Friends,

I have an interview with Mark Slouka in the works for next week. Today I’m following up a recent piece, “AI and Thou,” with a look at one of the most overlooked medical villains in American literature: Nathaniel Hawthorne’s Roger Chillingworth. A longer version of this essay first appeared in Medical Humanities in 2005.

Josh

Hawthorne Was Right To Fear The Clinical Gaze

Readers of The Scarlet Letter, if they think to mention him at all, regard Hawthorne’s Roger Chillingworth as a Satanic or Faustian figure. He seems like a minor character, notable only for being Hester Prynne’s cuckolded husband and for seeking revenge as her lover’s personal physician, preserving the Reverend Arthur Dimmesdale physically in order to torture him psychologically.

But Chillingworth is more complex than meets the eye. He carries himself with all the coldness of a clinician, yet he commingles science and alchemy and even incorporates herbalism into his medical repertoire after emerging from captivity with an unnamed indigenous tribe.1 In that way, Chillingworth is a historical enigma — a palimpsest, if you like — and each of his layers says something significant about Hawthorne’s view of medicine in the nineteenth century. Indeed, I think Chillingworth’s character is a potent touchstone for our own troubled times.

It’s hard to overstate how thoroughly distrusted scientific physicians were in 1850 when The Scarlet Letter was published. Mary Shelley reflected many of those fears thirty years earlier in Victor Frankenstein, and Hawthorne had already created his most monstrous scientist, Dr. Giacomo Rappaccini, who poisons his own daughter. A rival scholar says of Rappacini: “His patients are interesting to him only as subjects for some new experiment. He would sacrifice human life, his own among the rest, or whatever else was dearest to him, for the sake of adding so much as a grain of mustard-seed to the great heap of his accumulated knowledge.” There’s not much ambiguity in Rappaccini’s character; Hawthorne’s warnings about scientific hubris are sometimes heavy-handed.

There are a lot of Rappaccinis presently promoting AI in medicine, placing more faith in technology than in human connection, and touting efficiency over “I and thou.” Some of them are physicians, some of them are hospital administrators, and some of them are medical insurance executives. Hawthorne’s fears have become our own.

It can be hard to have an honest conversation about the tension between medical science and public fears, particularly when misinformation reigns. You’re not going to get the truth about medicine from New Amsterdam or Dr. Death. Most doctors aren’t heroic single fathers or monsters who sacrifice patients for profit. Substack is no better: reliability isn’t the prevailing metric for leaderboards under Science and Medicine. This is why I find literature a productive space for thinking about the nexus of scientific integrity and the popular imagination. There’s room for ambiguity, complexity, and depth of character in a story — time to reflect on what it means to inhabit both sides of the doctor-patient exchange.

MDs and pre-health majors everywhere should be reading Hawthorne to think more deeply about the doctor-patient relationship, particularly how fallacies like clinical objectivity work against interpersonal trust. Doctors have implicit bias like everyone else, experience positive and negative emotional responses to patients, and sometimes even have to serve a corporate agenda in violation of the Hippocratic Oath.

Hawthorne makes a subtle but audacious claim in The Scarlet Letter: moral compromise is built into medicine. It’s not so easy to separate the personal from the professional. Roger Chillingworth’s personal baggage might be a little extreme, but Hawthorne leverages it to expose clinical objectivity as a fallacy.

Chillingworth arrives in Boston as a stranger “clad in a strange disarray of civilized and savage costume” at the very moment that his wife has been called to the scaffold to be interrogated (she won’t give up her lover’s name) and punished for adultery. From that first glimpse, we understand that he is a man who buries his passions beneath a clinical mask:

At his arrival in the market-place, and some time before she saw him, the stranger had bent his eyes on Hester Prynne. It was carelessly, at first, like a man chiefly accustomed to look inward, and to whom external matters are of little value and import, unless they bear relation to something within his mind. Very soon, however, his look became keen and penetrative. A writhing horror twisted itself across his features, like a snake gliding swiftly over them, and making one little pause, with all its wreathed intervolutions in open sight. His face darkened with some powerful emotion, which, nevertheless, he so instantaneously controlled by an effort of his will, that, save at a single moment, its expression might have passed for calmness. After a brief space, the convulsion grew almost imperceptible, and finally subsided into the depths of his nature.

How should we feel about this? On the one hand, Chillingworth seems human. Anyone would be upset if they’d been separated from their spouse for years and hoped for a happy reunion, only to discover their partner disgraced. And isn’t self-control admirable? But snake-like horror is unsettling — the kind of thing you can’t unsee in a person once it’s revealed.

Despite this foreboding introduction, Hawthorne takes pains to establish Chillingworth’s credentials as a student of Paracelsus, the founder of medical chemistry (“iatrochemistry” if you want to impress someone). Paracelsus dabbled in alchemy and probably died of mercury poisoning, but he was widely recognized for his scientific integrity and genuine medical authority. Paracelsus died in 1541, more than a hundred years before Chillingworth’s time, so knowledge of his methods implies depth of scholarship, access to libraries, elite levels of learning. Chillingworth would have been unusually decorated for a physician in New England at that time. He is portrayed as a master of his craft.2

Chillingworth also shows genuine care at times. He treats Hester in her prison cell after her public shaming and even soothes her daughter Pearl. When Hester suspects that he will poison Pearl out of vengeance, Chillingworth insists that he could offer no better care for a child of his own. He takes Hester’s pulse with “calm and intent scrutiny” and prepares a draught for her that reflects both his European training and indigenous education.

Tension crackles between the two, straining their relationship as doctor and patient, yet Chillingworth remains true to the foremost medical principle of preserving life. This early glimpse of Chillingworth shows his deftness in medical practice, his eloquence, his insight into the human condition, and his ability to control his emotions—all qualities we trust in our own doctors.

But as The Scarlet Letter unfolds, the townspeople suspect Chillingworth of having learned shamanic magic and herbalism during his captivity. Many cultures regard Western medicine as seriously ignorant of herbal cures. In fact, herbalism has often been marginalized in Western medicine precisely because it is associated—fairly or unfairly—with the folk tradition of trial and error, rather than the scientific method of hypothesis and experiment.3

Rumors begin to swirl in Boston that Chillingworth is practicing black magic. An “aged handscraftsman” claims that Chillingworth once collaborated with Dr. Simon Forman, a “famous old conjurer.” Others suspect him of having “join[ed] in the incantations of the savage priests,” as medicine men were “universally acknowledged to be powerful enchanters, often performing seemingly miraculous cures by their skill in the black art.” Such rumors are never proven, but they make a reader wonder whether Chillingworth is a charlatan or a true healer.

Hawthorne’s most damning historical allusion is to Sir Kenelm Digby, whom Chillingworth claims as a scientific acquaintance. Digby is recognized by medical historians as a physician who dabbled in the occult. He was also known to administer “sympathy powder,” a specious folk practice whereby the injured person’s bloody clothing was soaked in powder to alleviate the pain. So some intrigue emerges in the apparent contradiction between Chillingworth’s authority and his association with medical frauds. Is he really just a quack?

It’s probably not shocking that Hawthorne’s fear of physicians stemmed from childhood trauma. He injured his foot so seriously as a boy that he was disabled for over a year as all the local doctors poked and prodded him to no avail. He was also a deeply private person who felt that scientists violated a sacred veil with dissection, just as pseudoscientists did with mesmerism. So the emergence of autopsy in medical education, and the hubris that some physicians exhibited as a result of their knowledge, troubled Hawthorne a great deal.

This was the heyday of clinical medicine in France, where every American physician studied if they could afford it. The clinicians were idealists, utopian thinkers who lost sight of humanity in their quest for God-like knowledge of the body. Michel Foucault describes the clinical eye as “the Gaze that envelops, caresses, details, atomizes the most individual flesh[,] […] that fixed, attentive, rather dilated gaze which, from the height of death, has already condemned life.” Indeed, after studying anatomy in so many corpses, the doctor’s eye became “a great white eye that unties the knot of life.” From his appearance at the scaffold in the opening scenes to the close of the novel, Chillingworth fixes his eye on those around him with just this sort of penetrating and attentive gaze.

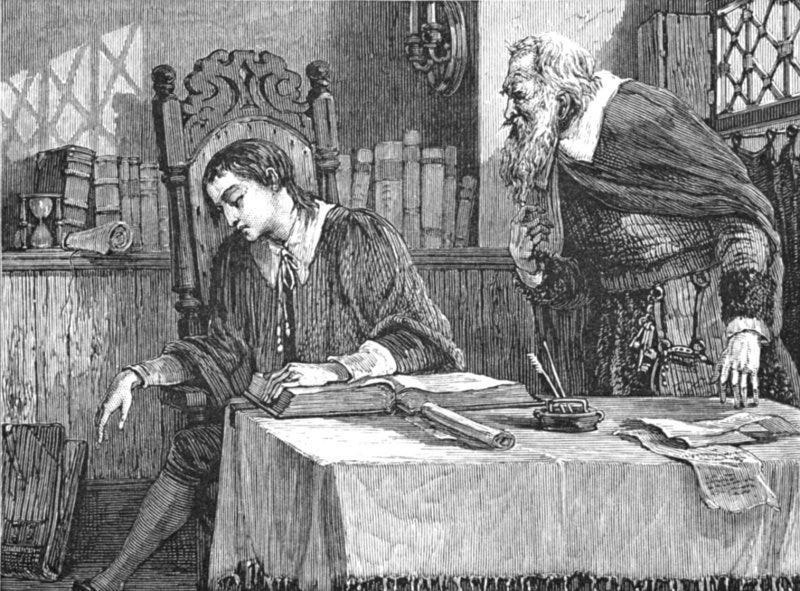

The nineteenth-century public was, per Foucault, “haunted by that absolute eye that cadaverizes life and rediscovers in the corpse the frail, broken nervure of life.” To wit, Chillingworth’s character turns diabolical as his previously stoic powers of observation become tools of premeditated malice. He makes good on his promise to Hester that he will find her partner in crime, following his hunches to Reverend Dimmesdale, whom he befriends and studies with an alarming intensity.

He had begun an investigation, as he imagined, with the severe and equal integrity of a judge, desirous only of truth, even as if the question involved no more than the air-drawn lines and figures of a geometrical problem, instead of human passions, and wrongs inflicted on himself. But, as he proceeded, a terrible fascination, a kind of fierce, though still calm, necessity, seized the old man within its gripe, and never set him free again, until he had done all its bidding. He now dug into the poor clergyman’s heart, like a miner searching for gold; or, rather, like a sexton delving into a grave, possibly in quest of a jewel that had been buried on the dead man’s bosom, but likely to find nothing save mortality and corruption.

Amid Dimmesdale’s “pure sentiments,” Chillingworth “gropes” for an animal nature, stealing about in the minister’s “dim interior” like a thief.

His suspicions are confirmed in a truly remarkable scene, in which Dimmesdale mounts the very scaffold where Hester Prynne once stood, not knowing that Chillingworth has followed him there. The minister’s conscience drives him outdoors in the dead of night, and he stands cloaked in darkness before the town, aching to confess yet unable to do so. Hester and Pearl happen to walk past, as Hester had been visiting the Governor on his deathbed to measure him for a funeral robe. Dimmesdale calls his lover and child to his side, and the three form “an electric chain” as they stand together as a clandestine family.

No one writes scenes like this anymore, but I’m still in awe of it. A meteor flashes across the sky, leaving behind what seems like a red A written across the sky, but could just as easily be Dimmesdale’s guilty projection. The light quickly fades, but not before it reveals Chillingworth standing there.

All the time that [Dimmesdale] gazed upward to the zenith, he was, nevertheless, perfectly aware that little Pearl was pointing her finger towards old Roger Chillingworth, who stood at no great distance from the scaffold. The minister appeared to see him, with the same glance that discerned the miraculous letter. To his features, as to all other objects, the meteoric light imparted a new expression; or it might well be that the physician was not careful then, as at all other times, to hide the malevolence with which he looked upon his victim. Certainly, if the meteor kindled up the sky, and disclosed the earth, with an awfulness that admonished Hester Prynne and the clergyman of the day of judgment, then might Roger Chillingworth have passed with them for the arch-fiend, standing there with a smile and scowl, to claim his own. So vivid was the expression, or so intense the minister’s perception of it, that it seemed still to remain painted on the darkness, after the meteor had vanished, with an effect as if the street and all things else were at once annihilated.

Chillingworth has already been dissecting the minister’s interior life, but up to this point he has not found the proof he seeks. Thereafter, he turns all of his intellectual powers to vengeance.

The most devastating takeaway from Chillingworth’s transformation is that his torture of Dimmesdale flies in the face of his medical training, suggesting that medical science is most dangerous when clinicians refuse to acknowledge their own vulnerability. Such a denial of subjectivity threatens both doctor and patient: Dimmesdale is destroyed by Chillingworth’s dissection of his character, and Chillingworth, himself, is reduced to a parasite.

Chillingworth becomes worse than a phony shaman; he is a truth-seeker who knew better, who had the great story of physical causes at his disposal, as well as the art of persuasion, but chose to use these talents as tools of deception and revenge. Dimmesdale’s death deprives Chillingworth of his host, leaving him with “a blank, dull countenance, out of which the life seemed to have departed.”

Nothing was more remarkable than the change which took place, almost immediately after Mr. Dimmesdale’s death, in the appearance and demeanor of the old man known as Roger Chillingworth. All his strength and energy—all his vital and intellectual force—seemed at once to desert him; insomuch that he positively withered up, shrivelled away, and almost vanished from mortal sight, like an uprooted weed that lies wilting in the sun.

With the freeze-frame of Chillingworth’s final blank expression in mind, we might recall the layers revealed throughout the novel. Behind the flat gaze of that closing scene lies the “great white eye” of nineteenth-century medicine that “unties the knot of life.” Beneath the clinical eye linger traces of herbalism, Chillingworth’s potentially dark secrets: the scandals implicit in Sir Kenelm Digby’s mixture of science and occultism, bad medicine, polypharmacy. Yet further back, before his hair turned grey perhaps, one might catch a glimpse of a young Roger Prynne, the iatrochemist, bent over a Paracelsian text, still the “wise and just man” that Hester once knew, not yet a symbol of the nineteenth-century public’s growing fear of the scientific physician.

The Scarlet Letter remains relevant to our time because it shows that the best methods and the most advanced technologies are only as humane as the caregivers who wield them. I have no wish to return to the Middle Ages or to replace science with mysticism. Every time I visit my local clinic for a routine checkup or outpatient procedure, I encounter good people who are doing their best, within their corporate constraints, to connect with me and show me that they genuinely care. These are the people who take their time, don’t show flickers of annoyance when my questions go on too long. I’m grateful for them.

Yet I also hear echoes of Roger Chillingworth along those corridors. It’s not that anyone is out to avenge themselves on me, it’s the feeling that I, myself, don’t matter much in the great machinery of the place except as a body from which the clinic and insurance company leech what they can for their own bottom lines. I know that “keen and penetrative” gaze, the Rappaccinian fascination with tests (some of which yield dubious results), the hidden curriculum that privileges efficiency over emotional presence.

It’s easy to blame the public for their fears, their ignorance, their wish for the quick fix. But Hawthorne didn’t create Roger Chillingworth out of thin air. His character emerged from hundreds of Hawthorne’s personal interactions, from a visceral sense that science cared infinitely more for knowledge than it did for humankind. He was right to fear the clinical gaze. He just hadn’t learned that scientific medicine could wear a more compassionate face.

Most of the medical characters we see these days in film and streaming TV hew to formulaic types, and as a result they reveal less about public attitudes toward medicine than the literature of the past. But the attacks on medical research, on institutions like the CDC, on historically heroic public health initiatives like vaccines — these attacks tell their own story. I don’t know what it will take to turn the tide, to make people trust scientific medicine again. But I suspect that many people have written their own versions of Roger Chillingworth’s character from their own lived experience. It took time for those feelings to take hold. It will take time for them to change shape.

A friend of mine keeps a rock on his kitchen counter with the simple inscription “Billions.” It stands for the billions of steps it took to create the climate crisis and the billions of steps it will take to walk it back.

The same is true of how doctors come alive in our imaginations.

Further reading

I’m indebted to Stephanie Browner’s “Authorizing the Body: Scientific Medicine and The Scarlet Letter” and to much of Norman Gevitz’s work, including “’The Devil Hath Laughed at the Physicians’: Witchcraft and Medical Practice in Seventeenth-Century New England.”

See also Michel Foucault’s The Birth of the Clinic, Oliver Wendell Holmes’s “Homeopathy and Its Kindred Delusions,” and Edwin Haviland Miller’s Salem Is My Dwelling Place: A Life of Nathaniel Hawthorne.

Read more essays on science and medicine ⬇️

His name is actually Roger Prynne, a fact he conceals with a pseudonym after arriving in Boston to see his wife being publicly shamed for adultery.

Hawthorne’s allusion to Paracelsus is portentous because it distances Chillingworth from the Galenic tradition, which dominated Western medicine for over a thousand years and became the very institution that Paracelsus opposed. This marks Chillingworth as a progressive thinker and an innovator, with the searching mind of the great physician described by Owsei Temkin, who cites philosophy, logic, research, and virtue as hallmarks of medical integrity.

Paracelsus’s Doctrine of Signatures was based largely on folk remedies, and has compromised his reputation in the eyes of some scholars, who believe that his discoveries materialized more by accident than by systematic experimentation.

Excellent article--and interesting how Chillingsworth is both the measured, well-trained physician and the vengeful dabbler in the occult--especially considering the fascination Hawthorne had with witchcraft.

I know folks say, "Are they still teaching The Scarlet Letter?" See Crazy, Stupid Love: great flick, BTW. I still love the novel as clearly you do, Josh!