining all the details of Mercedes’ case and searched the medical literature for current articles on Lyme disease. Meanwhile, Mercedes was started on the appropriate medication for Lyme. She’d been discharged home and was finishing her three-week course of antibiotics with daily shots in the clinic.

Ofri has already been wrong once. And the Lyme test wasn’t even an educated guess, just a shot in the dark with a spare tube. A lucky break! But Ofri lets it all go to her head.

Residency would be over at the end of next month. I had been here for ten years, from the beginning of medical school, through my PhD and then my residency. Ten years of medical training! But now it was truly paying off. Ten years of the scientific approach to medicine had prepared me for this case. Ten years of emphasis on careful analysis of data – whether of receptor binding assays in the lab, or signs and symptoms in a patient – had taught me how to establish a hypothesis and come to a logical conclusion. This was the academic way that ensured the highest quality medical care.

I didn’t catch this the first time through the essay, but the Lyme diagnosis wasn’t the result of scientific reasoning or careful analysis of data. Ofri’s academic hypothesis and logical conclusion led to aseptic meningitis. Which was wrong. So Ofri builds dissonance into her narrator’s thought process. Her narrator is deluded, and we’re reliving that blindness in real time. The reasoning doesn’t fit the evidence that’s right before our eyes. We might not be able to pinpoint it, but there’s something off about the essay, an undercurrent of unease that Ofri the writer creates but that the narrator doesn’t yet feel.

A skillful writer will engineer these nuances deftly enough that readers don’t see the big twist coming. But the clues have to be there for the essay to hold up under rereading. Otherwise an editor or analytical reader like me will go back to the beginning and say, “Hey, wait a minute! You didn’t earn that big cliffhanger! The pieces don’t add up!”

But “Merced” earned all the acclaim it received. Its design is nearly airtight.

So Ofri takes her victory lap, Mercedes goes home, and Ofri rotates onto the Intensive Care Unit. As before, she is supremely confident: “Just another twelve sick patients on ventilators with arterial lines and Swans. Let ‘em crash, let ‘em code ….I knew I could handle it.”

Ofri is such an overachiever that she thinks about her patients at home, always searching for an angle to improve their care, never really off the clock. One of her patients is recovering from a stroke and she wants to review his latest blood gas numbers before her next shift, so she calls the hospital from her apartment:

I propped my feet up on my couch and tore open a bag of chili-and-lime tortilla chips. One hand dialed the phone while the other plunged into the bag. This was going to be a great month.

I don’t know about you, but I hate listening to people eat while we’re talking on the phone. It’s the height of arrogance, isn’t it? What a jerk!

The resident who picks up is a friend, so Ofri chats him up a bit. He claims she’s never seen anything like the third patient he admitted that night.

“Really,” I said, pulling out a handful of red, powdery chips. “What did you get?”

“It’s a surprise. Something rare. You’ll see on tomorrow’s rounds.”

“Give me a hint,” I said between chomps of chips. “I covered for you on your anniversary last March. You owe me one.”

I pestered him some more, and then he finally relented. In a conspiratorially low voice, to tantalize my curiosity, he said, “Read up on Lyme meningitis for rounds tomorrow.”

The chips and chili turned to sawdust in my mouth.

Yup, you guessed it. That was Mercedes. Only not in the ER this time, in the ICU. And the kicker is that a second Lyme test comes back negative. So that big-shot diagnosis, all the fanfare at the beginning? A bunch of hot air from a false positive.

I’ve summarized enough of the essay by now, so I’ll fast forward through Ofri’s breathtaking finish, how she slinks back to Mercedes’ bedside to find her brain dead, how she sobs in the arms of a hospital chaplain, even in the arms of Mercedes’ loved ones, how the full meaning of merced, the Spanish word for “mercy,” detonates as the haughty doctor grieves “for the death of [her] belief that intellect conquers all.”

Those aren’t spoilers. Read the essay for yourself. It will hold up.

My point is that to achieve this effect, to set up such a devastating fall, Ofri has to turn the volume up on her arrogance early in the essay. The character we see in her reconstruction is not the self she truly was, not completely. The young woman who mistook a false Lyme test for genius was a lot more than her haughtiness, but that was the note Ofri had to amplify to help us feel her dramatic collapse. The pettiness of extra neat penmanship to humiliate those ER slobs. The nonchalance of munching chips on the phone before George bursts her bubble.

I don’t think Ofri saw herself that way then. I don’t even think she saw her younger self as a true snob at the time she wrote the essay. But she needed the narrator to grate on us for the essay to go somewhere, for there to be evidence of growth. So you might say that Ofri had to reinvent herself as a jerk early on to become lovable at the end.

But this is not just a stunt for dramatic effect. Ofri earns my trust because both halves of her narrative arc breed humility. She doesn’t come off well as the bigshot or as the weeping resident. I learn something new from her life about my own: not just to be wary of pride, but to realize that how I seem to myself might not be at all how others experience me.

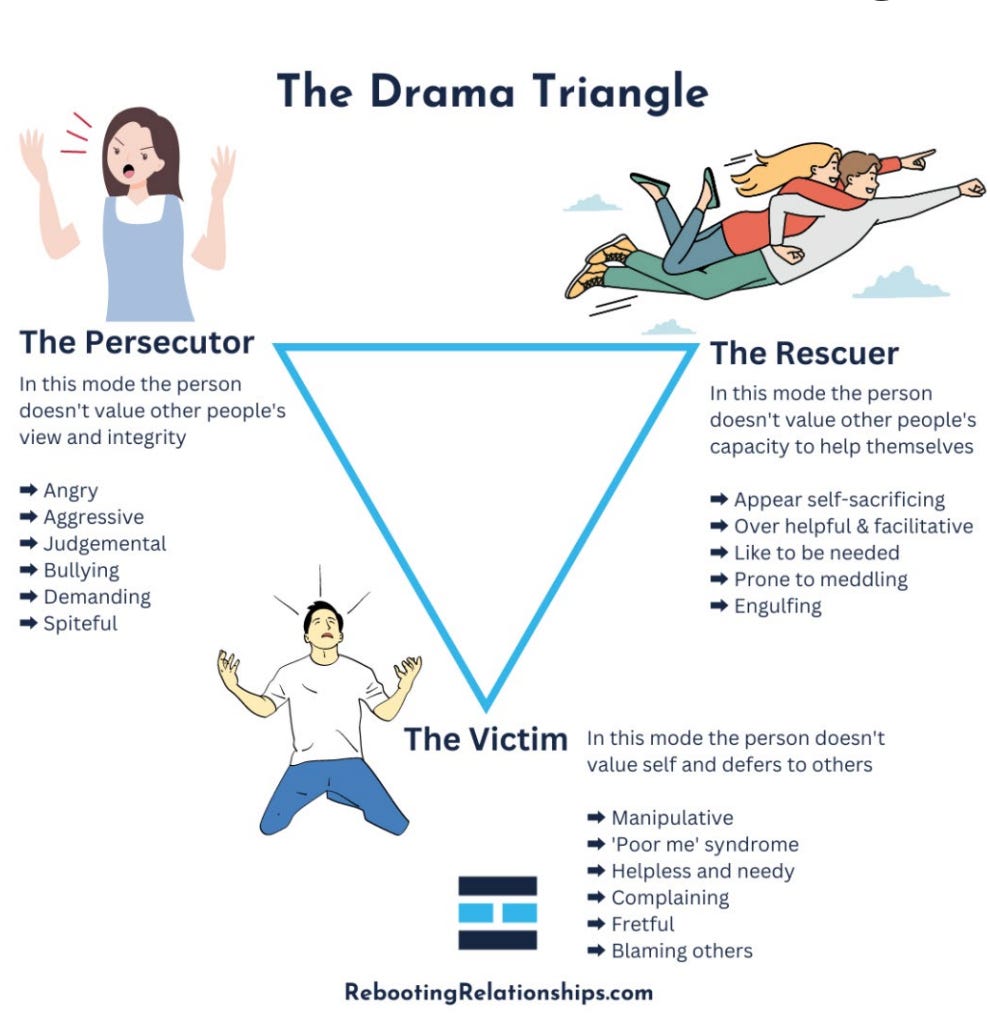

I was thinking about all this while speaking to a client (also a reader of this series) about Karpman’s drama triangle. She was thinking about how to use Karpman’s model in an op-ed that I hope to share with you someday in its public dress. But my thoughts immediately went to memoir.

Karpman’s model identifies a self-fulfilling cycle that traps people in one of three roles: persecutor, victim, and rescuer.2

The drama triangle captures what I dislike about many recent memoirs, not to mention much of my Facebook feed. A lot of new memoirs are not idea-driven, they are identity-driven, and they rehearse these three rigid roles.3 The narrator is the victim or some combination of victim and self-liberator (after having done the work), and the persecutor is the straw man in power. This kind of plot finishes with no growth, or at least not the kind of growth that Ofri models.

In the contemporary memoir, the victim’s liberation turns them into a know-it-all, the very kind of pedant that Ofri is at the outset. But in Ofri’s formulation, the most powerful person is just as capable of transformation as anyone else and the certainties most set in stone are those most likely to crumble. “Merced” moves us beyond the drama triangle altogether into the humble human terrain that more artists ought to occupy, where even humiliation can be a form of mercy.

That’s how you surprise yourself and thereby the reader by writing about a past transformation. In order to show change in yourself, you have to really see yourself in a new way in real time.

Turning yourself into a jerk is just one way to experience new growth while writing about the old.

I’ll have more to say about all this in the weeks ahead, maybe even an essay or two of my own where I practice Ofri’s technique. For now, I’m curious if my hypothesis holds. How well does the drama triangle capture the rhetoric you see on your socials or in any new books that you’ve read?

Read more in the Craft series ⬇️

If that seems like a strange idea — yourself as a character, rather than just as yourself — I recommend my earlier piece, “The Treachery of Narrators in Memoir.” But you shouldn’t need to read it to follow along today.

If I’m not mistaken, these are the three character types that

redefines in his novel, The Requisitions. See our interview for his thoughts on these three types.I think this is also what I find repellant about personal branding. The goal of branding is anathema to personal growth. Rebranding isn’t actually growth, because it’s just another fixed mindset. By contrast, serious memoirists (and other serious artists) are always evolving, perpetually moving targets even to themselves.

Ofri's essay is a great example to illustrate your point about what the narrator needs to do for the reader to feel the intended effect. I agree too many memoirs fall into this interpersonal conflict model, but I wonder how many actually transcend these three stereotypical roles of perp, victim, and savior. I want to see those roles transformed by the end as a reader. The savior role is as problematic as victim and perp.

Thanks for the shout out. I used to be very interested in the Karpman Drama Triangle, not the least because I experienced it personally, and certainly when it comes to writing toxic relationships, it's a damn good structure to base interpersonal conflict on. In "The Requisitions" however, my three characters--at least in their inception--were more based on three 20th century theories about human nature that are clearly note exhaustive but provide a useful framework for characterization: that we tend to pursue pleasure (Sigmund Freud), power (Alfred Adler), or purpose (Viktor Frankl) before we realize we need a balance of all three.