"I'm not Korean American. But I had to discover that I wasn't white."

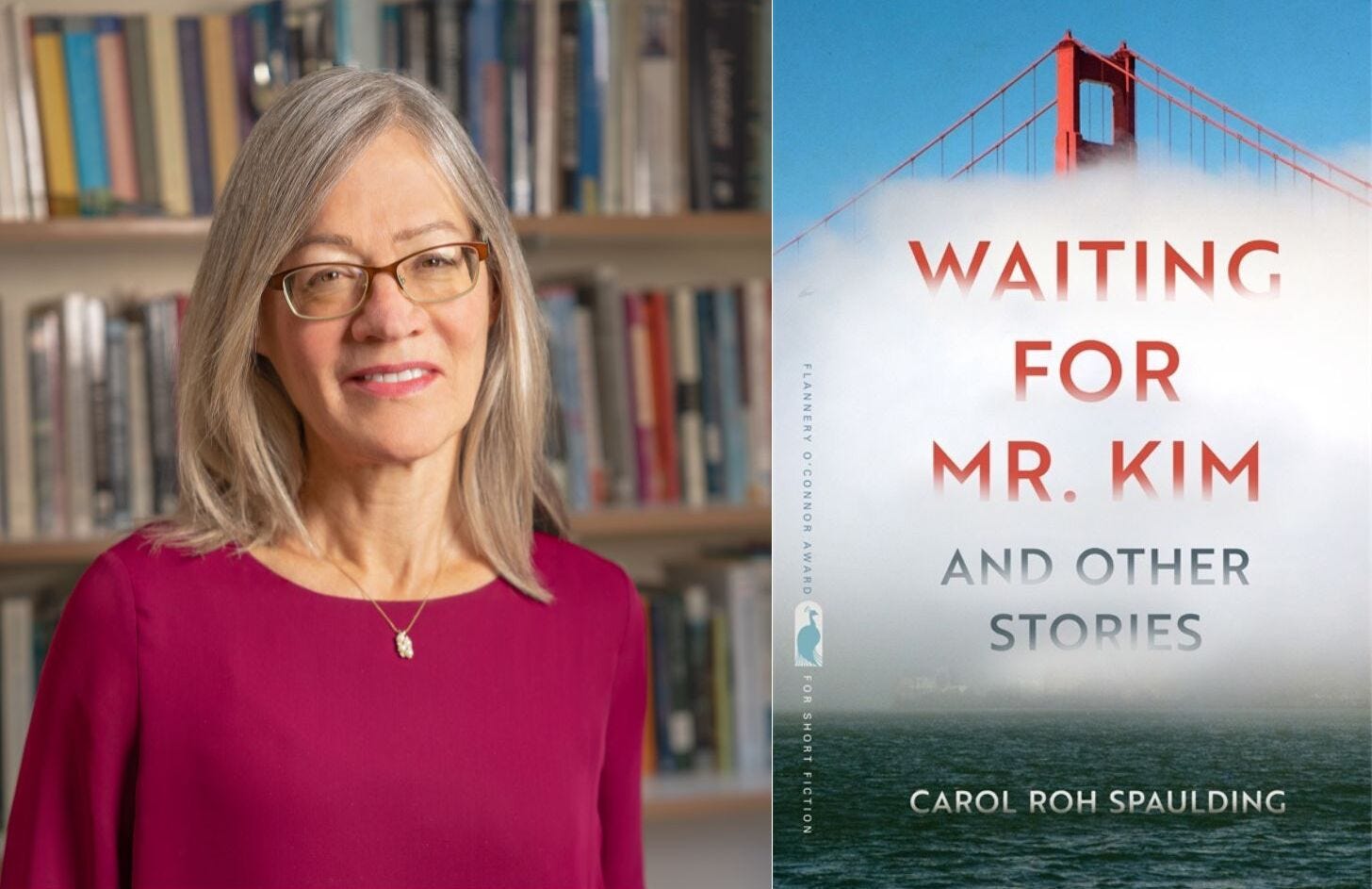

Carol Roh Spaulding on her prizewinning story collection, "Waiting for Mr. Kim and Other Stories"

Today I’m thrilled to introduce you to

, a dear friend and longtime writing collaborator. Carol and I met nearly twelve years ago at a networking event for my college’s service-learning program. Carol had brought one of her students along, and our talk was so intense that the student asked her on the drive back if all professors talked to each other like that. Carol said, “Not often enough.” Since then we have exchanged dozens of drafts, cheering each other on and commiserating about the joys and sorrows of the writing life. I’m so happy to share Carol’s recent success with you.Carol Roh Spaulding is Professor of English and directs the Drake Community Press at Drake University in Des Moines, Iowa. Her collection Waiting for Mr. Kim and Other Stories is the 2022 winner of the Flannery O’Connor Award for Short Fiction and was just released by the University of Georgia Press on September 15. Her forthcoming novel, Helen Button (Sowilo Press, 2024) received the 2021 Eludia Award from Hidden River Arts. In addition to writing fiction, Roh Spaulding is at work on a collection of essays on non-binary concepts across culture, titled The Green Chinese of Africa. Relatedly, her Substack, “Between,” explores alternatives to binary thinking in current events. Her forthcoming Substack, “Convinced,” on contemporary Quaker life, will launch soon. She is also an occasional contributor at the Substack

.Today’s conversation is free to all. For access to many more longform interviews, including conversations with memoirist Kelly J. Baker, activist and coach Sarah Trocchio, and scientist Liz Haswell, please consider upgrading your membership.

A Conversation with Carol Roh Spaulding

Joshua Doležal: Thanks so much for taking time to talk, Carol. I’ve been reading Waiting for Mr. Kim and Other Stories for the past week, slowly, so I can savor it. And I’m so excited to have you here. And just a note before we dive in: people can order your book now on Amazon, Barnes & Noble, and wherever else books are sold?

Carol Roh Spaulding: Yes. And then also just the UGA Press site. But I recommend either asking for it at your public library asking them to order it – or local booksellers that you want to support. But it's pretty easy to obtain.

Joshua Doležal: I'm so excited for you. How long did you work on this manuscript? I think you told me 30 years.

Carol Roh Spaulding: I wrote the first story about 30 years ago. I was early in grad school then, and had just answered a call for a fiction contest at Ploughshares, and it was the first story that I'd ever done, because I was in a literature PhD program.

So I wasn't actively producing stories or even necessarily seeing myself as a writer. I was studying American literature. But I answered the call for that Ploughshares contest at the prompting of a friend. I think it was the last day and I had this story – the first story I'd ever written from my family background. It ended up being “Waiting for Mr. Kim.” I had never written stories like that. I didn't have a sense of myself in any way as an Asian American writer. I was, as Marie Lee put it recently, writing Flannery O'Connor fan fiction at the time.

But this story was based on a little tidbit that my mom had told me years ago. It came to life around that time and I sent it off and it won and it did really well. And I did get inquiries because it ended up winning a Pushcart that year too. So I got inquiries from agents, who would always ask if I had a novel. And no, I did not. And could I turn that story into a novel? I was anxious to get attention, but didn't really have anything to sell, you know? And so that died down. And over the years I just produced more of the stories, but I didn't really think at the beginning that I was writing a collection, not in any way. I was about five stories in before I began to think of it that way.

Joshua Doležal: And this is your debut work of fiction. I know you have a novel coming out soon as well. So all of this came together very rapidly for you because we've been writing colleagues for several years. And I know that you've been shopping around manuscripts and have an agent, but you couldn't sell your novel for the longest time. And so this has been a long period of frustration for you. This is the first real breakthrough of your writing career. Is that fair to say?

Carol Roh Spaulding: I'm 60. So, yeah. It's not like all I did was hold my breath and wait till I could get published. I'm a scholar, and my areas are multicultural literature and community writing. And I'm also a small press publisher of a community press that I direct, and an active teacher and the parent of a special needs child. So I have a lot going on and always have. I always just stay persistent, but it wasn't like my one thing.

Joshua Doležal: How many contests do you think you've submitted to over 30 years of aspiring to your first book?

Carol Roh Spaulding: Well, when I had about four or five stories, I started thinking along those lines. But I didn't start submitting to contests until I had enough stories and five stories isn't enough. I don't know, let's see. The latest story, the last one written, would have been the last one, the novella, and I'm going to say that was 10 years ago. As a collection, I sent it out probably to at least seven contests.

And I would try different configurations because there's actually a novella that begins the book that obviously isn't in this collection. And then there's a novella that ends the book. So it was very awkward to have those two novellas and then a collection of stories in between.

I would try different configurations of these two novellas and then the five or six stories in between. And finally, with UGA Press, I added a story that I had never seen as being part of the collection, which is the one called “Made You Look.”

And once I added that one, and then the novella at the end, that was the magic combination.

Joshua Doležal: I know so much of being a writer for me is a humbling process of doing my best to hone my craft and trusting my sensibilities, but also paying attention to feedback. Sometimes you can't plan your own design well enough. You were getting feedback all along this process of what maybe wasn't working in the design of the collection and you couldn't just on your own foresee all of that. There is a necessary feedback loop, I guess, from readers or publishers as part of that process.

Carol Roh Spaulding: The main thing that wasn't working was the fact that it wasn't a novel. And, you know I made a last attempt with my agent. She accepted the fact that it wasn't going to be a novel. But that it would be a novel-in-stories is what we were trying to call it. And so she was trying to have me do things that would make it more sellable in that regard. And then started asking for some things that I felt were trying to sell Asian American-ness in ways that didn't, that I just couldn't — I couldn't do that. And so I ended up just not working on it with her anymore.

Joshua Doležal: What was she pushing you to do?

Carol Roh Spaulding: Things like, well, and this is fair. If it was going to have been a novel, then the ghost story that happens in the second story in the book, she wanted that to become more central to the book as a whole. Maybe have the ghost come in at the end and that kind of thing. That is what readers are looking for in a novel. And I understand that. So I didn't want to do it, but it was fair. But there were also some things, like “I have a friend who eats this food and can you get some of this food in or this mention of this symbolism?” or whatever.

And I don't know about that kind of thing, much less want to include it, because it will fulfill people's expectations of what an Asian American book should be. I just wasn't going to go there. No offense to her. Her job is to sell books and she's going to do what she thinks is going to sell books, you know?

Joshua Doležal: There is a window now for stories about identity and race. And in some ways that might've opened up your big break, but you resisted that, so it delayed the publication of this project a bit. Is there anything more you want to say about that the bigger publishing landscape on identity and race?

Carol Roh Spaulding: Well, I mean, first of all the stories were winning awards all along the way: Glimmer Train Fiction Open, Ploughshares, a Pushcart, the Katherine Anne Porter Prize from Nimrod International… Secondly, I'm astounded that the stories still have relevance because they are old stories. And I can't believe that they have survived the test of time.

Now everyone wants books about identity and Asian Americans, but as a scholar I began my graduate career in the first wave of ethnic literature. So it seems very old to me. I read a ton of ethnic American books to do my dissertation. That work had a whole generation long before what people see now as the current identity-focused novel or generation.

Did I get a break because it's an Asian American book? Well, what about Amy Tan, 25, 30 years ago? You can name a lot of Asian American writers along the way. So I don't know the answer to that. I was having a conversation with Lan Samantha Chang last year when her book came out and she did say, because her book, The Family Chao, depicts an Asian American family in a Midwestern town, and she makes some very real, whole characters that give a glimpse into the full humanity of Asian Americans. And she said something about how she had started the book long ago, when people just weren’t ready for it. In this Asian American moment, people are much more ready.

Joshua Doležal: I came of age as a scholar also trained in multicultural criticism, reading works like Leslie Marmon Silko’s Ceremony and just thinking of those as canonical works. I didn't really have a sense of a dead white male canon. At least 20th century American literature was by definition diverse — Toni Morrison and James Baldwin and we could go on. So you're right. There have been different waves and maybe it's never stopped. That's a good point.

But I'd like to dive into your stunning collection. It's just so beautiful. And I was reading it slowly on purpose because I didn't want to skim. It's a delight to read sentences that are so well crafted and just linger and ponder some of those scenes that are so haunting. But I wonder before we dive in, could you give the dust jacket summary, the highlights of this collection, and the arc that it follows?

Carol Roh Spaulding: Yeah, so basically it spans about a century and touches on four generations of a Korean American family in the Bay Area starting with the matriarch. It does tell stories in different voices, including the voice of a ghost who died as a baby, but most of the stories center on Grace Song, whom we meet as a teenager, and then they follow her to her senior citizen age and a love affair that she has as an older woman when she thought that all of that was behind her. So a lot of the stories center on Grace as the moral center of the book.

And what's fun about them as a collection is that they jump through eras that the stories are designed to fit. So you see the fifties in the Beatnik era of San Francisco. And then you jump to the sixties and the seventies. And each time the flavor of the story is trying to capture the essence of that era.

Joshua Doležal: Yeah, that's fun. Well, I picked that up and was really taken by it, but just the sheer scale of change in Grace's life from her childhood when she's contemplating this terrifying arranged marriage, how she can resist that or escape these two older bachelors that are suitors, I guess. And then in the 1970s, suddenly, she's married as a mother. But it's in this community where divorces are common and then there are even things like goodbye ceremonies to celebrate a divorce. It's just such a radical leap from the arranged marriage to that – it's dizzying, the scale of change, but I guess that California has been a crucible of innovation and change.

So would you say that's pretty true of the place where it's set, as well as with America, more generally?

Carol Roh Spaulding: I appreciate the question and the noticing implied in that question because it brings a new thought to me, which is that one of the things that we can really admire about Grace and about a lot of immigrant families is the enormous amount of change that they adapt to over the course of a lifetime. So when my mom turned 80, we went out to California to have a big birthday party for her. And my husband and I were staying on Alameda, which is an island right off the coast there, right off the shore. And to get to Alameda, you have to go through this tunnel. And it turns out that that tunnel passes the very street where my mom grew up, which is the setting for the book. She grew up next to what is now a homeless encampment. There was a Salvation Army and they had a little laundromat and we passed that street and I realized that my mom is from the ‘hood and it just astounded me to think about how far she came. Because she did go to UC Berkeley. She insisted on going. And then she moved with my dad to suburban white Fresno.

A lot of people adapted to enormous change between the 50s and the 60s and the 70s. We were all doing it, but her starting point as a daughter of immigrants who did not speak English was far vaster than it might have been for regions in the country where the pace of change was slower or for people who were born to mainstream culture, and it just astounds me the adjustments that immigrants and immigrant families make.

Joshua Doležal: You're leading me to another question, which is how much of this is autobiographical, and it sounds like Grace is modeled more after your mother. Some of the coming of age stories sound more like they're drawn from your experience, so is it fair to say that Grace is a composite of you and your mother, or is there a different way of thinking about her?

Carol Roh Spaulding: The point of the collection for me was that I was trying to write my way into an understanding or a disposition towards my Korean side. I'm not Korean American. But I had to discover that I wasn't white based on the way people reacted to me. And so I had a very complicated racial formation. And my mom would not talk about her past, which is typical of Asian Americans, because there's a lot of shame and silence around the past. And I think the diasporic experience is also one that tends towards silence. And just chasms of understanding between generations.

But what she did do — because I was trying to be this white kid in Fresno – was she would drop these little hints, and one of them was that when she was 14, she was betrothed to an elderly bachelor. And another was that she had a baby sister who died of rat poisoning. But she never gave me the details or I didn't ask her. So she deployed these moments that became in my imagination just ways to write my way into understanding my Asian side.

“Made You Look” is fairly autobiographical. It’s a memoir for every woman who was a teenager in the 70s. Most of the responses I get is that people really recognize themselves in that story, even though Evie is dealing with other things because she's a racialized body and she's wondering about racialized bodies and sexuality, but at the same time it's a pretty familiar thing for women who grew up in the 70s, too.

Joshua Doležal: I would say men, too. I had the same experience discovering pornographic magazines around someone's house. Obviously, it's different for a woman to be thinking about how they fit into that picture of sexual identity or intimacy or pleasure or whatever it is, but I think it’s more universal.

Carol Roh Spaulding: You write about it, too. I remember from your memoir about your discovery and, yeah, there's similar passages in some ways of that apprehension of this whole world.

Joshua Doležal: I was lifting weights in the attic of a neighbor's house, and he was from the Bay Area and had brought all this literature with him to Montana, and it was certainly not something I was exposed to in my sheltered Pentecostal upbringing. That was in the 90s, so different time period, but I think a universal story of awakening. But I want to circle back, and forgive me for hovering over this, but you'd said your agent characterized the collection as a novel-in-essays, so you've anticipated one of my questions.

Memoir-in-essays is en vogue now. It used to be that nobody wanted to publish essay collections. I guess people still don't, but if you can call it a memoir-in-essays, there's a loose thread that connects everything that is apparently attractive now. Joan Frank, one of your reviewers, refers to your book as a linked collection.

But I was thinking that some could call it auto fiction. That's where I was going with the question about how much was autobiographical. And there are some real affinities with the Bildungsroman form of the novel. So how do you speak of the collection? What genre do you classify it in, or what label do you give it?

Carol Roh Spaulding: It's technically a story cycle, which is a linked collection that you often find in multicultural literature. Louise Erdrich's Love Medicine, Don Lee's collection Yellow, even The Woman Warrior in some ways. A story cycle is a collection that is able to accommodate the diasporic experience, where you have different members of different generations from the same family relating their experience. The collection as a whole is restorative of the loss of communication that happens between generations. And so in my collection the characters in the final story, like the grandson — he doesn't know his great grandfather and he has no concept of how his great grandfather's experience is related to his and so the people in the story don't necessarily see any cultural or historical or even familial ties, but readers are invited to ponder what those ties might be. So it has this restorative element that works well for immigrant literature. And it's so sad that I couldn't include the original story because the first story is my favorite story of all time. I absolutely love it, but it's a novella, so it wouldn't have fit.

And it tells the story of the father, Song, coming to the mainland. He emigrates in 1903, and he's a fruit picker in Hawaii, and then he comes to the mainland and becomes a fruit picker here. And he actually ends up working for the grandfather of the man who will end up being his son-in-law. And so later he's doing migrant farm work on a piece of land that ends up being the land that is deeded to the Song family later on. And he's picking the fruit that is owned by the man who will end up being his relation, his in-law. And neither of them could possibly imagine that their children would intermarry in a generation. So that story really brings the book full circle. My dream is that one day they could all be in the same collection.

Joshua Doležal: How interesting that the first story you started back in the 90s isn't actually the point of entry for this collection. Instead, we have “Day of the Swallows, 1924.” It's hard to talk about this book in a way because it shifts. You can't just talk about Grace because Grace is not the speaker in “Day of the Swallows, 1924.” So why did you begin the collection there? It sounds like you would prefer to begin the collection with the father's story. But who's speaking in “Day of the Swallows,” and why does that provide the entry point for Waiting for Mr. Kim?

Carol Roh Spaulding: The mother. It is Grace's mother speaking in “Day of the Swallows.” And the year is important because she has been in the country for one year and had she come later, she wouldn't have been able to enter at all because of the Great Immigration Act of 1924, which would have cut off entry by all Asians until 1965. So she just makes it in and she's now stuck here and she doesn't like it. And her beginning as an immigrant in this country is a very unhappy one, and she feels terribly displaced and stuck and somewhat alone. And that casts a pallor over the book in a way.

There's a Korean concept of Han, which is this permanently inconsolable sense of loss that arises from their history as a colonized people and conquered people over many centuries. And she certainly is exhibiting that sense of Han, even though I don't use the word in the book. One could say that there is a sense of that throughout the book. So sometimes you hear about an elegiac tone that tends to overtake books from Asian Americans. And I think some of it is that there is this history of longing, sadness, and irreconcilable kinds of differences between being Asian and being a robust, enthusiastic, individualistic American and that hovers there, and so she gives that characteristic early on in the story, and I wanted to give her a voice because she doesn't really feature much in the rest of the book.

And when she does, it isn't a very likable portrayal.

“Today, as they do every year, swallows alight in Pusan, in Pyongyang, in Seoul, on Chejudo. Today I became an exile. The Immigration Act has sealed the borders indefinitely to everyone on the globe. Those who are in the United States cannot get back with any reasonable expectation of reentry. If you left a wife behind, too bad. If you hoped your family might join you, think again. It is over for you, over for them, those days.”

From “Day of the Swallows, 1924”

Joshua Doležal: As you're speaking about Han, I think of it as germane to so many immigrant stories. I mean, there's some version of Han in my Czech family history as well. The Czechs also are colonized people for many centuries. So many people coming to the U.S. as refugees would resonate with that idea, and others speak of this as a form of inherited trauma, that generations feel the echo of Han. And so, as you say, it's not explicitly tackled in later chapters, but it's there as a framing device for the collection.

So then the next chapter, “A Former Citizen,” as you've already said, is inspired by real events. What inspired that story and why did you place it so near the beginning? Who's speaking in this story, and how does it fit as part of what frames Grace's narrative?

Carol Roh Spaulding: There are some very practical considerations, which is that the family is establishing itself and really lucks out in a couple of ways. They are only able to own property because of the Japanese American internment, for example. So the family lucks into being able to purchase this bathhouse laundromat combination and make their way in the world because of the misfortune of another Asian population.

And so they're able to gain property and eventually citizenship. This is a very big deal. So if you're talking about a trajectory over the century there's got to be a story about how you establish yourself, how you become a citizen, and what that process looks like for an Asian American family.

It's there early in the narrative just because showing four generations means you show how they get established. And then I also like the idea that this ghost narrator is able to look across the span of time. I like that she can because she's a ghost, she can look forward and backward. At least my ghost can. I feel like she looks out over the span of the stories and encompasses them all in a way. And we have a sense that what's coming is an enormous amount of change because she prefigures that a little bit in some of the things she says, and an enormous amount of sadness as well. So I just like that there is, I don't know, an oracle or something bigger.

“Death is a birthday. There are many variations, but I can assure you there is nothing to fear. Your blood will probably begin to sing – a high, urgent whistling through your veins. Your mouth will have a funny taste and feel, as though you have eaten something furry and rotten. For a short time, your stomach might hurt, an acidic jolt, or possibly a dull throbbing, or your head might feel as though it is floating up and up. You will lie down so that you can watch this happen, and the ceiling will retreat, leaving you gasping beneath the quiet stars. Rising, you will try to follow the most silent and distant star of all, to nestle into its cold neck. But it will pull and suck at your lungs, asking to do your breathing for you. You will give yourself over to it. This part is uncomfortable but does not last for long. Then the bad taste in your mouth becomes a numbing sweetness.”

From “A Former Citizen”

Joshua Doležal: Well, tell me if I'm wrong about this, but one way I was making sense of the story collection, because there's so many shifting points of view. It's not a linked collection in the sense that Grace is the speaker of every story. Her mother is the speaker of the first chapter, and then her dead sister is the speaker of the next one, and then she's referred to in the third person in “White Fate 1959.” But in “Typesetting, 1964” and in “Do Us Part, 1973,” she becomes the first person speaker.

What I'm imagining is this development of a character that coincides with our own psychological development, that we don't have a conscious awareness of self when we're babies, that we become aware early in our toddlerhood of ourselves as autonomous beings. But then we don't really have that sense of agency or independent voice – part of coming of age is finding that. So I don't know if you meant it to work that way, but as I read the story, by the time Grace is a young adult and a mother, that's when the first person point of view comes in, and the earlier formative parts of her story, she doesn't have a voice in, really. Is that intentional?

Carol Roh Spaulding: No, not at all, but I like it. We'll go with that. The first story told from her point of view is “Waiting for Mr. Kim,” which is the third story in the book, but it is told in the third person. And then that is followed by “White Fate.” And that story is important because it's told from the point of view of her father.

And my mom was incredibly close to her dad, whom I never met. And I just wanted to try to imagine what it must have been like for him to be poised at the end of his life and at the dawn of extreme change, including the change in his own family. I had to write a story that tried to imagine what he was like and what it felt like to be him, even though it's incredibly presumptuous for me to have done so. I rode on my mother's love for him as a way to try to understand, or I felt like my mother's love for him was my license.

So that’s a love story, “White Fate,” is a love letter to my grandfather. And then, yes, “Typesetting” is where we first get Grace in the first person. She has come of age, she has come into her own.

“Whitecaps scudded along the surface of the bay. Across the water rose the green coastal mountains of Marin with its hushed forests of ancient redwoods. He stayed up there just a minute or two and talked to his daughter in the serious way that people talk to infants when they are alone with them. He pointed across the water and told her about a place that he had once called home… This tiny person! He could not begin to imagine her fate. But here, just for this moment, he was never going to let go of her, this child for whom the whole world was nothing but a tightly wrapped cloth and his beating heart and, above it all, this wild blue.”

From “White Fate, 1959”

Joshua Doležal: And then after “Do Us Part, 1973,” we get “Made You Look,” which is 1979. Grace is married and a mother in 1973. “Made You Look” moves forward in time, but it features a different first person narrator, Evie, a teenage girl who is just becoming aware of her sexuality, as we were saying, partly because of finding Hustler magazines and things around people's houses.

Why is that not Grace's story? Why is it Evie's story? Grace has leapfrogged her sexual coming of age, because she's already in a relationship in “Typesetting.” Why do we have a different character there, later in time?

Carol Roh Spaulding: So the character is her daughter, who is now a teenager. And so you're asking why is it not Grace's story instead of Evie's story?

Joshua Doležal: Well, I'm just wondering why we get it from Evie's perspective when this would have been also part of Grace's rapidly fluctuating world from the point where she had no agency in this arranged marriage to that fluid world where even marriage covenants are not forever. She would have had a similar awakening to Evie's. So it's a gap in Grace's story.

Carol Roh Spaulding: There is a book logic to it, which is that Grace turns off in terms of her sexual awakening. And so you can see that when she's talking with Daro [in the final story] and is very reluctant to begin a love affair. That side of her has long been over and it takes quite a bit for it to be resurrected. I think a lot of women would see in that as a mother of three kids and she has a failing marriage and she has this temperamental daughter and all of this stuff going on, that that side of her just goes dormant for a while and she expects that it will always be that way.

And I think it's not uncommon for mothers and daughters to have a situation where their daughters inhabit or manifest a dormant sexuality that they themselves couldn't express. I'm not saying that that's what I planned, but I think because Grace is such a reluctant lover in the last story, it does make sense that Evie takes over in terms of point of view for a while.

Joshua Doležal: You're reminding me of a completely failed experiment in one of my American Lit classes where I was trying to examine the shift between second wave feminism as embodied by Sharon Olds, who I think is very much in tune with Evie. Some people have crassly said that second wave feminism is, “I can have sex like a man,” which is reductive and inaccurate, but captures this idea that women have sexual hunger too, whereas third wave feminism has often focused on things like consent that make sex seem incredibly dangerous and perpetually loaded with legal implications. As you said, these stories have been with you for a long time and the world has changed around them. So I don't know how you think about the present day context of sexuality, how we speak about things like desire and consent and Evie’s story, if you're willing to speak about that.

Carol Roh Spaulding: Well, just that it's complicated and it's fucked up. I mean, my stories aren't messages, right? If they resonate in certain ways, that's great but I certainly didn't write them with any message in mind because I'm very driven by the characters themselves. And I think I've already heard that a lot of women do see themselves in these portrayals because they are complex. If you think about Grace, for example, if you look at “Do Us Part,” you realize things could have gone a different way. Like Wayne has his own baggage and just if he had been able to maybe rise to the occasion of the intimacy that they had broached, maybe things would have been different. Or if Grace had been more assertive or a little less hesitant about things, it's like they just missed it. She goes dormant for a while and just finishes raising her kids and decides to just be this little old lady and so forth. And then that gets unearthed again by a man who doesn't fit the Asian American male stereotype at all. He doesn't come roaring in like Bruce Lee. He's not Bruce Lee because Bruce Lee is stuck in a binary stereotype as well. He is just completely his own person. And not in any way emasculated, but not in any way hyper sexualized or masculine either.

Joshua Doležal: So fascinating. The end of the book is this novella, “The Inside of the World, 1997.” It takes up basically half the collection. It's about 100 pages long or a little less than that. And so we can't hit all the high points of it, but it ends with Grace going back to Korea, reversing the immigration narrative that the collection begins with. And it sounds like Grace at this stage is still mirroring much of your mother's experience or what you imagine of it. I don't know if her return to Korea is also driven in part by your own figurative or literal connections to ancestry, but I'm curious what you hope this ending might illuminate, which layers of your life you’re reflecting in it?

Carol Roh Spaulding: I love that question. It makes more sense with the original novella, I will say that. But if you look in “Day of the Swallows,” you see that at one point the mother is pondering the shipwreck of Captain Hendrick Hamel, who was a Dutch sailor whose boat capsized during a storm and 35 men washed to shore on Jeju Island, which is at the southern tip of what is now South Korea. And so she's contemplating this shipwreck because he is an exile and she feels like an exile. She imagines Captain Hamel floating on a piece of ship siding towards the shore. What is going to be his fate? Because the king didn't let them leave. It was a hermit kingdom and they weren't allowed to leave.

At the very end of the book, that story is evoked again. It's a real story. There is a young Korean girl who is looking out and and seeing Captain Hamel coming to shore. And she is the one who gets the last word in the book. And what I hope to imply is that this is a story of a family with a lot of mixtures. This young woman, she's planning for their arrival. What I want to imply is that mixture of cultures is ongoing. It happened 400 years ago, and it continues to happen in the marriage between Grace and Wayne and so forth and then their grandson. This cultural mixing, including the mixing of readers coming to this book to learn about Korean American experience, should be a never-ending project. But that's pretty subtle. I don't know if anyone would pick up on that, but that image does bookend the collection.

Joshua Doležal: You began writing some of these stories as a way of trying to decide what it was to be Korean American, trying to imagine your mother's experience. The whole book is a homecoming that parallels that arc at the end, which is really lovely. I want to circle back to the prize, though, because this was such a big breakthrough for you.

How did you get the news? Where were you? What did you do? What was going through your mind when you learned that you'd won this award and that you would have a book?

Carol Roh Spaulding: It must have been in August. I just found out by email – Lori, my editor, wrote me, and then we arranged for a phone call. I do remember that day it was a beautiful late August or early September afternoon, and I went out back and wandered around in circles for a long time, just stunned. I felt like I had won the Pulitzer Prize or something. It was fun. It was just pure joy.

Hi Joshua, I love your new email header, with context and links to popular posts, and how your homepage is organised. Nice one.