Man Plans, But God Laughs: My WIP 6 Months In

Most of my content in 2025 is free, but I appreciate the support of readers who make my writing life possible. Upgrading your subscription unlocks monthly essays from a memoir-in-progress, as well as the entire archive. I’m also proud to be a Give Back Stack. 5% of my earnings in Q3 will go to the State College Food Bank.

See my accountability page, with receipts for Q1 and Q2, here.

Man Plans, But God Laughs: My WIP 6 Months In

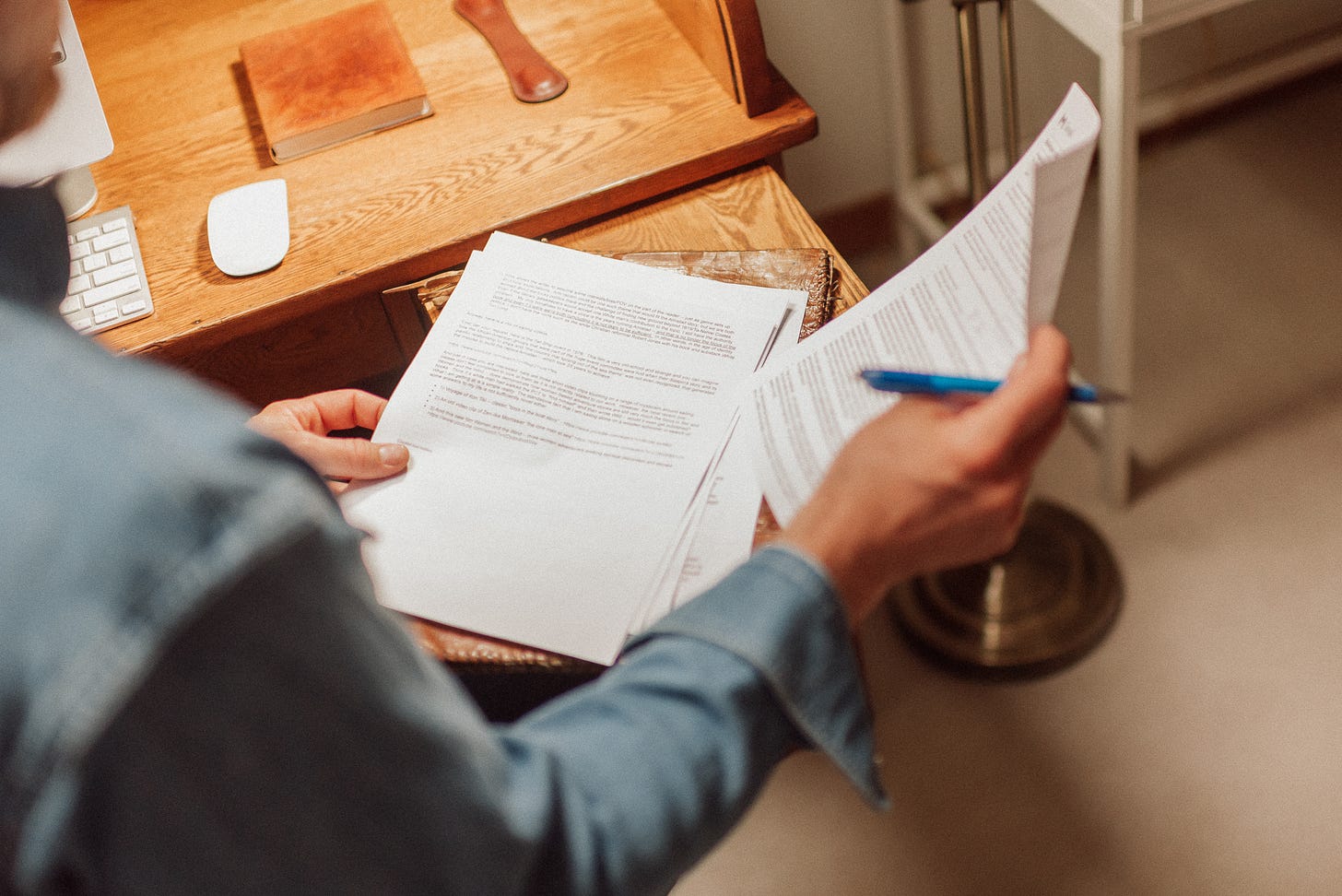

I don’t write anything but poems and songs longhand anymore, so most of my messy manuscripts stay hidden on my hard drive. But since we’re now more than halfway through the year, and I promised to anchor my 2025 series in my fatherhood memoir, it seems only fair to give you a glimpse of what that book looks like now. Just so you don’t think I make promises I can’t keep.

The year began with the same kind of planning that helped me draft a novel in two months, the Mountaineer’s Method for Book Mapping that has helped many of my clients find the core of their stories. But a lot has happened to me this year. After growing up evangelical and turning atheist for twenty years, I’m shockingly (most of all to myself) finding my way back to belief. Among other things, this has made me to think differently about how to frame my childhood, how to write ethically about others, and whether my fatherhood story needs to be centered so firmly on me.

So it’s fair to say that by now I’ve jettisoned the original plan.

I didn’t have a map at all for my first book, just a vague sense that I couldn’t go on writing elegiac essays about the West forever. That meant trying to make peace with Iowa as home, really embracing the prairie. (Judge for yourself by reading the book).

Writing that memoir meant wrestling with conflicts in real time. I’d drafted the ending just a few months before I received an offer from the University of Iowa Press. That contract came the very day my ex and I returned home from the hospital with our first child. In fact, starting a family seemed like the answer to my exile from Montana. Where else do we belong but at our own hearthside, by our own baby’s cradle?

So the close of the book mirrored my life up to the point of publication.

The problem was that I had no idea what the ending would be when I started writing essays in Ted Kooser’s nonfiction seminar ten years earlier. So reviewers who felt that it read more like an essay collection than a continuous story were right — I built that airplane, as they say, while I was flying it.

I was determined to do better this time. Less pantsing. More planning. More charting the long arcs and throughlines.

I’m not sure why I thought I could superimpose a map over my fatherhood arc the very year that my eldest would officially become a teenager, and just one year removed from a messy divorce. That seems hubristic in hindsight, the very definition of Mann Tracht Und Gott Lacht.1 Sometimes I feel like I understand my path well. But most of the time I’m fathering blind, knocking my shins on sharp corners in the dark and cursing my own dumb mistakes.

So I’ve reverted, humbly, to the same method that I used to write my first memoir, which I can only describe as waiting for problems to present themselves then writing my way through them, trying to discover something new. I have no idea how this story will end, how to bring it to any kind of satisfying close.

There’s a loose conflict underneath it all, but I’m not sure I’ve defined it clearly enough, even for myself. Am I trying to convince myself (and others) that I’m a good father by reclaiming my parenting story after so many years of criticism and complaint, both at home and in public discourse about marriage?2 Is my purpose, instead, to interrogate the social conditioning that makes many men feel unprepared to be fathers and that makes professional men and women feel trapped between two impossible sets of expectations? Or is the book that wants to be written more of a love song to my children, a prayer of gratitude in a time of mass discontent?

I’m still figuring that out, but I thought I’d show you the mess by linking to all of the essays that I think might make it into the book in some way. Many of these will be paywalled, since I’ve saved new essays for full members this year. But you’ll find plenty of free pieces, too, from the archive.

I’d love to hear your thoughts on the core of the book, if you’ve been following this project for long. What kind of thread(s) do you see emerging? If you were giving me my own advice about mapping, what design(s) do you see? Essays/chapters are organized loosely by the three sections from my original book map (before fatherhood, married fatherhood, single fatherhood). But I might ditch the linear map entirely in favor of a circular one.

For now, I’m not planning at all. Just writing through the questions and tensions that fatherhood poses for me.

Origins (before fatherhood)

Fathering while married

Fathering Solo

A Yiddish proverb that translates from the German as “Man Plans and God Laughs.” I first heard a variation of it in “Deadwood,” when Al Swearengen says, “Announcing your plans is a good way to hear God laugh.”

I really try to avoid this kind of thing, because it makes me crazy, but I was weak and read Jean Garnett’s “The Trouble With Wanting Men” a few weeks ago. In brief, it’s another complaint — that men don’t seem capable of committing anymore, that they’re always chickening out of partnerships with more emotionally mature women — and ultimately about the angst of wanting men who are all overgrown children, only less sexually confident than they once were. This by an author whose open marriage was apparently not as progressive as she thought, since polyamory led to divorce. And I keep hearing between the lines of her essay the desire for something pretty traditional: a guy who knows the kind of woman he wants and isn’t afraid to chase her. But then she writes gems such as “It must be mildly embarrassing to be a straight man, and it is incumbent upon each of them to mitigate this embarrassment in a way that feels authentic to him.” Which makes me want to quote Ruby Thewes, from Cold Mountain: "Every piece of this is…bullshit. They call this war a cloud over the land, but they made the weather and then they stand in the rain and say, ‘Shit, it's rainin'!’” But this kind of reasoning leads nowhere productive, and I decided long ago that I wouldn’t let it poison my book. So, lucky you, here it is in a footnote! (Sometimes I have to check to see if you’re paying attention 😂)

I’ve read bits of your memoir over the months, and enjoyed it.

I think your kids might one day enjoy reading about your hopes for each of them, and the sparks of spirit within each that you gently nurture. (And how you do this)

Also, each will reach a point in their life where they will want to know what you love about them and why. These are the things my daughters ask me now that they are older.

The journey to becoming a whole human hopefully leads to self-actualization. Personal growth toward loving ourselves as we are, where we are physically and spiritually. It includes appreciating and finding love for others as they are, where they are on their own journey.

In your digression above, it doesn't seem as though the author has found peace with her own part in a relationship. We shouldn't have to chase or search if we know the love within ourselves. Women, nor men, need to be conquered. When we love ourselves and give light from within, we can better see and love the amazing person standing right in front of us for who they are at that moment.

I enjoy a linear story and progression and might agree that the second half of your memoir read to me like a compilation of essays. However, it seems with this memoir that you are trying to draw more meaningful conclusions perhaps about why we parent/father the way we do? In recent chapters it seems you are attempting a more circular connection of how to be grateful for our past as it helped define who we are in the present; therefore, having this perspective may help you love your children for who they are as an individual, on their own path, in their own in time. Maybe revising some of your earlier pieces to reflect this growth in perspective would help the essays and your message flow and become more defined for you and your readers? How does gratitude for the hard knocks and the imperfections of our actions or those of others help you show up now as your best self for your kids?

Hopefully your ode to gratitude and examples of personal growth along your path for spiritual and self-fulfillment can help them feel accepted by their father and give them a good start toward their own pursuit of their best life. I consider that such a lovely gift to them.